#NephJC Chat

Tuesday, Feb 6, 2018, 9 pm Eastern

Wednesday, Feb 7, 2018, 8 pm GMT, 12 noon Pacific

JAMA. 2018 Jan 2;319(1):49-61. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.19152.

Association of Race and Ethnicity With Live Donor Kidney Transplantation in the United States From 1995 to 2014.

Purnell TS, Luo X, Cooper LA, Massie AB, Kucirka LM, Henderson ML1, Gordon EJ, Crews DC, Boulware LE, Segev DL

PMID: 29297077

Related Editorial in JAMA by Jay and Cigarroa

A Parallel 2017 article with data from the UK:

Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2017 May 1;32(5):890-900. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfx036.

Barriers to living donor kidney transplantation in the United Kingdom: a national observational study.

Wu DA, Robb ML, Watson CJE, Forsythe JLR, Tomson CRV4, Cairns J5, Roderick P, Johnson RJ, Ravanan R, Fogarty D, Bradley C, Gibbons A, Metcalfe W, Draper H, Bradley AJ, Oniscu GC.

PMID 28379431 (full text free at NDT)

Introduction

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is a growing public health threat in the United States (US), with a disproportionate burden in racial and ethnic minorities. Hypertension and diabetes, the two most common causes of chronic kidney disease, are becoming more common in the general population. The patients developing kidney failure is also changing. Today's CKD patient is older, more likely to be a racial and ethnic minority of with lower socioeconomic status. In addition to the increase in diabetes and hypertension, there is more obesity. With the growth in CKD there is increasing need for living kidney donors. The number of patients waitlisted for transplantation far exceeds the number of donated organs, and wait times can exceed 5 years in some regions of the country. With increasing prevalence of both kidney failure and earlier stages of CKD these trends are likely to continue.

Fig 6.15a from USRDS 2017, showing total live donor transplant numbers by race

Fig 6.15b from USRDS 2017, showing total live donor transplant rates by race

Live donor kidney transplantation (LDKT) accounts for one-third of kidney transplants performed in the United States and continues to offer superior outcomes compared to maintenance dialysis and deceased donor kidney transplantation for individuals with end-stage kidney disease (ESRD). LDKT allows transplant recipients to bypass the deceased donor kidney transplant waiting list and improve rapid access to transplantation.

In the United States, racial-ethnic minorities experience disproportionately high rates of ESRD but are far less likely to undergo kidney transplantation. Purnell and colleagues in another paper, identified and characterized the barriers to LDKT. These barriers to LDKT include:

Recipient and donor attitudes and beliefs towards transplantation

Clinical characteristics of the donor and recipient

Health care provider knowledge, attitudes and behaviors

Population awareness, attitudes, and disease burden.

Multilevel Influences Contributing to Barriers to Living Kidney Donation for Racial-Ethnic Minorities at Each Stage of the LDKT Process

Figure from Purnell et al. Adv in CKD, 2012

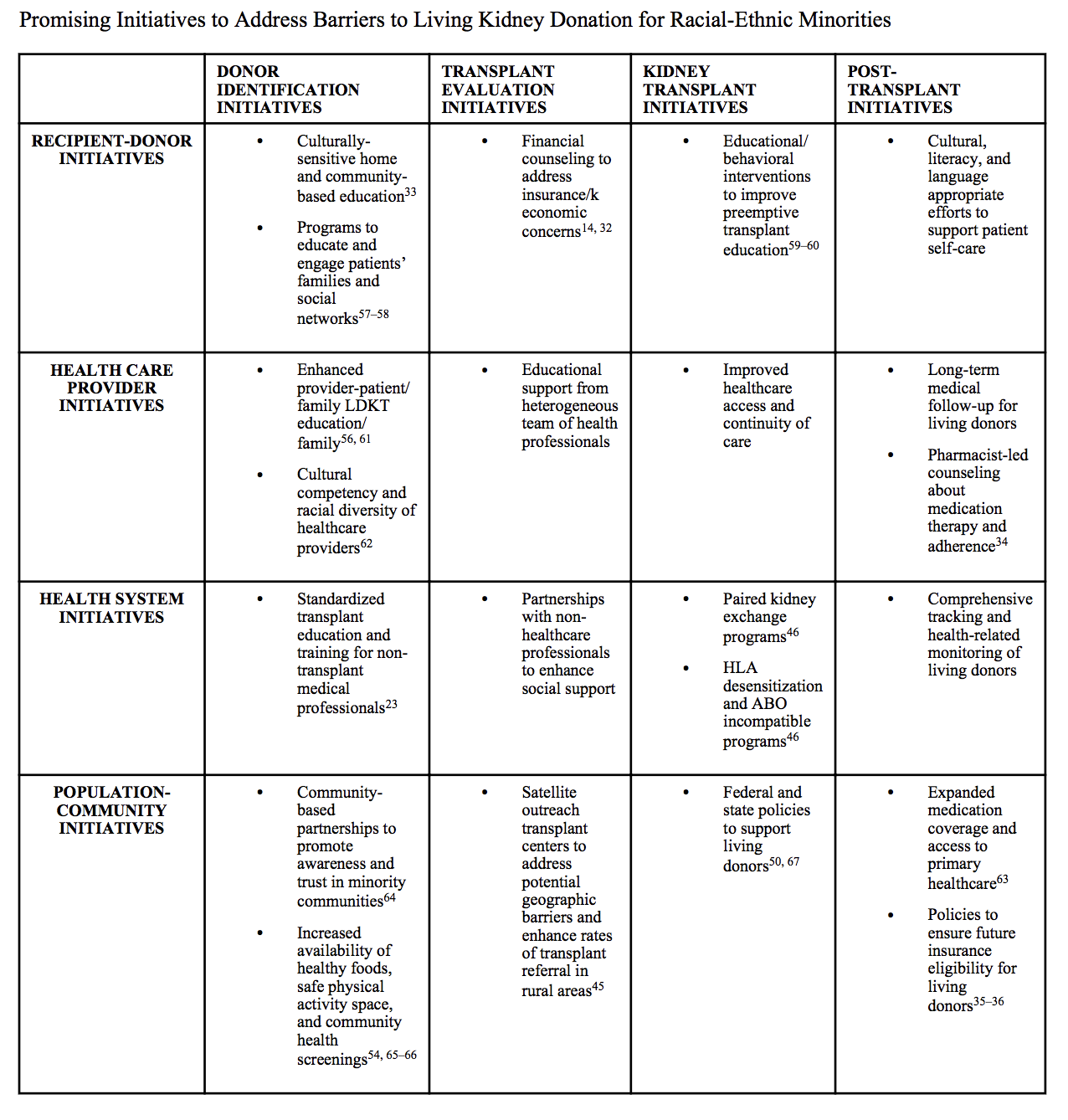

A number of promising strategies to address barriers to living kidney donation at each stage of LDKT process currently exist.

Table from Purnell et al. Adv in CKD, 2012

Over the past 2 decades, there has been increased attention and effort to reduce disparities in LDKT for black, Hispanic, and Asian patients with end-stage kidney disease. How many of these are related to the system and how many are related to the patient? Check out the NephMadness discussion on this issue from 2017.

The goal of this present study was to investigate whether these efforts have been successful.

Methods

A secondary analysis of a prospectively maintained cohort study conducted in the US of 453 ,162 adult first-time kidney transplantation candidates, with patients grouped by 4 fixed categories:

white

black/African American

Hispanic/Latino

Asian

In the entire cohort, mean age was 50.9 years; 39% were women; 48% were white; 30%, black; 16%, Hispanic; and 6%, Asian - all included in the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients (SRTR) between January 1, 1995, and December 31, 2014, with follow-up through December 31, 2016.

Outcomes

The primary study outcome was time to LDKT.

Multivariable Cox proportional hazards and competing risk models were constructed to assess changes in racial/ethnic disparities in LDKT among adults on the deceased donor kidney transplantation waiting list and interaction terms were used to test the statistical significance of temporal changes in racial/ethnic differences in receipt of LDKT. Data were categorized into 5-year increments:

1995-1999

2000-2004

2005-2009

2010-2014

Study participants were censored due to the following reasons:

Death (n = 30, 653)

Deceased donor kidney transplantation (n = 86, 008)

Waiting list removal due to reasons other than receipt of kidney transplantation or death (n = 50, 748)

Two years after initial listing (n = 226 ,237).

Results

Population Characteristics

Overall, there were 39,509 LDKTs among white patients, 8,926 among black patients, 8,357 among Hispanic patients, and 2,724 among Asian patients.

Table 1 from Purnell et al, JAMA 2018

Table 2 from Purnell et al JAMA, 2018

From Table 1 and 2 above: Mean age, body mass index, and prevalence of end-stage kidney disease secondary to diabetes increased from 1995 to 2014. The prevalence of end-stage kidney disease due to hypertension or diabetes was highest among black and Hispanic patients, whereas the prevalence of end-stage kidney disease due to glomerular diseases or other causes was highest among white and Asian patients.

Black and Hispanic patients were younger and also less likely to have college degrees than Asian and white patients. The prevalence of private health insurance was highest among white and Asian patients, and the prevalence of Medicare as the primary coverage was highest among black and Hispanic patients. Black and Hispanic patients spent the longest time receiving dialysis.

Figure 1 from Purnell et al JAMA 2018

Temporal Changes in Receipt of Live Donor Kidney Transplantation by Candidate Race/Ethnicity

Figure 1A: In 1995, the cumulative incidence of live donor kidney transplantation at 2 years after placement on the deceased donor kidney transplantation waiting list was:

7.0% among white patients

3.4% among black patients

6.8% among Hispanic patients

5.1% among Asian patients

In 2014, the cumulative incidence of live donor kidney transplantation at 2 years after placement on the deceased donor kidney transplantation waiting list was:

11.4% among white patients

2.9% among black patients

5.9% among Hispanic patients

5.6% among Asian patients

The graphs illustrate the Kaplan-Meier estimated cumulative incidence at 2 years of being on the waiting list among kidney transplantation candidates.

Table 3: The proportional incidence of live donor kidney transplantation among black and Hispanic patients was lower when comparing the rates in 1995-1999 vs. 2010-2014. However, live donor kidney transplantation has not declined for these groups in terms of absolute numbers compared with the initial period studied. The greatest period of growth occurred from 1995 to 2009, the volume of live donor kidney transplantation more than doubled for every racial/ethnic group. The largest increases in live donor kidney transplantation were among Hispanic and Asian recipients, which increased nearly three-fold.

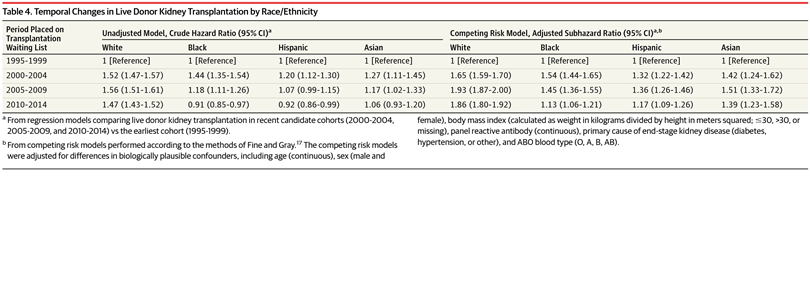

Table 4: adjusted subhazard ratio for the receipt of live donor kidney transplantation in the 2010-2014 cohort was 1.86 (95% CI, 1.80-1.92) among white patients, 1.13 (95% CI, 1.06-1.21) among black patients, 1.17 (95% CI, 1.09-1.26) among Hispanic patients, and 1.39 (95% CI, 1.23-1.58) among Asian patients.

Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Receipt of Live Donor Kidney Transplantation From 1995-1999 to 2010-2014

Table 5: In 1995-1999, compared with receipt of LDKT among white patients, the adjusted subhazard ratio was 0.45 (95% CI, 0.42-0.48) among black patients, 0.83 (95% CI, 0.77-0.88) among Hispanic patients, and 0.56 (95% CI, 0.50-0.63) among Asian patients. In 2010-2014, compared with receipt of LDKT among white patients, the adjusted subhazard ratio was 0.27 (95% CI, 0.26-0.28) among black patients, 0.52 (95% CI, 0.50-0.54) among Hispanic patients, and 0.42 (95% CI, 0.39-0.45) among Asian patients.

An estimated adjusted subhazard ratio of greater than 1 suggests that the racial/ethnic group is more likely to receive live donor kidney transplantation compared with white candidates.

Potential Mechanisms Influencing Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Receipt of Live Donor Kidney Transplantation

Figure 2: even in fully adjusted models, live donor kidney transplantation disparities substantially increased over time for black and Hispanic patients.

Supplement eTable 2. Sensitivity analysis: models stratified by age categories, neighborhood poverty, education, and health insurance type show that the magnitude of the increase over time in racial/ethnic disparities in the receipt of live donor kidney transplantation was greater for black patients and hispanic patients living in poorer neighborhoods, without a college degree, and with Medicare insurance.

Characteristics of Live Donor Kidney Transplantation Recipients and Donors From 1995-1999 to 2010-2014

From Supplement eTable 6: across all racial/ethnic groups, live donor kidney transplantation recipients in 2010-2014 were more likely to be older, male, have a college degree, and receive preemptive live donor kidney transplantation than those in 1995-1999.

Donors of live donor kidney transplantation in 2010-2014 were more likely to be older or female, and less likely to be biologically related or concordant by race/ethnicity with the recipient compared with donors of live donor kidney transplantation from 1995-1999.

Conclusion

Among adult first-time kidney transplantation candidates in the United States who were added to the deceased donor kidney transplantation waiting list between 1995 and 2014, disparities in the receipt of live donor kidney transplantation increased from 1995-1999 to 2010-2014. The racial/ethnic differences in health care access and socioeconomic status factors may be related to the increasing racial/ethnic disparities in the receipt of live donor kidney transplantation among black and Hispanic patients. The study findings suggest that current efforts to reduce live donor kidney transplantation disparities need to be revisited, perhaps with a national strategy initiative.

Limitations

The authors acknowledge that the study had limitations:

some potential for misclassification bias, since the variables (race/ethnicity and comorbidities) available in the SRTR are clinician-reported

inability to further subcategorize the broad racial/ethnic categories available in the registry.

inability to assess the extent to which potential racial/ethnic differences in preferences about and willingness to pursue live donor kidney transplantation among kidney transplantation candidates

inability to account for individual-level patient income