#NephJC chat

Tuesday Nov 1st 9 pm Eastern

Wednesday 8 pm GMT, 1 pm Pacific

2016 Sep 29. pii: ASN.2016010021. [Epub ahead of print]

Estimating the Risk of Radiocontrast-Associated Nephropathy.

Wilhelm-Leen E, Montez-Rath ME, Chertow G.

Full text courtesy JASN available at this link: Full Text

Background

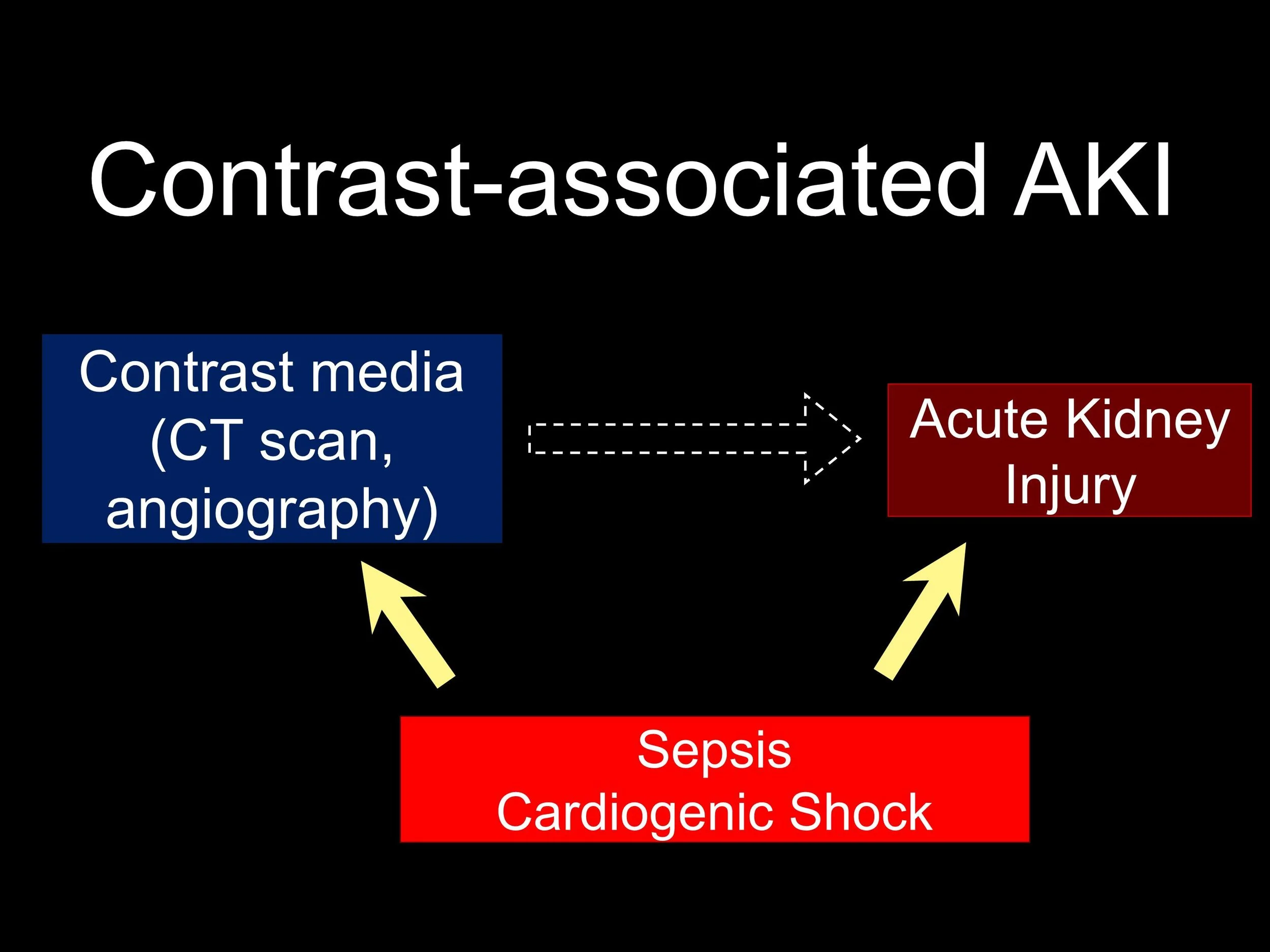

Iodinated contrast is well known to cause acute kidney injury (AKI), mainly from its physico-chemical properties, and is commonly cited as being the third most common cause of AKI in hospitalized patients. But is this really true? Even the term contrast-induced AKI (CI-AKI) is evolving into contrast-associated AKI (CA-AKI), emphasizing the possibility that contrast is merely an 'innocent bystander' previously found guilty by association.

Contrast associated nephropathy (CAN), the term preferred by these authors, is defined as a 25% increase in creatinine from baseline or a rise in the serum creatinine of 0.5 mg/dl (44 micromol) or more within 72 hours of receiving intravenous or intra-arterial contrast.

The incidence of CAN in the published literature varies from <1% to > 30%. However, recent work by McDonald et al showed no increased AKI following administration of intravenous contrast even in high-risk patients with chronic kidney disease or diabetes mellitus. Additionally, another study reported a higher incidence of AKI in patients who did not even receive contrast agent as compared to those who underwent a contrasted study. Needless to say, one cannot really perform a randomized trial of contrast versus no contrast to answer this question (see more from a #DreamRCT proposal here by Chi Chu).

The authors in the present study sought to determine the burden and risk of AKI in hospitalized patients who received contrast as compared to patients with similar comorbidities who did not receive a contrast agent.

Study Hypothesis

Risk of AKI in hospitalized patients who receive contrast does not differ dramatically from the patients who did not receive contrast.

Methods

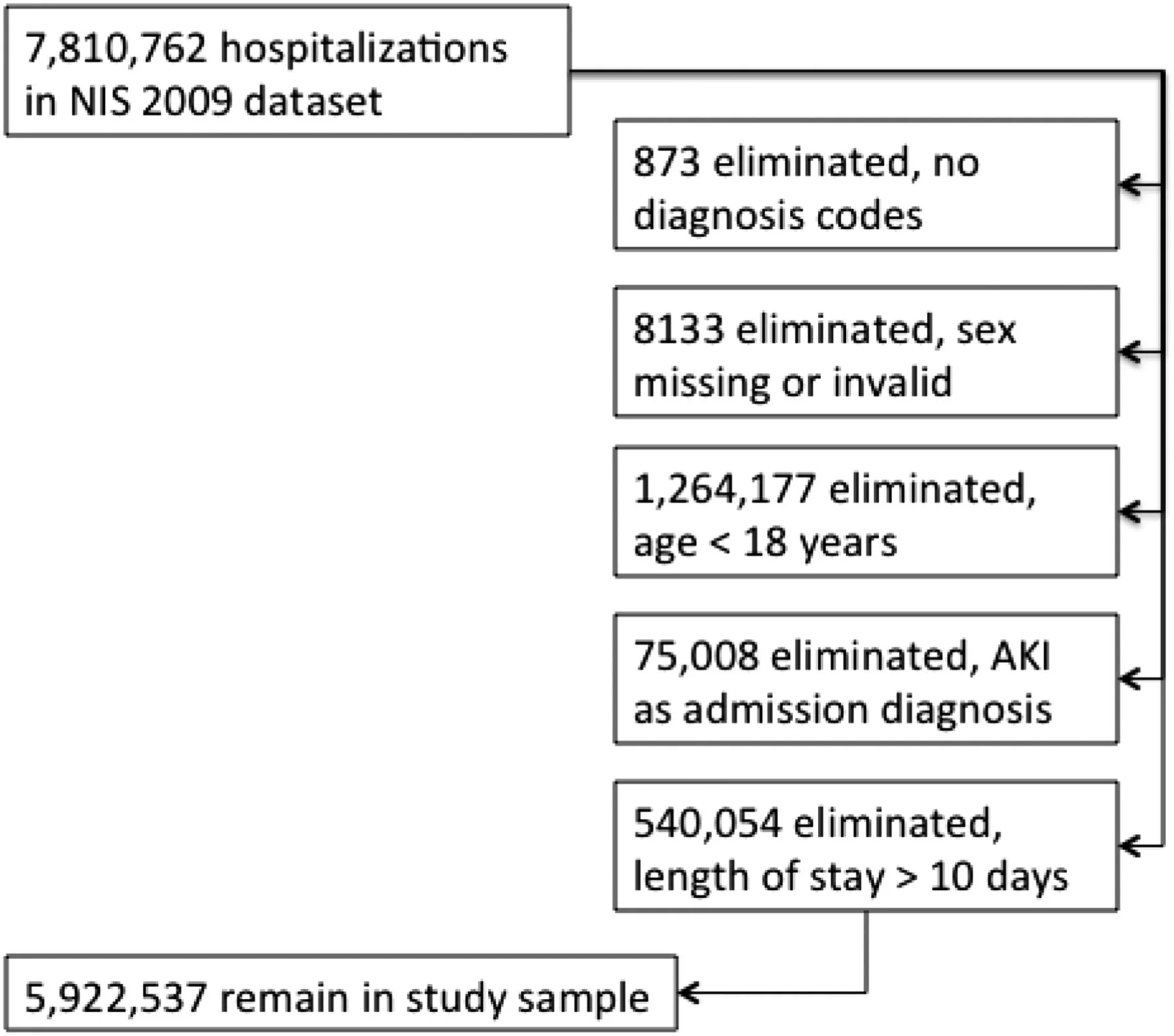

Data Source: Data was collected from the 2009 NIH database, which is the largest publicly available all-payer inpatient database in the United States. It contains administrative data from approximately 8,000,000 hospitalizations per year, representing 96% of the United States population.

Inclusion Criteria: 5,922,537 patients ≥18 years of age were included with an admitting diagnosis other than AKI and ≤10 days of hospitalization.

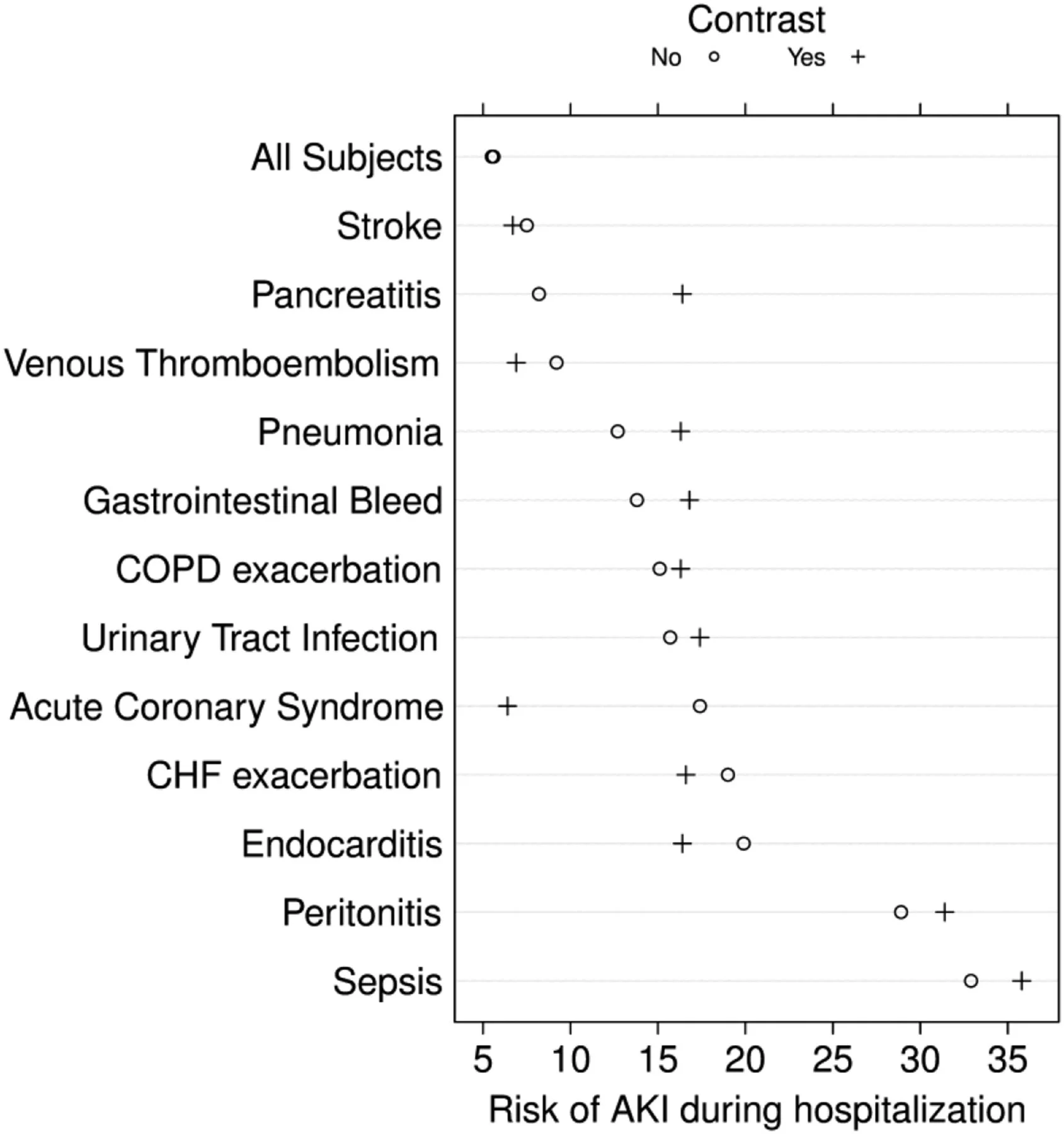

Figure 1: from Wilhelm-Leen et al, JASN 2016

Study Variables: ICD 9 codes were uses to identify the primary outcome of occurrence of AKI, the independent variable of contrast, pre existing comorbidities and Charlson/Elixhauser comorbidity index

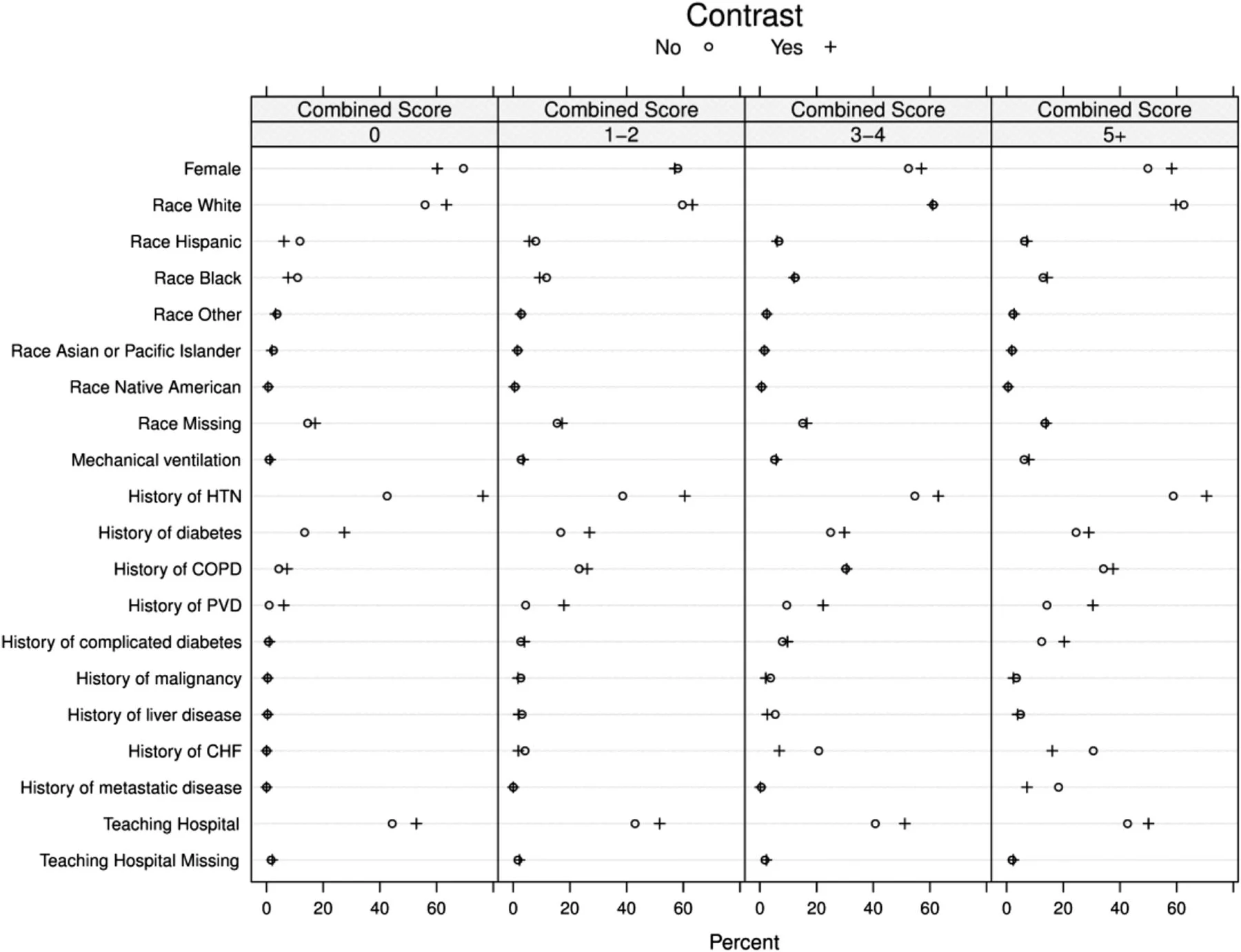

Table 1: from Wilhelm-Leen et al, JASN 2016

Primary Outcome: Primary outcome was the incidence of AKI associated with contrast administration with and without comorbidities.

Results

Not surprisingly, patients receiving contrast were older, and also more likely to be white and male. However, patients not receiving contrast had a higher comorbidity score (table 2).

Table 2: from Wilhelm-Leen et al, JASN 2016

The incidence for AKI in patients who received and did not receive contrast was 5.5% and 5.6% respectively (table 3). Contrast administration was associated with a 7.4% reduction in the odds for AKI (95% confidence interval, 0.88 to 0.97, c-statistic 0.82) adjusted for comorbidities and acuity of illness (table 3).

Table 3: from Wilhelm-Leen et al, JASN 2016

Contrast administration was associated with higher absolute risk of AKI by 2-3% in patients with infections (sepsis, pneumonia, urinary tract infection, peritonitis), COPD exacerbation and gastrointestinal bleeding. Acute pancreatitis doubled the risk.

Figure 2: from Wilhelm-Leen et al, JASN 2016

Contrast administration was associated with lower risk of AKI in patients with heart failure exacerbation, endocarditis, acute coronary syndrome, venous thromboembolism, stroke and endocarditis (figure 2, above and 3, below).

Figure 3: from Wilhelm-Leen et al, JASN 2016

The risk of AKI was higher with higher comorbidity scores in both exposed and not exposed groups to contrast (table 4). Also, the risk of AKI with contrast compared to those who did not get contrast was lower in all strata of comorbidity score except the highest.

Table 4: from Wilhelm-Leen et al, JASN 2016

Authors Conclusion

The incremental risk of AKI that can be attributed to contrast is modest at worse, and may be overestimated by physicians and overstated in the literature.

Strengths

- The study included a large and nationally representative database

- Two separate analyses stratified by disease state and logistic regression model controlled for comorbidities were performed.

Limitations

- It is a retrospective study of the administrative data that used procedure codes and diagnosis codes to identify diagnosis of acute kidney injury and administration of contrast agent, which could have been inaccurate

- There were no associated dates with procedure and diagnosis codes. Therefore the sequence of events of contrast administration and development of AKI could not be determined.

- Multiple hospitalizations for each patient could not be tracked since there were no patient identifiers.

Discussion

This study gives an insight on the incidence and risk of acute kidney injury with contrast administration in patients with and without comorbidities. Even though the study included large numbers of nationally representative populations, it had major limitations. The sequence of events of contrast administration were not determined, so we do not know if AKI occurred before or after the administration of contrast. The authors mention that they only included patients with 10-day history of hospitalization to mitigate this risk. However the bias exists and we cannot therefore establish a causal relationship between the contrast and AKI administration. Secondly, AKI diagnosis was made using ICD diagnosis codes, which increases the misclassification and information bias; and AKI could be underreported.

Most importantly, the fact that the risk of AKI was higher in patients who did not get contrast - and who had higher comorbidity scores - suggests the strong possibility of underlying selection bias. i.e. sicker patients, who were more likely to develop AKI (or already developing AKI) did not get contrast. So the control group would be enriched with patients who already had or were more likely to develop AKI, which would not get completely resolved by adjustment. This study also lumped together intravenous and intraarterial contrast - there is some suggestion that there is a difference in risk between the two groups.

This study will not change my practice of approaching risk of AKI with contrast exposure. I would continue to recommend prophylaxis with isotonic intravenous fluids to reduce the risk of contrast-induced nephropathy in my nephrology consultations and counsel patients on the risk vs. benefit of getting contrast studies.