Preamble

As COVID-19 changes how we look at everything in medicine, one population stands out, patients on dialysis. Of all the patients who engage with health system, patients on dialysis may have the most frequent and the most intimate contact with the medical system. Additionally, these patients can’t abide by the standard instructions to avoid infection, i.e. they are unable to just shelter in place for a week or two while the epidemic burns itself out. Because of this, we need a special fund of knowledge to make sure these patients remain as safe as possible. What follows is a summary and discussion of some of the major issues and challenges facing dialysis patients during the COVID-19 Pandemic. We are trying to collate the facts - and these are not recommendations in any way because the evidence is either too sparse or rapidly evolving. There are also logistical challenges or local institutional policies or constraints that one should keep into account while reading what follows. We will also discuss the emerging use of telemedicine for CKD clinics.

A few words about the state of SARS-CoV2 science

Before we start reviewing the literature it is important to recognize the current landscape of peer review (or lack thereof). Especially in the fast moving world of COVID-19 research. Brian Byrd provides a nice overview for our readers here. The differences between preprints, letters to editor, rapid response and other publication types are discussed detail there.

Curated and Edited by

Swapnil Hiremath, MD, MPH, University of Ottawa, Canada

Joel Topf, MD, FACP Oakland University William Beaumont School of Medicine, Rochester, MI

Contributors

Graham Abra, MD Stanford University and Satellite Healthcare, San Jose, CA

Neiha Arora, Kaiser Permanente Northern California, Fremont, CA Manasi Bapat, MD East Bay Nephrology Medical Group, Berkeley, CA

Divya Bajpai, MD, KEM Hospital, Mumbai, India Todd Bruno, Kaiser Permanente Northern California, Vacaville, CA Anna M. Burgner, MD, MEHP Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN Gates B. Colbert, MD, FASN Texas A&M Health Science Center, Dallas, TX

Pablo Garcia, MD Stanford University, Palo Alto, CA

Francesco Iannuzzella, MD, Arcispedale Santa Maria Nuova, Reggio Emilia, Italy Jessica B. Lapasia, Kaiser Permanente Northern California, San Francisco, CA Edgar V. Lerma, MD, FASN University of Illinois at Chicago/Advocate Christ Medical Center, Oak Lawn, IL Ali Poyan Mehr, MD, Kaiser Permanente Northern California, San Francisco, CA Devika Nair, MD, MSCI Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN Vandana Dua Niyyar, MD, Emory University, Atlanta, GA Sayna Norouzi, MD, Baylor College of Medicine, Baylor, TX

Carmen A. Peralta, MD, MAS Cricket Health and University of California, San Francisco, CA

Roger Rodby, MD, Rush University, Chicago, IL Ankur Shah, MD, Brown University, Providence, RI Nikhil Shah, MBBS, DNB University of Alberta, Edmonton, Canada Ilan Zawadzki, Kaiser Permanente Washington, Seattle, WA Sydney Tang, University of Hong Kong, HK

Last Update: Dec 31 2020; 13:15 Eastern

What was updated: updated outcome data including USRDS; added anchor links for iron/epo use; remdesivir

Official Resources

International Society of Nephrology Resource page

American Society of Nephrology COVID-19 resource page and toolkit

Guidance from NICE (UK; PDF link)

CDC guidelines on Infection Prevention and Control Recommendations for Patients with Suspected or Confirmed COVID-19 in Outpatient Hemodialysis Facilities

GlomCon COVID-19 in the CKD/ESRD Patient Population (YouTube)

ERA-EDTA sharing Milan experience on coronavirus management in dialysis centres, published in CKJ

EUDIAL Recommendations for the prevention, mitigation and containment of the emerging SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) pandemic in haemodialysis centres

Review article in Kidney International Naicker (et al, KI 2020); includes guidance from the Chinese and Taiwanese Societies of Nephrology

CKD and ESKD COVID-19 GlomCon Session

Dialysis FAQs

What is the risk of COVID-19 in patients receiving chronic dialysis?

One would think that given the increased risk of the disease in older people, as well as those with hypertension and other comorbid conditions, that the risk would be higher in people on chronic dialysis. This has been borne out to be true. The published literature is collated in a table below, with reports of incidence varying from 2 to 20% for in-centre dialysis patients. An important aspect for patients on hemodialysis (HD) is that they cannot avoid traveling, so safe and secure transportation needs to be addressed. Depending on the spread in HD units, they may also need dialysis in designated shift or centers (more on that below).

This is a good time to be on home dialysis - whether it be peritoneal or home HD.

On March 11, the ASN did a webinar, which has subsequently been turned into a CJASN perspective article, Kliger and Silberzweig (CJASN 2018). Topf summarized the webinar in a Tweetorial. This can be found here. For a beginner, it has very useful details on the virus and the disease, transmission, and precautions to be taken on dialysis. We discuss those details in the questions below as well.

How do we (physicians, nurses, techs, clerks etc.) get up to speed on COVID-19?

All staff should receive training in clinical knowledge about COVID-19, prevention guidelines, and local institutional/hospital protocols.

This training should preferably include (this training can be done online):

How to use different types of masks, how to cover the nose and mouth when coughing, how to dispose of contaminated items in waste receptacles, and how to perform hand hygiene.

Latest care recommendations and epidemic information should be updated and delivered to all medical staff.

To consider and only if needed, train staff to take nasopharyngeal swabs for COVID-19. This is an aerosol generating procedure, so the person performing the test should wear appropriate personal protection equipment (eye protection, respiratory protection, as well as cap and gloves), and one needs the right room as well to contain and clean. This may not be possible in every free standing dialysis facility.

What are the responsibilities of the staff working at a dialysis center?

One of the major concerns in maintaining a safe dialysis environment is preventing the dialysis center itself from being a source of infection. All staff need to make sure they are not infected to prevent them from harming their patients.

All staff need to self-monitor for symptoms of COVID-19 (eg: fever, or new onset cough, fatigue, nausea, diarrhea, anosmia) and notify the medical director or team leader if they develop any symptoms suggestive of COVID-19.

The staff should notify the medical director or team leader if their family members develop symptoms suggestive of COVID-19 infection.

Sick members of the team should stay at home, and should not be in contact with patients or other team members. Duration of self isolation may vary from centre to centre, and whether or not COVID-19 was tested and negative.

What can we tell dialysis patients about life outside the unit?

Though we do not have data to point to, it is intuitive that dialysis patients are part of a susceptible group and need to take extra precautions.

Stay at home while they are not receiving dialysis.

Try as much as possible to use individual transport to the dialysis center and avoid public transportation if possible (see more below on transportation).

Avoid contact with other people including their children and grandchildren. Be aware that young people serve as a vector of the disease, often without symptoms or only minimal symptoms. Dong (Pediatrics 2020).

Family members living with patients on dialysis must understand the precautions to prevent within-family transmission. These include body temperature measurement (at least once a day), personal hygiene, handwashing and prompt reporting of symptoms suggestive of COVID-19.

© The Author(s) 2020. Published by Oxford University Press on behalf of ERA-EDTA. All rights reserved. This article is published and distributed under the terms of the Oxford University Press, Standard Journals Publication Model (link)

What general hygienic measures should we consider adopting in our centers?

Our colleagues from Italy shared a series of recommendations including general hygienic measures. Cozzolino (CKJ 2020)

Put alcohol dispensers in patient rooms, waiting rooms, etc, and advise patients to use them.

Recommend the patients to wash their hands and fistula before starting dialysis.

Nursing and medical staff should wear surgical masks and protective glasses while they are in the dialysis room, wash their hands with soap and water and use alcohol solutions systematically.

If you share dialysis nursing staff between adult and pediatric units, consider permanent separation of staff to minimize risk of cross infection.

© The Author(s) 2020. Published by Oxford University Press on behalf of ERA-EDTA.This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License, which permits non-commercial re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. For commercial re-use, please contact journals.permissions@oup.com (Link)

Nice infographic on preventing transmission by Divya Bajpai. Feel free to copy, print, and use it to educate your patients and staff: PowerPoint | PDF

What is the role of the Medical Director during the COVID-19 pandemic?

Referring physicians, dialysis center staff and patients are all understandably anxious about the implications of COVID-19 for the kidney community. The dialysis center Medical Director plays a critical leadership role in ensuring that safe and effective dialysis care continues through this global health crisis. Being frequently present in the dialysis center, attending staff meetings, and huddles - preferably by teleconference and/or maintaining social distancing - and reviewing specific COVID-19 related plans with operational colleagues can go a long way to reassuring teams.

Although institutions and dialysis organizations are working hard to implement generalized approaches to staff and patient issues related to COVID-19, the Medical Director's knowledge of local resources and care services are invaluable in this scenario. Medical Directors should thoughtfully review rapidly evolving approaches to care and provide feedback and adapt approaches to local care realities.

What do you do if you have patients who have been in contact with people who tested positive for COVID-19?

Following some recommendations coming from our colleagues in Italy. Cozzolino (Clin Kid J 2020).

If the patient doesn’t have any symptoms suggestive of COVID-19: patients must wear a surgical mask when they arrive and during the entire dialysis session. Rigorous application of disinfectants is recommended. If the patient sneezes, use disposable handkerchiefs and throw them away after each single use.

Ideally they should be screened for COVID-19 (see next question for how to arrange for this).

If you have a separate unit for patients with suspected/confirmed COVID-19, they should be transferred there.

If they have to be dialysed in the same unit (with other non-COVID19 patients), use an isolation room if available.

If there is no isolation room, consider using the last shift of the day, the last station in a row to minimize exposure to other patients.

How do you care for a dialysis patient who has symptoms suggestive of COVID-19?

The simple answer is that it depends. It depends on where you practice as well as who oversees that dialysis unit. Over the preceding weeks we have seen a series of recommendations from healthcare systems, professional and scientific societies as well as dialysis providers. These guidelines continue to change on a weekly or daily schedule.

One of the most important steps is screening every patient, every time they present for dialysis. From there you should follow the guidelines of your institution. This may include masking the patient and dialyzing them at a distance from other patients or sending them to the local outpatient testing center or hospital for further evaluation and work up.

While the COVID-19 virus is completely new on a global scale, nephrologists have been here before. Dialysis patients have been at risk during world epidemics recently including SARS, MERS, and the Ebola virus. The advice for protecting patients and health care workers from previous outbreaks still applies today. From an excellent perspective regarding the care of dialysis patients in the Ebola crisis: Boyce and Hymes (CJASN 2018)

Lessons learned from the events in Dallas included the fact that nonspecific signs and symptoms occurring early in the course of infection can delay recognition of Ebola virus disease (EVD) and that inadequate triage practices, suboptimal communication between medical staff, and lack of adequate and appropriate use of personal protective equipment (PPE) can result in nosocomial transmission….Triage strategies should include notifying patients about the signs and symptoms of infection with pathogens causing the outbreak, such as EVD, MERS, SARS, or avian influenza; placing signs with questions about potential exposures and symptoms at entrances; and screening all patients immediately at the time of arrival at the dialysis unit.

This wisdom from previous outbreaks should be applied directly today as infectivity is even more widespread.

Should dialysis staff be doing nasopharyngeal swabs in patients with symptoms, or send them elsewhere?

Following some recommendations from our colleagues in Italy, it might be appropriate to train our staff to take nasopharyngeal swabs for COVID19. Cozzolino (Clin Kid J 2020) There might be a need for us as dialysis providers to help with the diagnosis. It does make sense not to send patients to the emergency departments, which are busy at the best of times. As we mentioned above, however, this is an aerosol generating procedure, and requires PPE and additional safeguards which may or may not be available in all dialysis facilities.

In some centres, a designated COVID-19 unit has been created, which allows for screening of potential COVID-19 patients, and isolating them as well (‘cohorting’ them together, so to speak) until tests come back negative, or they are no longer infectious.

Otherwise, consult local authorities and public health to plan for referral of dialysis patients for testing.

How should patients with COVID-19 and mild symptoms (not needing hospitalization) arrange transportation? (since they cannot self-isolate)?

Dialysis is considered ‘essential medical treatment’, so patients can and should come to treatment even if a lockdown is in place. Each dialysis facility should provide a letter if necessary to the transportation company explaining that dialysis is an essential medical treatment and that the patient will require continued service even in event of a lockdown. On the other hand, we do not want the driver - or other people using the same transportation services - to get infected. Patient privacy needs to be weighed against public health needs, see this discussion on twitter. The following are suggestions to consider:

Drivers should be informed that the patient has COVID-19

Infected patients should not carpool with other patients

Suspected patients should wear masks during the travel

Isolate any drivers who have possibly been exposed

Thoroughly sanitize vehicles that have been exposed

Use sanitizers between rides and nightly deep cleans

Encourage drivers to wear masks and gloves provided by transportation company

Hand sanitizers need to be available in vehicles for patients and drivers

Drivers should report riders with symptoms to the facility

Transportation with private vehicles should be arranged if possible for symptomatic patients.

Can you use Hep B isolation rooms for COVID-19 positive patients?

Hepatitis B isolation rooms may be used to dialyze patients if:

The patient with suspected or confirmed COVID-19 is hepatitis B surface antigen positive or

The patient is hepatitis B surface antigen positive and the facility has a detailed plan to clean the room and allow for 270 minutes before any hepatitis B positive patients arrive for treatment. (note: the 270 minute guidance is from the ASN webinar. We are not sure of the evidence base behind this very specific advice).

The facility has no hepatitis B surface antigen positive patients who would require treatment in the isolation room.

How should waiting areas, counters, etc. be cleaned in a unit and how often?

Routine cleaning and disinfection are appropriate for COVID-19 in dialysis settings.

Any surface, supplies, or equipment (e.g., dialysis machine) located within 6 feet of symptomatic patients should be disinfected or discarded.

Products with EPA-approved emerging viral pathogens claims are recommended for use against COVID-19. Refer to List N on the EPA website for EPA-registered disinfectants that are qualified for use against SARS-CoV-2.

Personnel who perform the terminal clean should wear a gown and gloves. A face mask and eye protection should be added if splashes or sprays during cleaning and disinfection activities are anticipated or otherwise required based on the selected cleaning products.

Waiting areas including surfaces such as chairs, door knobs and rails should be cleaned multiple times a day, ideally after each shift with bleach based disinfectants. (Protocols may vary with each dialysis unit)

Should staff age drive assignments?

This is a good question to ask. We don’t have a satisfactory answer, given that, with isolation of exposed staff, and increased workload, the need to have all hands available to work is crucial.

When can COVID-19 positive patients cohorted in a dedicated HD unit go back to their regular unit?

In other words, when can transmission-based precautions be discontinued? The wag might say, once they are COVID-19 negative, duh! But that’s easier said than done. Every individual’s course is slightly different. Some patients, it seems, remain COVID-19 positive for a long duration. Should they remain in the separate unit until they are negative? Though that may seem the safer option, it also means hardship for the individual who has to travel to a possibly inconvenient time & place. Secondly, it also might mean less spots available in the dedicated COVID-19 unit for patients who might need them. Again, this is an area where robust evidence has lagged behind, and the discussion below is based on biology and pragmatism than clinical trials.

The strategies widely adopted are based on PCR testing, time, or symptoms (see CDC guidance, July 17, 2020 for more details and links).

Testing based strategy: In this strategy, the patient remains under isolation and/or the COVID-19 cohorted dialysis shift/unit until they test negative for COVID-19 by PCR, either once or sometimes twice. While this seems like a safe strategy to adopt, there are downsides, such as inconvenience for the patient, and the possibility of tying up isolation spots/stations. Does the PCR test mean that a patient is truly infectious? Prolonged viral shedding does not mean someone is infectious: the presence of the RNA might reflect dead viral particles. If the isolated virus grows in a culture, that would prove these are what we would think as live virions, termed as ‘replication competent virus’. (We use the term live and dead very loosely, as viruses are tricky to pigeonhole. As an example, see this debate, or this philosophical article on viruses and the meaning of life). In the evidence covered here (CDC Decision Memo, July 22, 2020), the literature in this area is discussed including that though PCR has tested positive for up to 12 weeks, replication competent virus was not detected in these samples and contacts with these patients did not result in new infections. Nevertheless it is possible that in immunocompromised patients prolonged virus shedding may be seen. In this study (van Kampen et al, MedRXiv 2020) of 129 hospitalized patients with COVID-19, the median duration of shedding was 8 days post onset of symptoms (IQR 5-11) and the probability of detecting infectious virus dropped below 5% at the time point of 15 days onset of symptoms, see figure below.

Figure 1 from van Kampen et al, MedRXiv 2020

Being immunocompromised (solid organ or bone marrow transplant in this study) was associated with longer virus shedding in univariate analysis in this study.

This leads naturally to a symptom-based strategy

Symptom based strategy: Based on the data above, this strategy means that one waits for a fixed period of time after symptoms appear AND disappear.

Thus, for patients with mild to moderate illness who are not severely immunocompromised:

At least 10 days have passed since symptoms first appeared and

At least 24 hours have passed since last fever without the use of fever-reducing medications and

Symptoms (e.g., cough, shortness of breath) have improved

For patients with severe to critical illness or who are severely immunocompromised:

At least 20 days have passed since symptoms first appeared and

At least 24 hours have passed since last fever without the use of fever-reducing medications and

Symptoms (e.g., cough, shortness of breath) have improved

Asymptomatic patients: The same CDC guidance (updated July 17 2020) suggests that isolation precautions should be undertaken for 10 days after the positive test in those who are not immunocompromised, or 20 days after a positive test for those who are severely immunocompromised. Of course this assumes they don’t develop symptoms after the initial test.

In summary, while the data is fairly robust that the risk of remaining infections drops as outlined above in the general population, evidence of the same is not yet available for people with ESKD. They are, by definition, immunocompromised, and may have prolonged viral shedding, posing a potential risk if assimilated back to the usual dialysis units earlier, based purely on a symptom/time based strategy. As such, many dialysis organizations continue to use a test based strategy though some allow managing nephrologists to use a symptom based strategy if they deem appropriate.

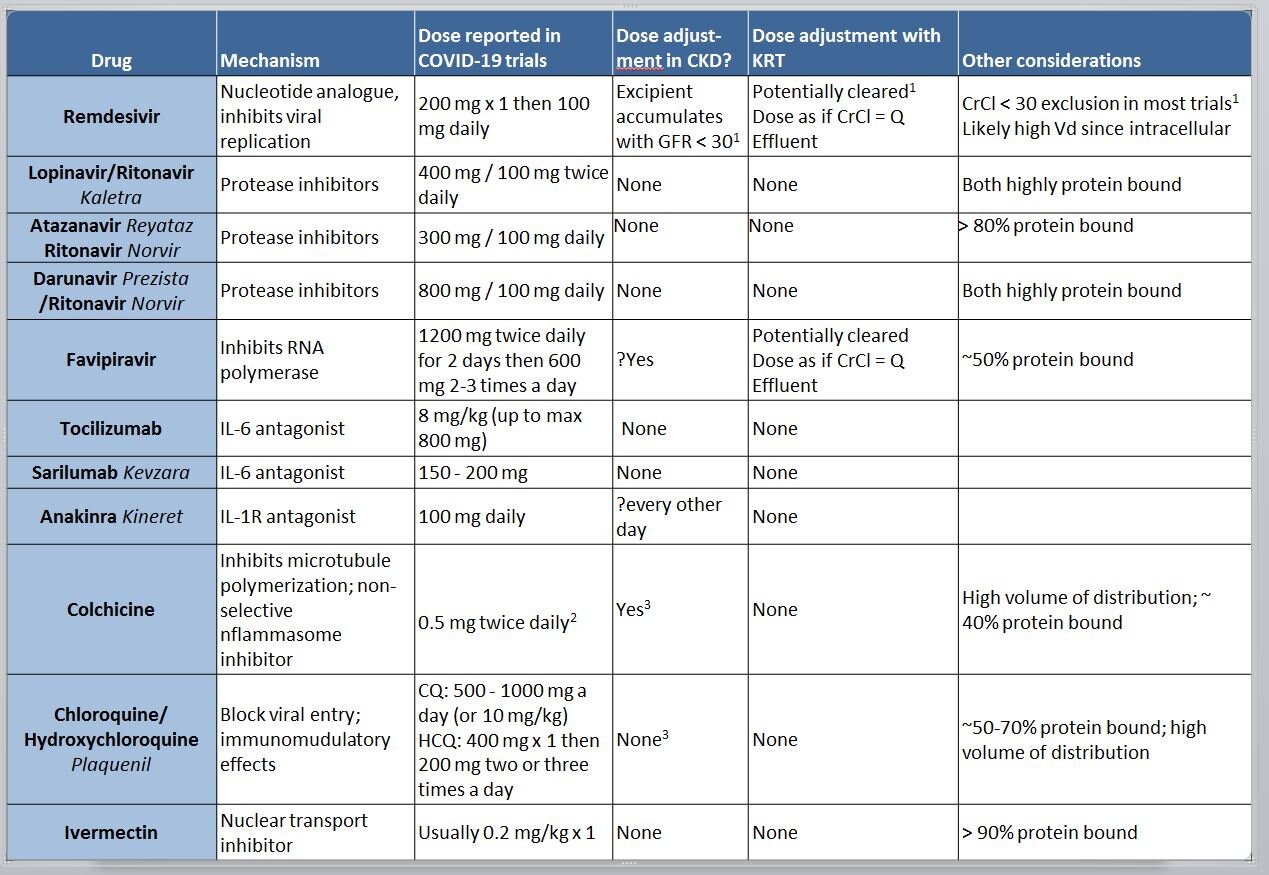

How do you dose the experimental drugs being used in COVID-19 in dialysis patients? Dosing change and clearance?

There are no proven and established medicines which have been clearly shown to be beneficial in COVID-19. However, it is possible that they will be used in patients with CKD, so it is useful to review the clearance of these drugs. Some of them (e.g. chloroquine) have been around for many years, whereas others (eg remdesivir) have not been officially licensed/approved for open use yet, with access mostly from compassionate use or as part of clinical trials. For drugs such as chloroquine, many different dosage regimens have been floated around (mostly because of the woeful lack of evidence and leaps of faith involved), so a careful review of pharmacokinetics and discussion with a pharmacist is useful.

Apart from the molecular size (ie small molecules will be removed by dialysis), and protein binding (protein bound drugs are not removed by dialysis), the other major criterion is the volume of distribution. With a large volume of distribution (eg drug present in tissues, and not just in blood), even if dialysis removes it from the circulation, it won’t be effectively cleared, because of high levels in the tissues. Again, for chloroquine, this is quite high - which means most of it is distributed in the tissues, and dialysis will not remove a significant amount.

Names in italics refer to brand names.

This is a common reported exclusion. See discussion of this in this Twitter thread, and more below

Dose in gout is usually 0.6 mg, this dose is reported for the COLCORONA trial

These drugs do have some clearance by kidneys, so accumulation with occur with chronic dosing, not relevant in the COVID-19 setting

Specifically, what should we know about Remdesivir and its dosing in CKD or Dialysis?

Remdesivir is a prodrug (or a proTIDE, aka pro-nucleotide to be precise) that gets converted to GS-441524 in vivo, which is the active anti-viral agent. Its phosphorylated form functions as an adenosine nucleotide triphosphate analog, which interferes with the action of viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerase, decreasing viral replication (Eastman et al, ACS Cent Sci 2020).

The prodrug half life is about 20 minutes after intravenous infusion, but the active metabolite has sustained intracellular levels, and a half life of about 20 hours (Sheahan et al, Sci Trans Med 2017). Most of the elimination is through the kidney (~75%) and 18% in feces. Not much is known about its volume of distribution or protein binding in the literature, but given its half-life and rapid intracellular entry, volume of distribution would be expected to be high.

The dosing in AKI is complicated less because of the drug, and more related to the excipient, a cyclodextrine (sulfobutylether-β-cyclodextrin sodium salt or SBECD). SBECD is cleared by the kidneys and accumulates when the GFR is < 30 in particular. There is additional concern that SBECD can cause AKI via osmotic tubulopathy, with anecdotal reports from its use as an excipient for voriconazole (F. Marty, Twitter, 2020). Hence once the GFR < 30, even the FDA fact sheet (link, PDF) suggests using risk/benefit analysis to guide its usage, with some advice from experts (F. Marty, Twitter, 2020) that the risk/benefit suggests we should use it on patients on KRT. Since based on the information we have with a molecular weight of 600 Da, it is likely to be cleared to some extent, so would be reasonable to give the dose after HD in patients on hemodialysis. Also see this comprehensive review of the topic (Adamsick et al, JASN 2020) which suggests similar advice.

We review additional data on remdesivir efficacy as well as its use in CKD from 4 case series in a December NephJC chat here. See a visual abstract as well here:

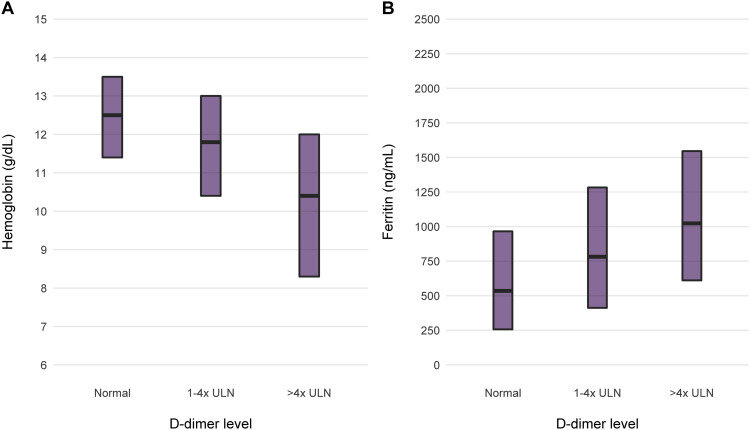

Should we use iron and erythropoietin in patients infected with COVID-19?

In chronic HD, anemia is common, and iron and erythropoietin usage to correct the anemia is also pretty common. Post PIVOTAL (see NephJC discussion) we have pivoted to using more iron and post CHOIR/TREAT (see NephMadness discussion, and commentary by Coyne) we have settled to being satisfied at lower hemoglobin levels. When there is an active infection, however, intravenous iron use is generally avoided, since microbes thrive on iron (think of bacteria growing on blood agar from your remote microbiology class). The role of iron for viral replication is less established, though iron is needed for several cellular activities and has a putative role for certain viral infections such as HIV and Hepatitis C (see Drakesmith et al, Nat Rev Microbiol, 2008). Presumably something similar might apply with COVID-19. Additionally, the severe inflammation seen in COVID-19 is accompanied by a rise in serum ferritin as well (eg Zhou et al, Lancet 2020 and Fishbane et al, AJKD 2020). We do know of course, that ferritin is not a marker of iron storage or iron repletion - in this scenario in particular it is an acute phase reactant.

Figure 1 from Fishbane et al, AJKD 2020

So in the setting of active COVID infection, backing off on iron seems reasonable, as one does with any other active infections. Similarly, patients with severe inflammation are hyporesponsive to erythropoietin (Chawla et al, HD International 2009). Additionally, patients with COVID-19 may have a prothrombotic state, and higher erythropoietin dosages and higher hemoglobins have been associated with more thrombosis. Hence, withholding erythropoietin and having a low transfusion threshold (eg only at hemoglobin levels < 7 or 8g/dL as suggested in this conversation) in the sicker patient, and leaving them on maintenance doses but with a lower hemoglobin target for the stable patient are some of the suggested strategies (Fishbane et al, AJKD 2020).

What is the clinical course of dialysis patients with CoVID-19?

We initially knew that age seems to be strongly associated with the severity of COVID-19. Age also associates very strongly with CKD. However, not every country or region has the same policies for starting dialysis, especially at older ages. As an example, in this DOPPS study by Canaud (CJASN 2011), the proportion of patients who were > 75 years in Belgium and France was markedly high compared to Japan and UK.

How about China? The mean age there for HD patients was 51 years in this study by Sun et al (Med Sci Monit 2018). Hence extrapolating from China to Europe to North America to elsewhere in the world should be done thoughtfully. As with AKI, the initial data about the milder course have been upended by subsequent literature as seen below.

Initial Data: Misleading

A preprint from a single chinese HD unit (Ma et al, MedRXiv 2020) suggested that the course of COVID-19 was milder - and the speculation is that this is due to the lack of a robust immune response (which leads to the inflammatory response in ARDS). In this case series which includes 230 patients on HD at one unit, 37 patients developed COVID-19, but all cases were mild and did not need admission to the ICU. Indeed, 27 of the 37 (72%) patients with COVID-19 were asymptomatic and only picked up through screening. Patients did demonstrate the usual lymphopenia, but the levels of measured cytokines were lower than with patients not on HD with COVID-19. Six of these patients with COVID-19 died during the follow up period. Tragically the causes of death in these patients were potentially related to missed and shortened dialysis treatments (eg hyperkalemia, volume overload, stroke) and not respiratory complications of COVID-19. This is confirmed by a correspondence published since in Kidney Medicine (Wang, Kidney Medicine, 2020). This underscores the need to reassure patients that everything is being done to protect their health and that dialysis remains a critical part of their overall care.

A case report published in Kidney Medicine also reported a good outcome, although this patient did develop pneumonia, and was treated with antivirals. None of the other patients in the unit (exposed to this patient) developed COVID-19, though they were isolated for the next 14 days.

Subsequent Literature

On the other hand, from the ASN webinar discussed above, 2 of the initial patients in Seattle who sadly had a mortal outcome were HD patients. These were probably the same patients included in the case series (Arentz et al, JAMA, 2020) of 21 critically ill patients who developed COVID-19.

We now have data from Italy, Spain, UK, and US as well as a larger study from Wuhan. The overall incidence of COVID-19 in dialysis patients seems to vary (probably based on underlying population incidence, testing rates and startegies, precautions taken and many more). However, the mortality rates amongst in-centre hemodialysis patients who develop COVID-19 seems to be in the range of 25 - 30%.

Sources: UK Renal Registry First Wave data; ERA-EDTA registry; Xiong et al JASN 2020; Fisher et al, Kidney360, 2020; Corbett et al, JASN 2020; Medicare Claims till Sep 2020; DCI Nov 2020. Archived version of table available here.

A preliminary Medicare COVID-19 snapshot of claims and encounter data from services rendered through September 12, 2020 found the highest burden of COVID-19 in patients with ESKD. 7,165 cases were found per 100,000 beneficiaries, about 5 times higher than the overall Medicare rate of 1,843 cases per 100,000 beneficiaries. Similarly hospitalization rates were 7 times higher at 3,583 for ESKD compared to 51 per 100,000 for the general medicare population. Dialysis Clinic Inc (DCI), a non-profit dialysis organization caring for approximately maintenance dialysis 15,000, has been publishing weekly updates of the COVID-19 response. As of November 22 2020, 1,477 (3.7% assuming 15,000) patients in outpatient clinics had tested positive for COVID. Just over 40 % of cases were from group homes. Mortality overall was 16.9%, roughly half from group homes, hence along the same lines as we see in the table above.

The 2020 annual USRDS report has a special supplement on COVID with a lot of granular data, on incidence, racial and sex breakdown, hospitalizations etc. This is up to the first half of 2020, and the entire report should be read to make sense of what happened in the ESKD population. A small sobering statistic: between weeks 14 and 17, all-cause mortality was 37% higher in patients receiving dialysis than during the same period of 2017-2019, as seen in the figure below.

For ease, Eric Weinhandl has summarised the highlights in this twitter thread

Should we rethink Resuscitation during the COVID-19 pandemic?

Among ESKD patients who have undergone cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) while in-hospital, only ~ 15% are discharged home (Saeed et al, JASN 2015). Also keep in mind that these are scenarios where the treating team thought CPR was reasonable.

In COVID-19 (not with ESKD), investigators from Wuhan (Shao et al, Resuscitation, 2020) reported 136 cardiac arrests. The most common rhythm seen was asystole (90%). Restoration of spontaneous circulation was achieved in 13% patients, and only 3% patients survived to 30 days with only 1/136 having a favorable neurological outcome.

Lastly, CPR in #COVID-19 is an aerosol generating procedure. Hence, while performing CPR, providers should be wearing appropriate PPE. Additionally, CPR should be performed in Airborne Infection Isolation Rooms (AIIRs) (see CPR guidance from the American Heart Association, PDF link). So dialysis centres need to consider their preparedness for performing CPR.

Many of these issues are considered in detail in this editorial (Fritz et al, BMJ, 2020). As the editorialists state, ‘the pandemic has changed the risk-benefit balance for CPR: from “there is no harm in trying” to “there is little benefit to the patient, and potentially significant harm to staff.” ‘ Whatever paths we take, it is important to maintain trust, establish a shared understanding of the patient’s condition, an understanding of what is valued by the patient, and what treatments will realistically help them.

Overall, these issues highlight the importance of having advance directives in place and having regular end-of-life care discussions with patients, as appropriate (see recent coverage from 2020 #NephMadness for more).

Should we change the approach to vascular access issues?

Vascular access in dialysis does need ongoing maintenance:

excessive bleeding

AVF/AVG might clot

poor function

In view of the COVID19 crisis, most institutions and authorities are slowing down or stopping elective surgeries. Are vascular access procedures truly elective?

Dialysis access is a patient’s lifeline and delay in procedures required to maintain dialysis access patency may be life-threatening. The American Society of Diagnostic and Interventional Nephrology (ASDIN) and the Vascular Access Society of the Americas (VASA) have issued a joint statement recommending that these dialysis access procedures be categorized as a higher tier, to allow certain select procedures to continue. This will not only allow dialysis patients in the outpatient settings to continue to receive their care uninterrupted but will also mitigate the burden on hospitals for admissions and urgent interventions (see the ASDIN statement from Hentschel et al).

Should we create new Vascular Access during these times?

Every centre will have a different take on this. As we discuss in the section on PD catheter insertions, this is something that is not entirely extraordinary and can still be considered in select patients. Patients needing to start dialysis will need to have some procedure, if the vasculature looks favorable, why not consider an AVF compared to a tunneled catheter? Another option to consider is also the endoAVF, especially if one already has the setup and expertise. See the Nephmadness post for more on this topic.

Home Dialysis FAQs

What measures can nephrologists take to protect patients on home dialysis modalities?

One important way we can help our patients on home dialysis is to minimize their visits to health care facilities. We can bundle needed activities (e.g. ESA administration, in person assessment, lab draws) into a single visit at a lower frequency whenever feasible and allowed. If not already happening, centers should revisit home administration of ESAs with each patient. Home dialysis suppliers are in some instances delivering alcohol based hand sanitizer and some personal protective equipment along with home dialysis supplies reducing the impact on home dialysis center inventories of these items. Given concerns about supply chain many home centers are encouraging patients to have a minimum of 2 weeks of backup dialysis supplies available.

What is the role of telehealth for patients on dialysis?

Telemedicine allows the doctor to continue to monitor patients without putting them, or the medical staff at risk by having additional social contact. This is an excellent option for home dialysis patients, but also may be an option for satellite dialysis units requiring travel for physical in-person visits. Reimbursement guidelines are changing - so follow the rules closely for more information.

Is this an opportunity to increase home dialysis?

As is apparent, being on home dialysis also makes social distancing easier. Patients on PD do not need to come in-centre 3 times a week, requiring exposure to transportation, other patients in-centre as well as staff. Can we continue to grow home dialysis during COVID-19? The major hurdles are:

Arranging for PD catheter insertions (since elective surgeries are being cancelled at many centres)

Arranging for home dialysis training (which takes a few days coming to a training centre, and requires dialysis staff who might be needed elsewhere)

Which patients might qualify for a new PD start?

Incident ESKD patients

Patients with AKI who survive ICU/CKRT but remain dialysis dependent awaiting recovery of AKI

Failing transplants

How do we arrange for PD catheter insertions?

Surgeons: With most surgeons cancelling elective surgeries, they may have the bandwidth to put in PD catheters within 48-72 hours. Though PD catheter insertion is not considered urgent or lifesaving surgery, detailed arguments may need to be made to site admins to allow continued PD access procedures during the pandemic. Each PD catheter inserted is another patient who will avoid a CVC insertion (radiology time), incenter dialysis (capacity consumption for incenter dialysis, multiple risks of exposure with 3/week HD schedule) and continued function of the PD unit.

Interventional Radiology or Nephrology: If the centre already has an established program via IR or nephrology, these should be continued, for the same reasons detailed above.

Desperate measures - Stab / Stiff catheter insertions at bedside - If situation really becomes extreme, dialysis can also be provided using bedside insertion of stiff catheters as temporising measures. Patient is mandated to be supine for the entire duration of the stiff catheter insertion, and this can have its own problems

Urgent PD start Prescription

Urgent PD catheter prescriptions - PD can be started within 24-48 hours of an urgent PD catheter insertion using low volumes and supine position. It is suggested using cyclers if available to reduce the nursing workload. These options are also possible in an outpatient setting. PD training spaces can be repurposed to have new PD patients come to outpatient units for 6-8 hours and get 3-4 exchanges on the cycler. To avoid leaks, the abdomen should be left dry during the rest of the time. Here is an excellent review: Arramreddy et al (AJKD, 2014) and a representative study: Povlsen et al (PDI, 2015).

Contingency FAQs

What are potential plans that can be implemented when hemodialysis capacity is overwhelmed?

We have discussed the kidney replacement therapy plans for patients in the ICU in another post. Here we will explore the possible scenarios and solutions for the patients not in ICU.

Outpatient dialysis will continue to challenge the infrastructure to accommodate:

Dialysis staff and physicians either needing to self-isolate due to symptoms or exposure, or from developing COVID-19.

Prevalent in-center patients

Movement of patients

Incident ESKD patients

Patients with AKI who survive ICU/CKRT but remain dialysis dependent awaiting recovery of AKI.

Failing transplants

Home dialysis patients - needing respite therapy for patient/care-giver infection and need to self-isolate.

New non-critically ill patients requiring dialysis for AKI.

Not only will these increased numbers stretch the available capacity of dialysis beds/chairs and machines, but they constitute a unique population which will repeatedly be at risk of exposure to COVID-19. Eventually there may come a time when there will not be enough dialysis spots for providing hemodialysis to this population.

How can we increase the capacity to do hemodialysis?

Increasing in-center hemodialysis capacity

Center hours - 24x7 available center hours - by making the center available overnight potentially add 1 - 2 extra shifts - this may be one of the easiest and doable first steps. Infrastructure is ready and outpatients can continue the daytime dialysis and the overnight spots can potentially be used for the inpatient dialysis population who are in the hospital. Innovative staffing strategies may be required. Work load will certainly increase, with increasing machine turn-around (preparing and disinfecting).

Dialysis Prescription changes

If the above strategy falls short, then changes to the dialysis prescription can be a consideration. The following are the possibilities

Treatment time reduced; Frequency same

Treatment time same/increased; Frequency reduced: e.g. twice a week dialysis for most patients. This could work especially for those with residual kidney function, or those who do not come in with hyperkalemia or pulmonary edema with three times a week dialysis. This might be the most practical solution - but it adds significantly to the logistical complexity of scheduling patients

Treatment time reduced; Frequency also reduced: This can be a challenge, however in those patients with excellent urine output and good dietary compliance, such an option is possible.

All of these options will require close monitoring of these patients, however care should be taken not to burden our labs with excess testing.

Home hemodialysis spaces and machines

While home dialysis training should continue (useful to keep a patient away from the hospital/incenter setting) the home dialysis spots and machines can be used for running “in-center” dialysis after the training hours.

What are the preparations for dialysis patients who cannot be dialyzed? (transportation issues, no equipment, no staff and lockdowns)

Hopefully this time never comes during the pandemic, but like with everything, being prepared for all eventualities is prudent. There may come time when we may have to turn patients away from dialysis. In desperate situations like these we need to give them good advice for this period and hope for the best.

Some strategies for ESKD patients not getting any dialysis -

Reiterate and reinforce both salt and fluid restriction, and potassium restriction

Availability of high dose diuretics (if appropriate)

Potassium binding agents

Temporary discontinuation of ACEi/ARB/Spironolactone if appropriate, to reduce risk of hyperkalemia

What should home dialysis patients do if masks and hand sanitizers are not available?

Self care dialysis relies very heavily on the aseptic technique meticulously followed by the home dialysis patients. Access related infections - central lines/AVFs infections in HHD and exit site infection/tunnel infection and peritonitis in PD are some of the most common reasons for technique failure for home dialysis patients. In most cases technique failure essentially means that these patients will return to in-centre dialysis. the key to prevent infection related technique failure is meticulous aseptic technique. Around the world, current aseptic technique for home dialysis focuses on careful hand washing, use of alcohol based hand gel/sanitizer and the use of masks to prevent accidental droplet contamination during connections and disconnections and handling of dialysis access. With the current shortage of PPE and hand sanitizer, this places the home dialysis patients at increased risk of infections. While most programs and dialysis companies are scrambling to arrange masks and hand sanitizers for their home dialysis - the following suggestions apply to those home dialysis patients who will run out.

Masks

Masks are primarily used for preventing accidental droplet contamination from the patients oral and respiratory tracts (coughing, sneezing, talking, etc ) during connections. Are any specific types of masks required for this prevention? Surgical masks are desirable, cloth masks have been used and there have been a couple of studies that have even suggested masks may not be mandatory. The ISPD guidelines mention that masks are optional. In the current scenario where surgical masks are next to impossible to find, the options can be -

Reuse of current available surgical masks - Unless visibly soiled, surgical masks may be reused.

Cloth masks - of a fabric that will reduce droplet transmission. The suggestion will be using the masks and then wash them for reuse. (eg Montrasio masks).

No masks - It has been shown in a study that masks did not change the incidence of peritonitis in a two decade old study which has not been repeated. Figueiredo, AE, Poli de Figueiredo, CE, & d’Avila, DO. Peritonitis prevention in CAPD: to mask or not? Peritoneal Dialysis International 2000; 20(3):354-358.

Hand Sanitizers

There have been studies that have demonstrated that excellent hand hygiene works in prevention of infections with alcohol based hand sanitizers having the best outcomes (Figuerido et al, PDI 2013 and Gruer et al, J Hosp Inf, 1984). When the alcohol based hand sanitizer is unavailable the options are:

Alternate hand sanitizers - Several independent breweries have stepped up to provide the alcohol based hand sanitizers produced according to the WHO formula - these may or may not have the requisite FDA/Health Canada official approvals, but they can be considered.

Excellent hand washing to continue

Sodium hypochlorite solutions: consider having cloth strips soaked kept at bedside - to be used if hooked to a machine and not possible to use soap and water for hand washing.

FAQs for Glomerulonephritis and Immunosuppression

This guide is limited by the lack of available evidence is reflect an overall opinion on the subject matter, which requires adoption and modification in individual scenarios. The ultimate decision about the most appropriate next steps in the management of this patient rests within the treating physician

The key 3 principles here will be further described below

Minimize healthcare exposure (incl. clinic visits, urgent care, ER, hospital visits)

Minimize IS to the extent allowable without risking relapse

Firstline therapies may need to be reconsidered and replaced by second- and third-line agents

Of course, the general principle of social distancing, hygiene, washing hands, not touching face etc., and usual prophylactic vaccinations and medications should be emphasized.

A. Minimize healthcare exposure:

Decrease frequency of blood draws

Consolidate labs with other specialties’ needs

Have patient present for blood draws at times of less traffic (very early am, later in the week) and with KP MDO appt you may schedule lab visits for your patients.

Patient may order Albustix from Amazon so they can self-monitor urines for protein, or blood e.g. in MCD, LN, or ANCA when in remission and/or currently on a steroid taper.

Encourage mail order pharmacy use when possible. Delivery times have been reduced, and some areas now have same day delivery using the “urgent home delivery” tab for patients who have urgent need for a medication”

Avoid biopsies, unless unclear RPGN, and consider making treatment decisions based on laboratory and clinical presentation.

Examples may include:

A patient with a history of lupus nephritis has symptoms and laboratory findings of a possible relapse.

Patient with history of MCD is now nephrotic again.

Patient with history of PLA2R membranous has worsening proteinuria (+/-rising PLA2R titer).

Patient with history of ANCA GN has rising titer, proteinuria and creatinine.

B. Minimize IS to the extent allowable:

Do not take patient off their maintenance IS as a relapse may require more aggressive treatment and therefore counterproductive.

Also note that frankly nephrotic patients or those with RPGN/vasculitis are immunosuppressed and the benefit of treatment could outweigh the risk of immunosuppression.

However, this is now the time to review patients’ charts and assess whether they are behind the schedule of standard dose de-escalation

Consider using reduced dose steroids regimens for indications where reduced dose steroid has shown to be equally effective (ANCA, LN). PEXIVAS low dose steroid regimen was following:

Consider holding IS medication for slow progressive disorders with stable kidney function, such as IgA nephropathy with mild moderate proteinuria.

C. Reassessment of first line agents:

Consider using CNI as first line agent for adult MCD, FSGS. Consider steroid and MMF as second line agents (? stronger immunosuppressive effect, and higher risk for viral infection). Avoid cyclophosphamide and rituximab if possible.

Consider using CNI as first line agent for membranous nephropathy. Rationale: CNI are reasonable effective in alleviating nephrotic syndrome and can be down titrated in the setting of acute infection whereas cyclophosphamide and rituximab have long lasting effects.

Consider using MMF as first line agent for Lupus nephritis – and if possible, avoid cyclophosphamide and rituximab. Rationale: MMF could be down titrated in the setting of acute infection whereas cyclophosphamide and rituximab have long lasting effects).

In severe SLE may consider IVIG, which is immunomodulatory and has potentially some efficacy without being immunosuppressive.

Plasmapheresis use should be reserved for indications where strong efficacy evidence is available (e.g. anti-GBM syndrome, hyper viscosity syndrome). In ANCA vasculitis it was not shown to be of additional benefit. Its use should be assessed on an individual basis and assessed in light of significant immunosuppression, exposure to invasive treatment and healthcare environment, resource utilization etc.

Additional information of management of GN and transplant patients in the setting of COVID19 on https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XDZDeCm7Qgw

A review in CJASN (Bomback et al, CJASN 2020) covers the same topics with similar advice:

List of updates

March 24: Page Launched

March 24: list of contributors added, link to Byrd’s words

March 25: list of contributors added, vascular access section

March 27: link to Letter from Wang in KM; Discussion on creation of new vascular access; links to second ASN Webinar and ISN resources

March 28: Drug dosing table edited

March 29: Infographic added

March 30: Added GlomCon Video

April 23: Mask, sanitizer shortage for home dialysis patients

April 28: Resuscitation in dialysis; immunosuppression use during pandemic

July 3: Dialysis outcomes updated

July 27: Dialysis outcomes from Scotland and US data

July 28: Added sections on how long to isolate; and can iron and epo be used with COVID-10

Dec 31 2020: updated outcome data including USRDS; added anchor links for iron/epo use; remdesivir