“A bear, however hard he tries, grows tubby without exercise.”

― Winnie-the-Pooh

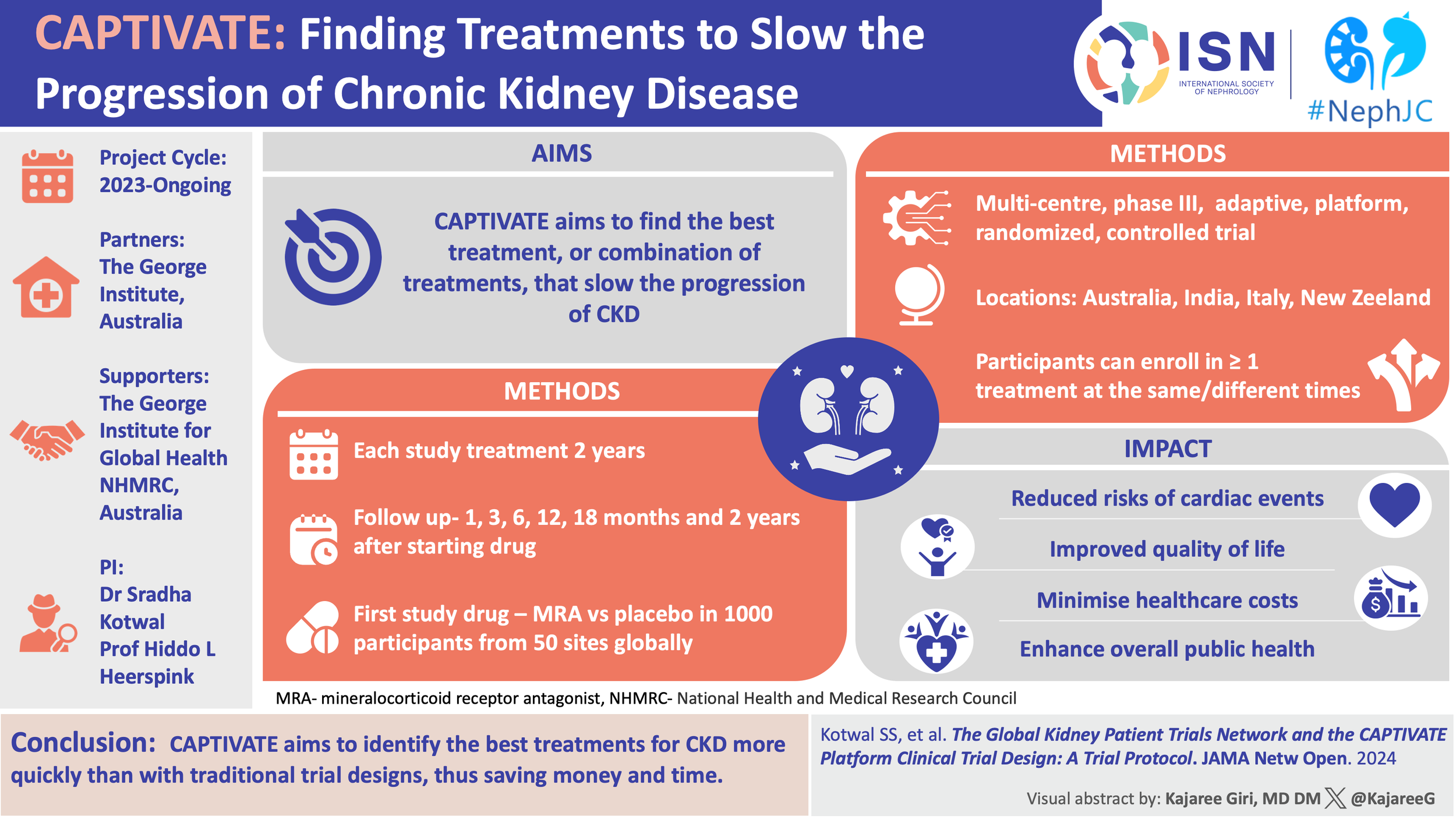

Next NephJC: The CKD Classification System in the Precision Medicine Era

HARMONY: Is it safe to withdraw steroids early after Kidney Transplant?

Does Contrast cause acute Kidney Injury?

Iodinated contrast is well known to cause acute kidney injury (AKI), mainly from its physico-chemical properties, and is the commonly cited as being the third most common cause of AKI in hospitalized patients. But is this really true? Even the term contrast-induced AKI (CI-AKI) is now being increasingly replaced by contrast-associated AKI (CA-AKI), and could contrast be an 'innocent bystander'?

Do Crescents matter for IgA Nephropathy?

Could it be that Simple: A Vitamin to Protect the Kidney?

Need a Kidney? There's an App for that

Fistula Failure: Can Anesthesia Solve our Vexing Vascular Access Problems?

Red Meat: What is it good for?

NINJA: A systematic approach to reduce exposure to nephrotoxins

#NephJC Book Club: the wrap up #PWSYN

Assigning causality in AKI – Untying the Gordian Knot?

EMPA-REG Renal results.

#NephJC posts on #EXTRIP now live at @Ukidney

The #EXTRIP blog posts by the NephJC team are live at Ukidney and a summary of the chat about the intoxications.

Acute kidney injury, when to dialyze

Acetazolamide for metabolic alkalosis in ventilated patients

#NephJC this Tuesday, Jan 12 and Wednesday, Jan 13: SPLIT trial

We are going deep on this landmark RCT of saline versus balanced solutions.

JAMA has made the article open access for NephJC. Follow this link. JAMA is also going to offer prizes for the best tweet from the Jan 12th and Jan 13th discussions so warm up those twitter clients!

Spironolactone primer

Resistant hypertension is an important clinical problem. It is commonly defined as inadequate blood pressure control despite use of three antihypertensive agents of different classes at optimal dosages; one of the three should be an appropriately dosed diuretic. About 10-15% of hypertensive patients have resistant hypertension.

The magical powers of aldosterone antagonists first started to be publicized in the late 90's and in 2003 Calhoun showed a dramatic effect among patients with resistant hypertension:

“A total number of 76 subjects were included in the analysis, 34 of whom had biochemical primary aldosteronism. Low-dose spironolactone was associated with an additional mean decrease in BP of 21 ± 21 over 10 ± 14 mm Hg at 6 weeks and 25 ± 20 over 12 ± 12 mm Hg at 6-month follow-up. The BP reduction was similar in subjects with and without primary aldosteronism and was additive to the use of ACE inhibitors, ARBs, and diuretics.”

This was backed up by additional observational data as part of the ASCOT trial experience. The investigators found dramatic efficacy from modest doses of spironolactone among the 1,411 patients that received spironolactone as a fourth line agent:

“During spironolactone therapy, mean blood pressure fell from 156.9/85.3 mm Hg (SD: ±18.0/11.5 mm Hg) by 21.9/9.5 mm Hg (95% CI: 20.8 to 23.0/9.0 to 10.1 mm Hg; P<0.001); the BP reduction was largely unaffected by age, sex, smoking, and diabetic status. ”

The first randomized, placebo controlled trial in resistant hypertension was published in 2011. The ASPIRANT trial (PDF) showed a more modest, but still clinically significant reduction blood pressure.

An important caution when looking at spironolactone data is that it appears that black patients are more sensitive to increases in aldosterone, so one could predict more modest blood pressure improvements with spironolactone in a European population. See Tu et al. (Full text).

Another critical aspect of resistant hypertension is addressing non-adherence.

“A mass spectrometry urine toxicology screening of antihypertensive drugs reported that 53% of patients with resistant hypertension were non-adherent to treatment. Of these, 70% were incompletely adherent and 30% were completely non-adherent. Reduced adherence was not attributed to a particular antihypertensive class. Another urine analysis study found that 23% of patients referred for renal denervation were completely non- adherent to their prescribed antihypertensive treatment.”

This is why PATHWAY-2's attempt to measure minimize non-adherence is so important.

This week's chat on PATHWAY-2 represents the first randomized controlled trial against an active control group. The fact that aldosterone rises above other fourth line agents to provide meaningful advantages in the treatment of resistant hypertension is important.

We are coming to a new age in hypertension management. On November 9, at 2:00 PM at the AHA meeting in Orlando the SPRINT Trial results will be released. This will almost certainly result in a wave of more aggressive blood pressure control. Almost simultaneously we now have access to the first of the next generation potassium binders, patiromer. This brings the hope of avoiding the most frightening of the side effects from aldosterone antagonists, hyperkalemia. These three seemingly unrelated events are going to be major influences on the treatment of hypertension going forward.

The IV versus PO iron conundrum for Tuesday and Wednesday

Joel said he would write the summary. Suzanne said she would write the summary and in the end wires got crossed and they both wrote the summary. Sigh. We are ardent conservationists and strongly believe that no part of the buffalo should go to waste so here is Dr. Norby's summary of this week's NephJC article:

A randomized trial of intravenous and oral iron in chronic kidney disease

Rajiv Agarwal, John W Kusek, and Maria K Pappas

Kidney International advance online publication 17 June 2015

doi: 10.1038/ki.2015.163

BACKGROUND

Anemia is common in patient with stages 3-5 chronic kidney disease (CKD) due to decreased erythropoietin production as well as iron deficiency, including the functional iron deficiency that can develop while using erythropoiesis-stimulating agents (ESA).

The KDIGO Clinical Practice Guideline for Anemia in CKD recommends (grade 2C) the use of IV iron in adult patients with CKD note yet on dialysis if 1) an increase in hemoglobin level is desired to avoid or minimize blood transfusions and ESA use and/or to alleviate symptoms potentially related to anemia and 2) TSAT is ≤30% and ferritin is ≤500 ng/ml. The Guideline also states that a 1-3 month trial of oral iron may be considered for patients not yet on dialysis.

Safety and risks of IV iron use in the non-dialysis CKD population are not fully understood although an author of the current study, Agarwal, along with other colleagues previously demonstrated that IV iron use can lead to increased oxidative stress, endothelial damage, and even renal injury.

The hypothesis of the current study, REVOKE (randomized trial to evaluate intravenous and oral iron in chronic kidney disease), was that IV iron would result in greater decrease in kidney function compared with oral iron in iron-deficient patients with moderate to severe CKD not yet on dialysis.

METHODS

Design: open-label, parallel-group, active-control, single-center randomized trial

Setting: A safety-net hospital and a VA Hospital, both in Indianapolis, IN; August 2008 – November 2014.

Inclusion criteria:

- ≥18 years old

- eGFR 21-60 ml/min/1.73 m2, not on dialysis

- Hemoglobin <12 g/dl

- Serum ferritin <100 ng/ml or serum transferring saturation <25%

Exclusion criteria:

- Pregnant or breast feeding females

- Known hypersensitivity to any intravenous iron, iothalamate meglumine (Conray 60, Malinckrodt) or iodine

- Severe anemia that required imminent red blood cell (RBC) transfusion (Hgb <8 g/dL) or the potential need for imminent RBC transfusion (e.g., active bleeding)

- Persons with acute kidney injury

- History of intravenous iron use within the month prior to screening

- Iron overload (serum ferritin >800 ng/nl or transferrin saturation >50%)

- Anemia not caused by iron deficiency (e.g., sickle cell anemia)

- History of surgery or systemic or urinary tract infection within the past month

- Organ transplant recipients

- Persons currently being treated with immunosuppressive agents

Randomization and Blinding: 1:1 ratio, using computer generated permuted blocks, randomized to either oral iron or IV iron using concealed opaque envelopes

Primary outcome:

- Difference between treatment groups in slope of mGFR decline from baseline to 2 years adjusted for the log of baseline urinary protein/creatinine ratio compared with baseline at 8 weeks, 6 months, 12 months, and 24 months after randomization.

Secondary outcomes:

- further adjustment of the primary outcome for age, sex, race (Black vs. non-Black), angiotensin-converting enzyme/angiotensin receptor blocker use, and the presence or absence of cardiovascular disease (all determined at baseline)

- between-group % change in proteinuria from baseline to 8 weeks

- difference between hemoglobin response between treatment groups

- change in KDQOL

Statistical analysis:

- Intention-to-treat, if the participant received at least one dose of study medication

- Linear mixed model with GFR as outcome variable

- Assumptions: mean rate of decline in GFR of 4 ml/min per 1.73 m2 per year in the oral iron group and a 50% greater decline in the IV iron group and a cumulative rate of dropout of 25%

- Recruitment target of 100 patients for each treatment group with a minimum duration of follow-up of 2 years to achieve 82% power to detect hypothesized difference in decline in kidney function at the 5% level of significance

- 2-sided t-test considered significant for p<0.05

INTERVENTION

Participants were treated over 8 weeks beginning at the time of randomization. Those randomized to the IV iron group received iron sucrose 200 mg IV over 2 h at weeks 0, 2, 4, 6, and 8. Participants randomized to oral iron were counseled to take ferrous sulfate 325 mg three times daily for 8 weeks.

RESULTS

Trial was terminated early due to higher serious adverse event rate in IV iron group (199 per 100 patient years) compared with oral iron group (168.4 per 100 patient years); adjusted incidence rate ratio 1.60 (1.28–2.00), P<0.0001. Statistically significant increases in infections and cardiovascular events were observed. In particular, the incidence of lung and skin infections was increased 3-4x and of hospitalization for heart failure was increased 2x in the IV iron group after adjusting for the more favorable baseline characteristics in that group.

Decrease in mGFR between groups was similar between both groups, -3.6 ml/min per 1.73 m2 per year for oral iron group and -4 ml/min per 1.73 m2 per year for IV iron group.

Hemoglobin increase, change in proteinuria over time, ESA use, and need for blood transfusions were not significantly different in the 2 groups. KDQOL domain scores did not change over time in either group.

DISCUSSION

Since this study was limited to patients with stage 3-4 CKD not yet on dialysis, results cannot be generalized to patients already on dialysis.

The primary outcome of comparing decline in mGFR between groups could not be evaluated due to early termination of the study due to safety concerns related to increased risk of infection and cardiovascular events. While additional studies evaluating the long-term safety of IV iron use in this population are necessary, should the oral route be preferred when initiating iron supplementation in patients with stage 3-4 CKD? Moreover, based on the time course of hemoglobin increase in patients in the oral iron group of this study, it would seem reasonable that a trial of oral iron be given to patients with CKD not yet on dialysis for a full 3 months, rather than at least 1 month and up to 3 months as suggested in the KDOQI guidelines.

Being Mortal: Chapter Seven

I did not like the Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks. I thought the story of the HeLa cells and the story of Ms Lacks and her family was interesting and introduced me to a history of medicine that had previously been invisible. The story was fascinating but the book fell flat because of the way that the author, Rebecca Skloot, inserted herself into the story. Every chapter that was told from Ms. Skloot's point of view came across as having low stakes and was generally uninteresting. I finished the book with the belief that this point-of-view writing was a poor technique for non-fiction.

I was wrong. While it didn't work for the Immortal Life, Dr. Gawande uses it to dramatic effect in Being Mortal. Gawande is a recuring character in the book and the previous chapters we are taken on his journey from a doctor with conventional western medicine understanding about dying o a much deeper and richer understanding. In chapter seven, however, Gawande changes from a researcher to an active participant as his dad suffers a devastating illness and he needs to put his new found knowledge of hospice, assisted living, palliative care and end-of-life decisions to use.

“The scan revealed a tumor growing inside his spinal cord.

That was the moment when we stepped through the looking glass. Nothing about my father’s life and expectations for it would remain the same. Our family was embarking on its own confrontation with the reality of mortality. The test for us as parents and children would be whether we could make the path go any differently for my dad than I, as a doctor, had made it go for my patients. The No. 2 pencils had been handed out. The timer had been started. But we had not even registered that the test had begun.”

In 2006, Gawande's father, Dr. Atmaram Gawande, went for an MRI to diagnose a slowly progressive pain in his neck associated with numbness in his left hand. The scan revealed a spinal cord tumor.

The Gawande's then consulted a pair of neurosurgeons, one in Boston and one at the Cleveland Clinic. Gawande explains the bedside manner of both doctors by describing a paper by the medical ethicists Linda and Ezekiel Emmanuel that described the three type of relationships doctors could have with patients:

- Paternalistic

- Informative

- Interpretive

Gawande describes all three types. The first is the doctor we read about from the 50's. The all knowing God-like figure that tells the patients what they should do and does not discuss options that the doctor does not think are optimal. We would like to think that we are past this but in reality it is more common than we care to admit.

The second type, informative, is the opposite of the paternalistic relationship. The doctor informs the patient of the facts and figures needed to figure out the best option and then lets the patient make the decision. Gawked explains that this works best for for simple issues with clear choices and straightforward trade-offs. The more complex and emotional the issue the more this method breaks down.

The Emmanuels third option, interpretive, is a hybrid of the two earlier models. “Here the doctor’s role is to help patients determine what they want. Interpretive doctors ask, “What is most important to you? What are your worries?” Then, when they know your answers, they tell you about the red pill and the blue pill and which one would most help you achieve your priorities.”

The chapter winds its way through his father's illness and we see Gawande struggle to use the lessons he has learned to help his father. They make some excellent decisions, they make some mistakes, they meet some excellent physicians and some clunkers. The face decisions on hospice, medical decision making and hospice. Despite some missteps, by the end of the chapter his father is in hospice and living a surprisingly full life.

“But walking slowly, his feet shuffling, he went the length of a basketball floor and then up a flight of twenty concrete steps to join the families in the stands. I was almost overcome just witnessing it. Here is what a different kind of care—a different kind of medicine—makes possible, I thought to myself. Here is what having a hard conversation can do.”