#NephJC Chat

Tuesday, December 16th 2025, 9 pm Eastern on Bluesky

JAMA. 2025 November 7. doi: 10.1001/jama.2025.21530.Online ahead of print.

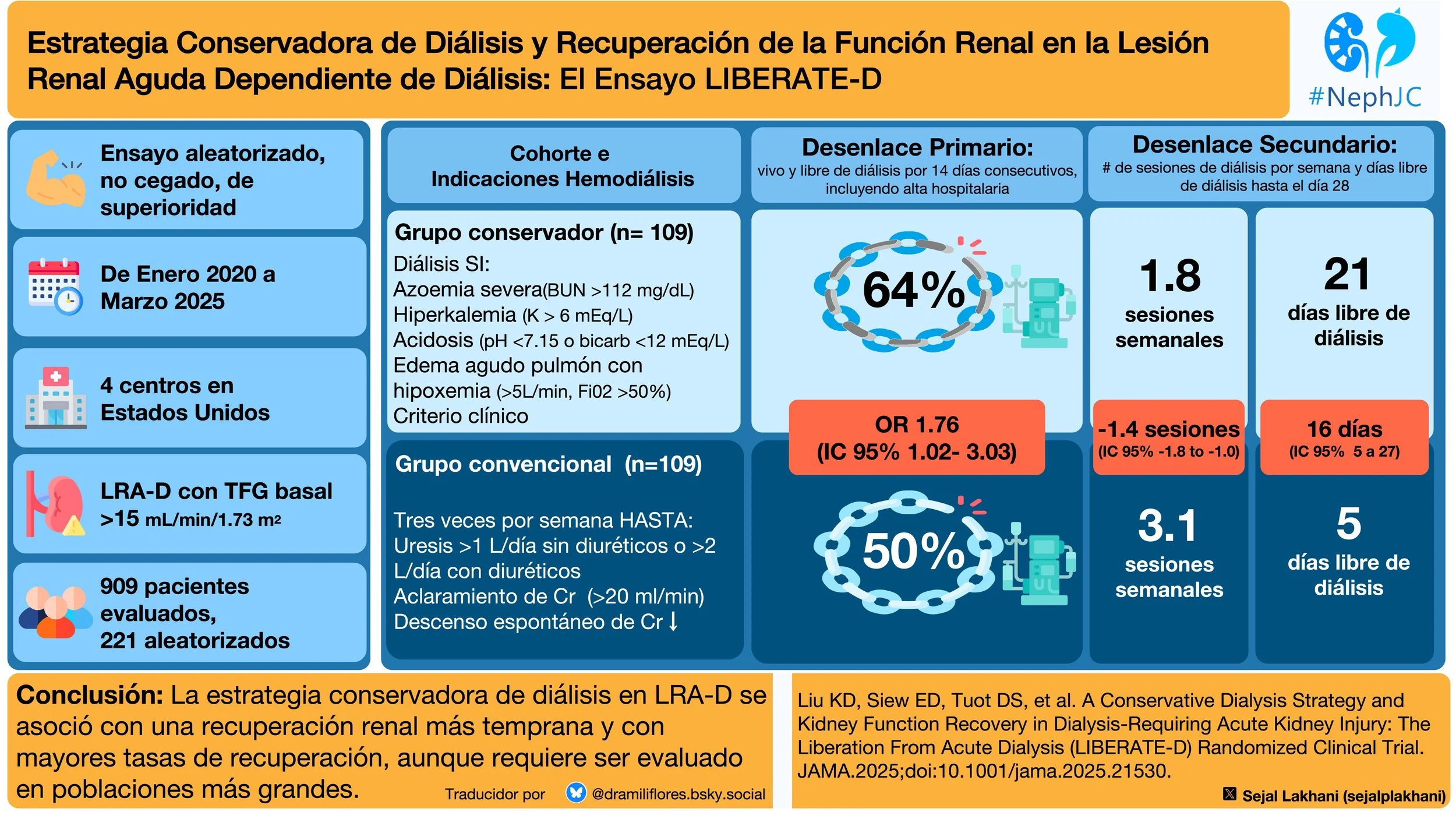

A Conservative Dialysis Strategy and Kidney Function Recovery in Dialysis-Requiring Acute Kidney Injury: The Liberation From Acute Dialysis (LIBERATE-D) Randomized Clinical Trial

Kathleen D. Liu, Edward D. Siew; Delphine S. Tuot, Anitha Vijayan; Gonzalo Matzumura Umemoto; Bethany C. Birkelo; Benjamin J. Lee; Y. Diana Kwong; Ian E. McCoy; Kevin Delucchi; Hanjing Zhuo; Chi-yuan Hsu

PMID: 41201895

Introduction

As more evidence has accumulated that early initiation of dialysis does not benefit patients, nephrologists have become more conservative with dialysis strategies. For example, multiple studies of critically ill patients have shown that “early initiation” of dialysis fails to improve mortality. (STARRT AKI Investigators, NEJM 2020 | NephJC summary; AKIKI Gaudry et al NEJM | NephJC summary ) Similarly, planned early outpatient initiation of dialysis in patients with stage V chronic kidney disease is not associated with an improvement in survival or clinical outcomes. (Cooper et al, NEJM 2010) Of course, dialysis is necessary when life-threatening complications such as severe hyperkalemia, refractory acidosis, pulmonary edema, or uremia arise. But the dialysis procedure itself carries significant risks - especially hemodynamic instability during RRT (HIRRT; Douvris et al, Int Care Med 2019), once the acute risk of death due to renal dysfunction has passed, how rapidly should we consider withdrawing dialysis and reduce hurting the kidneys even more?

Observational epidemiologic data consistently show that dialysis-requiring AKI (AKI-D) is a marker of severe illness and conveys a very high risk of death. Among patients with AKI-D, reported inpatient mortality is approximately 30–36%, 90-day mortality is 40–44%, and 1-year mortality approaches 50–54%. Only a minority of survivors are dialysis-free at 1 year, as many either die or progress to chronic dialysis dependence. (Rennie et al, Nephron 2016) At a population level, inpatient data from the United States demonstrated a sharp rise in the incidence of dialysis-requiring AKI (AKI-D) from 2000 to 2009 (average annual increase of approximately 10% accompanied by more than a doubling of associated deaths) underscoring both the growing incidence and substantial mortality burden of AKI-D. (Hsu et al, CJASN 2013)

In the most recent KDIGO guidelines from 2012 (KDIGO AKI Work Group, Kidney International 2012), it is recommended to discontinue dialysis “when it is no longer required, either because intrinsic kidney function has recovered to the point that it is adequate to meet patient needs, or because dialysis is no longer consistent with the goals of care.” There are no dialysis weaning strategies provided (evidence based, or otherwise) for AKI-D patients. The physiologic rationale for early dialysis discontinuation is grounded in how injured kidneys recover. Tubular cells are stunned, inflamed, and struggling to re-establish concentration gradients; giving the kidney some workload may provide the stimulus to restart active transport, regain concentrating ability, and ultimately recover function. Conversely, overly intensive dialysis may suppress recovery signals, expose patients to hemodynamic instability with recurrent microscopic watershed ischemic, and prolong dialysis dependence (Vijayan et al, KI Reports 2017). But typically, dialysis for the AKI-D outpatient often follows the same standard recipe as for the ESRD patient.

Should we be prescribing sequential dialysis treatments to patients only when they are absolutely necessary? Should we be aggressively attempting to discontinue dialysis at the first signs of renal recovery? This study explores whether less intensive dialysis gives the patient a better chance of being liberated from dialysis.

Methods

Study Design

LIBERATE-D was a multicenter, unblinded, 2-group parallel randomized superiority clinical trial conducted across four major US academic centers (UCSF/Zuckerberg San Francisco General, Vanderbilt, Washington University/Barnes-Jewish, and Intermountain Health). Oversight included a three-member independent data and safety monitoring board with a prespecified interim review after enrollment of 110 participants and authority to recommend stopping for safety, efficacy, or futility. The trial followed CONSORT 2025 standards.

Study Population

The trial enrolled hospitalized adults (≥18 years) with AKI requiring at least one day of dialysis, attributed at least partly to ATN, and planned for further dialysis. Participants needed to be hemodynamically stable and have a baseline eGFR ≥15 mL/min/1.73 m², as calculated by the 2009 CKD-EPI equation. In June 2021, eligibility expanded to include younger (<65 years), low-risk patients without baseline creatinine measurements. Key exclusions included mechanical ventilation, severe hypoxemia, advanced heart failure, recent long-term dialysis, or imminent transfer/discharge.

Randomization and masking

Randomization was 1:1, using a centralized computer-generated permuted block of fixed size, stratified by site and baseline eGFR (<45 vs ≥45ml/min/1.73m2). The allocation sequence was concealed from enrolling personnel. Because of the intervention, blinding after randomization was not possible. Outcome adjudication followed prespecified definitions and was performed systematically by study investigators.

Interventions

In the conservative hemodialysis group, patients only received treatment when meeting strict predefined criteria including:

severe azotemia (serum urea nitrogen >112 mg/dL)

hyperkalemia (>6 mmol/L or >5.5 mmol/L despite medical therapy)

marked metabolic acidosis (pH <7.15 or bicarbonate <12 mEq/L), or

acute pulmonary edema causing significant hypoxemia despite diuretic use (supplemental oxygen greater than 5L/min or a FiO2 >50%)

There was also permitted additional consideration for clinician judgment by the treating physician. For anuric patients, smaller increases in oxygen requirement could trigger dialysis. Patients meeting only the volume criterion were managed with ultrafiltration rather than full hemodialysis. In contrast, the conventional group received thrice-weekly hemodialysis. Dialysis treatment continued until kidney function recovered sufficiently to allow a trial of dialysis cessation, defined by urine output >1 L/day without diuretics or >2 L/day with diuretics, creatinine clearance (>20 ml/min), or spontaneous serum creatinine decline. During such dialysis withdrawal trials, dialysis was restarted if conservative criteria were met after dialysis was withheld.

In both groups final treatment decisions, including escalation to continuous hemodialysis, were made by the clinical team, with follow-up continuing to day 90. The active study intervention ended at hospital discharge.

Outcomes

The primary endpoint of the study was to evaluate kidney function recovery at hospital discharge. Recovery was defined as being alive and free from dialysis for at least 14 consecutive days, including after discharge. Notably, patients who recovered kidney function but did not survive hospitalization were not counted.

Two prespecified key secondary endpoints provided additional context on the burden and timing of hemodialysis.

The first was the number of dialysis sessions per week, which included hemodialysis, ultrafiltration, and continuous kidney replacement therapy, with continuous therapy converted into intermittent hemodialysis sessions.

The second was dialysis-free days up to day 28, a measure analogous to ventilator-free days in ICU studies, capturing both the speed of kidney recovery and the competing risk of death. Additional secondary outcomes included kidney recovery at 28 and 90 days, all-cause mortality, hospital length of stay, and time to kidney function recovery regardless of location. Safety outcomes focused on severe or clinically relevant events such as dialysis-associated hypotension, arrhythmias, cardiopulmonary arrest, urgent dialysis needs, and significant electrolyte or acid-base disturbances.

Statistical Analysis

A previous pilot trial at UCSF (RAD-AKI) suggested that limiting dialysis exposure could improve kidney recovery: 67% of patients in the conservative group recovered kidney function by discharge compared with just 40% in the thrice-weekly hemodialysis group. The LIBERATE-D trial planned enrollment of 220 participants, providing 80% power to detect a prespecified, clinically relevant 20% absolute difference in recovery rates between groups.

Statistical analyses were prespecified and conducted using an intention-to-treat approach. Non-normally distributed continuous variables were analyzed with nonparametric tests, categorical outcomes with χ² or Fisher exact tests, and between-group differences estimated directly with appropriate confidence intervals. The primary outcome was further evaluated using multivariable logistic regression adjusting for key baseline characteristics. A two-sided α of 0.05 defined statistical significance.

Funding

Funding was provided by federal grants from the NIH/NIDDK.

Results

The trial randomized 220 adults with AKI-D, from January 2020 to March 2025. After censoring one participant in each group for transplant or withdrawal, 218 contributed to the primary outcome analysis.

Figure 1. Flow of participants in the LIBERATE-D trial, from Liu et al, JAMA 2025

Baseline characteristics

The mean age was 56 years, 67% male, with about 60% White, 13% Black, and 9% Asian. Most cases of AKI-D were driven by ischemia, nephrotoxin exposure, sepsis, or postoperative complications. Most patients were admitted by medicine service (65%), and 80% were randomized prior to ICU admission. One-third of participants had diabetes, and 15% remained on vasopressors two days after randomization. Baseline kidney function and dialysis exposure before randomization were similar between the conservative and conventional dialysis groups.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics, from Liu et al, JAMA 2025

Primary End Point

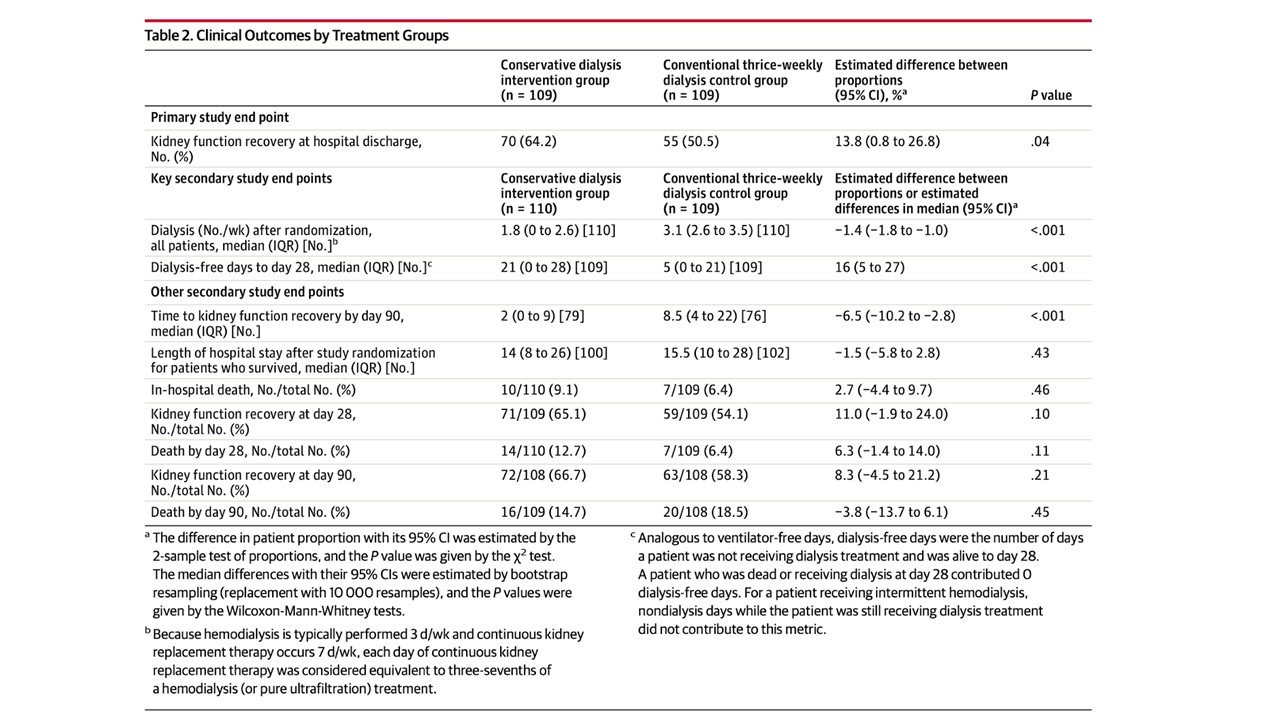

At hospital discharge, kidney function recovery was achieved in 64% of patients in the conservative dialysis group compared with 50% in the conventional group – a 13.8% absolute difference (unadjusted OR, 1.76; 95% CI, 1.02–3.03).

Table 2. Clinical outcome by treatment groups, from Liu et al, JAMA 2025

However, after adjusting for age, sex, race, ethnicity, and baseline eGFR, the difference was attenuated and not statistically significant (adjusted OR, 1.56; 95% CI, 0.86–2.84).

eTable 2. Multivariable logistic regression analysis for kidney recovery from Liu et al, JAMA 2025

Key Secondary End Points

Dialysis frequency

Patients in the conservative group received fewer dialysis treatments (median 1.8 vs 3.1 sessions/week; difference -1.4 sessions/week; 95% CI -1.8 to -1.0). Overall, 65.5% of patients in the conservative group received dialysis after randomization, compared with 91.8% in the conventional group. In the conservative arm, the most common trigger for dialysis was clinician judgment, related to perceived volume overload or uremia.

Time-to-recovery analyses

Patients managed with the conservative strategy experienced substantially more dialysis-free days by day 28 (median 21 vs 5 days), corresponding to a 16-day difference favoring conservative dialysis. As shown on figure 2, separation between groups emerged early, with the most pronounced divergence within the first 10-12 days, though the difference at 28 days was not significant (p = 0.10).

Figure 2. Time to first kidney recovery from Liu et al, JAMA 2025

Other secondary outcomes and safety signals

Despite the early recovery in the conservative group, rates of kidney recovery at days 28 and 90 converged. There were no differences for in-hospital mortality (9.1% vs 6.4%) and though there were twice as many deaths in the conservative group at 28 days (14 versus 7) the numbers were similar at 90 days. Median hospital length of stay after randomization was also similar (14 vs 15.5 days).

Process-of-care findings

Triggers for dialysis in the conservative arm: Almost half (46%) of treatments were initiated for clinician judgement, mainly due to perceived volume or uremic symptoms. Furthermore, serum urea nitrogen > 112 mg/dl accounted for 36% of triggers, hyperkalemia 13%, and hypoxemia for 8%.

eTable 5. Triggers for dialysis sessions in the conservative group, from Liu et al, JAMA 2025

Safety

Serious adverse events were uncommon and predominantly unrelated to the intervention. Dialysis-associated hypotension was less frequent with the conservative strategy, despite slightly higher ultrafiltration rates.

Table 3. Serious adverse events by groups from Liu et al, JAMA 2025

Discussion

Conservative management once again breaks the mold in dialysis. In patients with AKI-D, more dialysis isn’t necessarily better. Adopting later starts and fewer sessions seems to be the new mantra in AKI-D patients (LIFO= last in, first out). The LIBERATE-D trial tested a conservative, criteria-driven dialysis strategy in which hemodialysis or ultrafiltration was performed only when specific metabolic or clinical criteria were met. The results were notable: patients in the conservative group not only had higher rates of kidney recovery at hospital discharge, but also experienced fewer dialysis sessions, more dialysis-free days, fewer dialysis-associated hypotension events, and no increase in serious adverse events. In other words, carefully selecting when to dialyze helped kidneys recover faster while reducing treatment burden.

It is interesting to note that during randomization nearly 400 patients were excluded due to “the clinical team declining enrollment”. Dialyzing patients with AKI three times a week, in general, is less demanding because it requires less attention to metabolic and volume derangements that will be corrected with the next dialysis treatment in rapid, pre-ordered succession. Using a more conservative approach to dialysis requires daily bedside evaluations of patients, and labwork, to make informed decisions. Allowing for significant metabolic derangements may be uncomfortable to clinicians who consider AKI-D patients to be fragile, as noted above by their very high mortality risk. However, for too long hemodialysis continuation, after initiating for life threatening metabolic or volume derangement, has followed a largely cookie-cutter approach (borrowed from ESRD care) despite the fact that AKI-D represents a fundamentally different population with renal recovery potential. Nephrologists may have to step out of our comfort zone, and alter long held dogma, to improve patient outcomes.

This study fills a critical gap in AKI-D research. Over the past two decades, most trials focused on dialysis modality, dose, or timing but few had examined how to wean patients off dialysis. A recent systematic review on weaning from RRT in critically ill AKI-D patients concluded that most of the available data comes from observational studies, and was of limited clinical value (Klouche et al, J Clin Med 2024).

A decision algorithm for weaning from RRT from Klouche et al, J Clin Med 2024

Until now, no intervention had proven capable of improving kidney recovery in AKI-D. An ongoing pilot Canadian trial is examining adjustment of dialysate temperature, sodium, calcium and UF rates to promote recovery. LIBERATE-D provides large-scale, randomized evidence that a selective, criteria-driven decision tool can decrease dialysis exposure and improve outcomes. Interestingly, these findings align with a previous analysis suggesting that less frequent dialysis may actually speed renal recovery (Vijayan et al, KI Reports 2017). The reduced number of dialysis-associated hypotension events in the conservative group offers a potential explanation: dialysis itself, if applied too aggressively may hinder kidney recovery.

Guidelines provide a framework for care, but treatment should always be individualized. Considering factors such as illness severity, residual kidney function, metabolic demands, and the patient’s overall recovery potential may improve outcomes by minimizing dialysis exposure. Participants in LIBERATE-D were generally less critically ill (none required mechanical ventilation, and many retained native kidney clearance). Thus, this framework may not be as helpful in decision making for AKI-D patients in the ICU setting. The study’s strengths include clear separation in dialysis frequency, very few missing data points, recovery rates in the control group that matched power calculations, and enrollment across multiple centers, enhancing generalizability.

Key limitations are the lack of blinding (though outcomes were objective), a short median intervention duration (15 days), small baseline imbalances, and a limited sample size that attenuated the effect and widened confidence intervals. Generalizability may be limited by significant use of “clinical judgement” in dialysis decisions, and the varying discomfort nephrologists feel when keeping patients' lab data well outside euboxic parameters. While differences in kidney recovery were observed at discharge (13.8%) they did not persist through day 90 (p = 0.21) suggesting that the conservative strategy may hasten recovery, but not necessarily increase the overall recovery rate. In hospital mortality was numerically higher (double) in the conservative strategy, in a closely monitored clinical trial setting. This underscores that translating this into the real world, where close monitoring with a conservative strategy may not be practical, could be fraught with serious consequences. These findings highlight the need for larger trials, potentially extending into the outpatient setting, to fully assess conservative dialysis strategies.

Conclusion

LIBERATE-D provides compelling evidence that targeted, individualized dialysis in AKI-D can optimize patient recovery from dialysis. By delivering therapy only when indicated, the study demonstrated reductions in treatment burden and dialysis-associated complications, alongside accelerated kidney recovery.

Summary prepared by

Marc Lawrence Soco

Consultant Nephrologist

Chong Hua Hospital, Cebu, Philippines

Sejal Lakhani

Internal Medicine Resident

Lehigh Valley Health Network, Allentown, PA

Reviewed by

Cristina Popa, Brian Rifkin, Milagros Flores,

Jade Teakell, Swapnil Hiremath

Header Image created by AI, based on prompts by Janany S