Lancet. 2025 Oct 11;406(10512):1587-1598

doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(25)01148-1. Epub 2025 Sep 25.

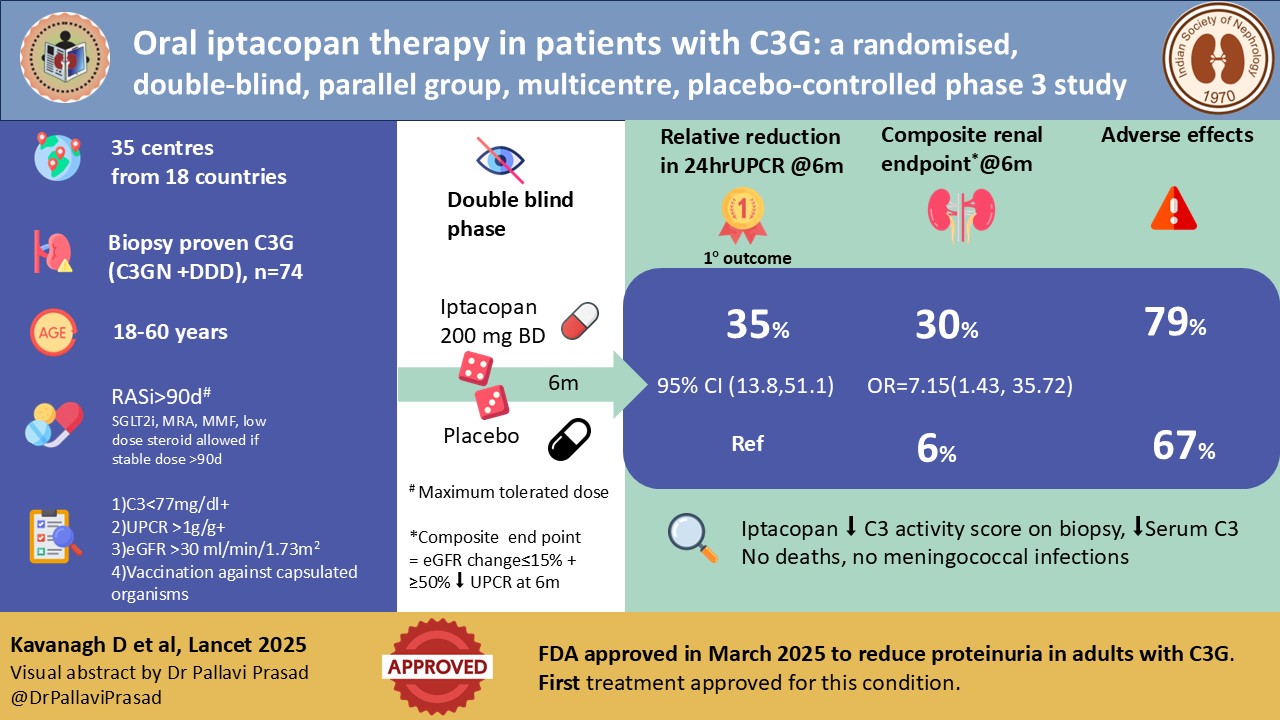

Oral iptacopan therapy in patients with C3 glomerulopathy: a randomised, double-blind, parallel group, multicentre, placebo-controlled, phase 3 study

David Kavanagh, Andrew S Bomback, Marina Vivarelli , Carla M Nester, Giuseppe Remuzzi, Ming-Hui Zhao, Edwin K S Wong, Yaqin Wang, Induja Krishnan, Imelda Schuhmann, Angelo J Trapani, Nicholas J A Webb, Matthias Meier, Rubeen K Israni, Richard J H Smith; APPEAR-C3G investigators

PMID: 41016405

Background

C3 glomerulopathy (C3G) emerged from the rubble of the old MPGN classification as an explicitly complement-driven disease rather than a purely morphologic pattern. Earlier, these patients were all labeled as MPGN type 1, 2, or 3; the reclassification into C3G and immune-complex-mediated MPGN (IC-MPGN) is based on immunofluorescence: C3-dominant deposits with little or no immunoglobulin in C3G, versus combined Ig and C3 deposits in IC-MPGN (Bomback et al, Kidney Int Rep, 2024).

Within C3G, dense deposit disease (DDD) and C3 glomerulonephritis (C3GN) are distinguished only ultrastructurally: DDD shows highly electron-dense, ribbon-like intramembranous deposits along the glomerular basement membrane, whereas C3GN features less dense, often amorphous deposits in mesangial and subendothelial locations (Bomback, et al, Kidney Int Rep, 2024; Fakhouri, et al, Kidney Int, 2020). Clinically, most patients are indistinguishable; only those with associated partial lipodystrophy or retinal drusen, more common in DDD, offer phenotypic clues (Smith et al, Nat Rev Nephrol, 2019). The recent description of apolipoprotein E enrichment in dense deposits has introduced ApoE staining as a pragmatic surrogate for electron microscopy in distinguishing DDD from other C3G patterns, particularly relevant for centers without reliable EM access (Madden et al, Kidney Int, 2024| NephJC summary). This is more than a cosmetic refinement: how we label these lesions increasingly influences trial eligibility and therapeutic decision-making. Moreover, the role of ApoE in pathogenesis of dense deposit disease is not yet known- it is possible that in the future targeted agents specific to DDD may be developed based on pathophysiology involving ApoE.

Why was this study done?

There have been limited studies on therapeutics in C3G. This stems from various reasons.

Firstly, the disease, which predominantly presents in the pediatric population and young adults, is rare, with an incidence of 1-2 new cases per million population. Secondly, the definition and understanding of this disease is constantly evolving- earlier classified as MPGN, now called C3G, and recent data showing that C3G and IC-MPGN may be a continuum of the same illness. Thirdly, the diagnostic workup of the disease includes testing for complement gene abnormalities, complement functional assays, and estimation of autoantibodies like C3Nef - tests that are not easily available in most centers (Estebanez et al, KI Reports 2024). The current standard of care consists of antiproteinuric therapy, although no randomized controlled trials have studied the effect of RASi in this disease. This is extrapolated from the role of such agents in other proteinuric renal diseases.

The KDIGO controversies conference in 2017 outlined the indications for use of immunosuppression in C3G (Figure below). Additionally, KDIGO 2021 (Rovin et al, KI 2021) suggests the use of immunosuppression in those with C3G and proteinuria >1g/day with hematuria or declining kidney function for more than 6 months. The practice points and expert opinion on the use of immunosuppression in both these KDIGO publications were based predominantly on case series and retrospective studies. Unfortunately, steroids alone do not seem to prevent kidney failure in patients with C3G (Medjeral et al, CJASN 2014; Servais et al, KI 2012). Retrospective studies show that MMF with steroids may have some role in preventing kidney failure (Awasare et al, CJASN 2018; Ravindran et al, Mayo Clin Proc 2018; Bomback et al, KI 2018; Caravaca- Fontan et al, CJASN 2020).

Recommendations for treatment of C3G from Goodship THJ et al, KI 2017

Given the central role of the complement, the first instinct was to borrow from atypical HUS and target C5 with eculizumab. Mechanistically, this leaves the alternative pathway (AP) C3 convertase untouched, C3 activation and deposits persist, while blocking only the terminal pathway and the membrane attack complex. Not surprisingly, clinical responses were limited. The first proof of concept study by Bomback et al showed a response in 3 out of 6 patients. Another single-arm trial (Ruggenenti et al) showed a partial clinical response in 3 out of 10 patients with C3G or IC MPGN when treated with eculizumab. Factor D inhibition (danicopan) likewise failed to deliver sustained AP blockade or robust efficacy signals possibly due to ineffective drug concentrations achieved in phase 2 of the drug trial (Nester et al, Am J Nephrol, 2022). These experiences were instructive: complement inhibition per se is not enough, as we need to hit the right node. In C3G, that means suppressing C3 activation and the AP amplification loop, not just its terminal effector.

With the development of agents working on the proximal alternate pathway, there emerged hope with the NOBLE (Bomback et al, KI Reports 2024) and DISCOVERY (Dixon et al, KI Reports 2023) trials, which showed the effect of iptacopan and pegcetacoplan, respectively, in C3G. The APPEAR C3G trial was the first double blind phase 3 RCT of a complement inhibitor therapy in C3G.

Complement-directed drugs for C3G from Estebanez et al, KIR 2023

The Study

The APPEAR C3G trial was a double blind, multicentre, placebo-controlled RCT funded and designed by Novartis which enrolled 74 patients from 35 centres across 18 countries and randomized them 1:1 to iptacopan 200 mg bd vs placebo. Randomization was stratified by treatment with corticosteroids, mycophenolic acid, or both (yes or no). It consisted of a 90-day screening and run-in period, 6 months double blind treatment period, and 6 months of open-label extension, where both arms were treated with iptacopan.

The trial included adult (18-60 years) native kidney biopsy-proven patients with C3G (C3GN or DDD) with low C3 level <77 mg/dl and eGFR >30 ml/min/1.73m2 with 24 h UPCR >1g/g. Patients were required to be vaccinated against Neisseria meningitidis and Streptococcus pneumoniae. Key exclusions included IFTA >50% on biopsy, rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis, evidence of monoclonal gammopathy, active or past infection considered to be responsible for the disease, prior kidney transplantation, and the use of immunosuppressants (apart from prednisolone equivalent >7.5 mg/day or mycophenolate mofetil). All patients were required to be on the maximal recommended or tolerated dose of ACE/ARB for a stable dose for >90 days. Immunosuppression, if present, should have been on a stable dose for >90 days.

Outcomes

The primary efficacy endpoint was the change in 24 hr UPCR at 6 months.

Key secondary efficacy endpoints included:

percentage of patients reaching a composite renal endpoint (≤15% change in eGFR + ≥50% decrease in UPCR),

change in eGFR at 6 months,

change in FACIT fatigue score

effect of iptacopan on the change in histological activity score at 6 months.

Exploratory outcomes included the change in serum C3, change from baseline in glomerular C3 deposit and total chronicity scores from a renal biopsy at 6 months, and the effect of the drug on plasma and urinary complement biomarkers.

The trial had a rigorous pre-screen period with the requirement of confirmation of eGFR and proteinuria at day -15 apart from the initial screening tests. The study included a mandatory day -45 biopsy to assess histological scores and exclude IFTA >50% and protocol biopsies at day 180 and preferably at Day 360.

What did they find?

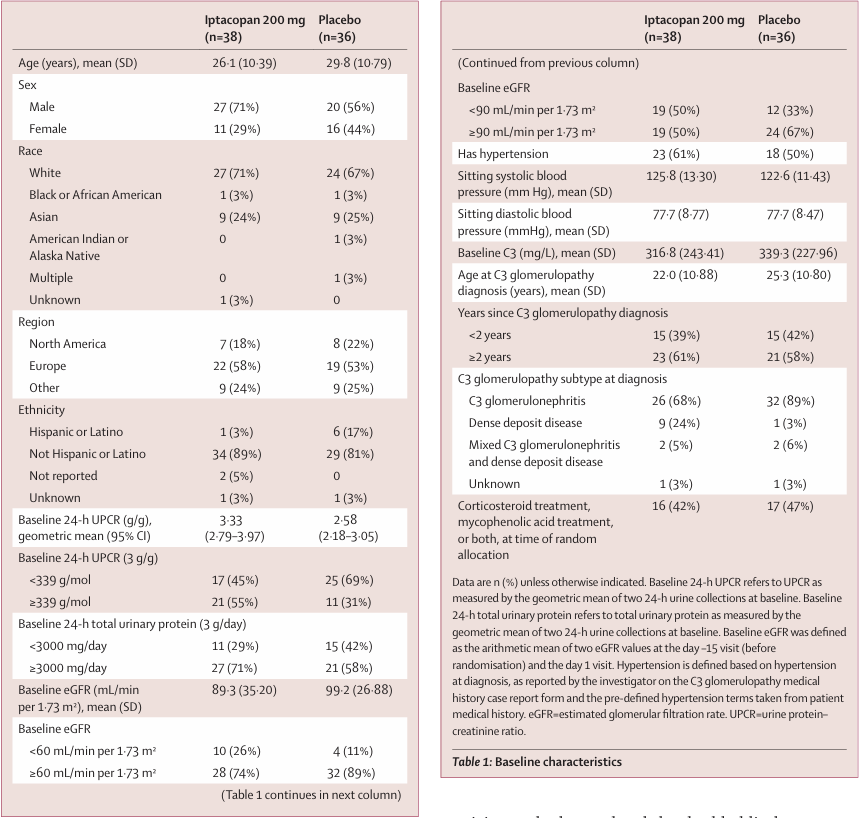

132 participants were screened, and 56% (n=74) were randomised 1:1 to iptacopan versus placebo. The mean age was 27.9 years, 64% were male, and 69% white. Mean eGFR was lower, and 24 hr UPCR was higher in the iptacopan group at baseline. 99% of patients were on RAS blockers and 45% on immunosuppressants at the time of randomization.

Table 1 from Kavanagh et al, Lancet 2025

Efficacy

Proteinuria

Iptacopan met the primary endpoint: a 35.1% relative reduction in 24-hour UPCR vs placebo at 6 months (95% CI 13.8-5.11; p= 0.0014). In the iptacopan arm, geometric mean UPCR fell from 3.33 g/g at baseline to 2.17 g/g (-30.2%, 95%CI -42.8 to -14.8). In the placebo arm, UPCR rose from 2.58 g/g to 2.8 g/g (+7.6%, 95% CI 11.9 to 31.3)

Figure 2. Percentage change in proteinuria (24-h UPCR) following treatment of iptacopan or placebo relative to baseline at 6 months (A) and up to 12 months (B), from Kavanagh et al, Lancet 2025

Roughly 30% of iptacopan-treated patients achieved ≥ 50% reduction in proteinuria at 26 weeks, versus about 6% on placebo.

Complement biomarkers and histology (fig 5)

Serum C3 increased rapidly and substantially in the iptacopan group, with a geometric mean of approximately. 3-fold rise at 12 months; similar normalization occurred in the former placebo group after crossover at 6 months. Plasma and urinary sC5B-9 levels fell, indicating downstream dampening of terminal pathway activation despite targeting factor B. Repeat biopsies showed reduced glomerular C3 deposition and improvements in histologic activity scores, particularly endocapillary proliferation and leukocyte infiltration, although numbers were small and changes modest.

Kidney function

At 26 weeks, the mean change in eGFR was numerically better with iptacopan but did not reach statistical significance vs placebo in the conventional between-group comparison. However, when historical pre-treatment eGFR slopes (up to 2 years before enrollment) were compared to the on-treatment slopes, iptacopan shifted the mean annual eGFR trajectory from a decline of - 10.8 mL/min/1.72m2 per year to essentially flat (-0.03 mL/min/1.72m2). Meanwhile the placebo group also improved(-7.64 to -3.8 ml/min/1.73m2), but to a lesser degree- this could possibly be due to better blood pressure control and a closer follow up during the trial period.

Figure 4. (A) Model estimated mean change from baseline (±SE) of eGFR by treatment up to month 12. (B) Annualised eGFR slope change for all patients, from Kavanagh et al, Lancet 2025

Durability

Open-label extension analyses show that proteinuria reduction and complement biomarker improvements are generally maintained upto 12 months of iptacopan therapy.

Safety

Treatment-emergent adverse events occurred in 79% of iptacopan vs 67% of placebo recipients; most were mild or moderate. Serious adverse events were infrequent (8 vs 3%), with no deaths, no discontinuations because of treatment-emergent events, and no meningococcal infections.

One notable nuance: infections by encapsulated bacteria did occur rarely in iptacopan-treated patients across the development program (e.g. S. pneumoniae bacteremia), reinforcing that vaccination and vigilance remain essential even if the observed risk is modest.

Table 2. Adverse events during double-blind treatment period, from Kavanagh et al, Lancet 2025

What does the study add?

APPEAR-C3G is the first positive phase 3 trial in C3G, crystallizing several important shifts in how we should think about and treat complement-mediated glomerular disease.

Proof that “hitting the engine” of the alternative pathway translates into clinical benefit

The trial provides rigorous, randomized evidence that targeting factor B (central to AP C3 convertase) can simultaneously:

normalize or markedly improve systemic complement activity (serum C3, sC5b-9)

reduce glomerular C3 deposition and histologic activity, and

lower proteinuria and flattened eGFR decline.

This coherence across mechanism, biomarkers, histology, and clinical surrogates is qualitatively different from what anti-C5 or factor D blockade achieved in C3G.

Although meaningful, not maximal effect on proteinuria

The 35.1% relative reduction vs placebo and ∼30% absolute mean reduction in UPCR are clearly clinically relevant, especially in a disease where even modest reductions in proteinuria correlate with slower progression. However, the magnitude of the effect is smaller than that seen with C3 inhibitor pegcetacoplan in VALIANT, which delivered 68.1% relative reduction in UPCR and ≥ 50% proteinuria reduction in ∼60% treated patients across C3G and primary IC-MPGN (Fakhouri et al. NEJM 2025| NephJC summary).

Cross-trial comparisons must be cautious- different populations, endpoints, and disease mixes- but the signal is consistent: C3-level blockade tends to produce deeper antiproteinuric responses than factor B inhibition, at the likely cost of more global complement suppression.

Clinically, APPEAR-C3G positions iptacopan as a drug that will move many patients from “high-risk” to moderate proteinuria, but not necessarily into full remission. For some, especially those starting with UPCR in the 1-3 g/g range and relatively preserved eGFR, that may be sufficient to meaningfully shift long-term risk. For those with massive nephrotic-range proteinuria or rapid decline, we may ultimately favor C3 inhibition, or sequential strategies, if safety and access allow.

A “best-case” population, and generalizability question

APPEAR-C3G enrolled adults with native-kidney C3G, eGFR ≥ 30 ml/min/1.73m2, low serum C3, and without rapidly progressive crescentic disease or very advanced chronic damage. In addition, nearly 70% were White, and more than half were from Europe. This matters because:

Many real-world C3G patients have normal serum C3 despite clear tissue-level AP activation. The authors note, and the mechanism strongly suggests, that iptacopan should still work in these patients, but APPEAR-C3G doesn’t explicitly prove this.

Pediatric C3G, where the lifetime risk of progression is greatest, is not represented here; adolescent and IC-MPGN cohorts are still under study.

Patients with eGFR <30ml/min/1.73m2 or heavy chronic scarring were largely excluded. Whether iptacopan can alter the trajectory in late-stage disease is unknown.

Rethinking the role of background immunosuppression

A prespecified analysis (reported in the broader development program) suggests iptacopan’s proteinuria-lowering effect is attenuated in patients already on MMF or steroids at baseline: roughly a 14.5% relative reduction vs placebo in that group, compared with 47.5% in those not on immunosuppression.

This raises important, and uncomfortable, questions:

Are we simply seeing that immunosuppressed patients have more refractory, inflamed, or chronically scarred disease?

Or does persistent broad immunosuppression blunt some of the measurable benefit of targeted complement blockade on proteinuria, perhaps by having already maximally reduced the inflammatory component?

Either way, APPEAR-C3G strengthens the emerging view that complement inhibitors should not just be added on top of indefinite MMF and steroids, but may increasingly replace them as the backbone of long-term disease control- reserving classical immunosuppression for short induction in truly rapidly progressive or crescentic cases (Kavanagh et al, KI reports, 2026)

Safety and the real meaning of “acceptable risk”

The absence of meningococcal infections in APPEAR-C3G is comforting but should not breed complacency. The trial is small, follow-up is 12 months, and all patients were vaccinated. Experience from genetic complement deficiencies and from C5 blockade tells us that sustained perturbation of the cascade increases susceptibility to encapsulated bacteria.

Here, iptacopan’s mechanistic selectivity is an advantage: the classical and lectin pathways remain capable of forming C3 convertases, preserving some opsonization and defense against common pathogens, in contrast to global C3 blockade. (Kavanagh et al, KI reports, 2026) But “lower risk than a C3 inhibitor” is not “no risk”. In practice, vaccination, patient education, and a low threshold for early antibiotic therapy remain non-negotiable; some patients may reasonably warrant prophylaxis in the early months of treatment.

New questions that APPEAR-C3G forces us to confront

APPEAR-C3G convincingly answers if proximal AP inhibition can modify C3G biology and surrogate outcomes. It doesn’t yet answer:

How much complement inhibition is enough? The degree of C3 suppression and C3 staining clearance required to secure long-term kidney survival is unknown.

How long should we treat? Given that most drivers of AP overactivation (genetic variants, autoantibodies) are chronic, complement blockade may need to be long-term or even indefinite in many patients. But structured withdrawal studies- analogous to those in atypical HUS- are needed to define who can safely stop.

How can we choose and sequence agents? With inhibitors of factor B and C3 now both available (and others coming), we will have to decide: start with iptacopan and escalate to C3 inhibition in partial responders? Should we reserve pegcetacoplan for those with mixed C3G/IC-MPGN biology or transplant.

Conclusion

APPEAR-C3G marks a decisive break with the era of empiricism in C3G. It shows that if you intervene at the level where the alternative pathway actually misfires factor B- you can produce coherent improvements across complement biology, kidney histology, proteinuria, and eGFR slope, with a safety profile that is acceptable in the context of a disease otherwise marching many young patients toward kidney failure.

The study should change practice, but not shut down our critical thinking. Iptacopan is a powerful new tool, not the final answer. How we position it relative to pegcetacoplan, how early we start it, how long we continue it, and in whom we dare to stop it,will collectively determine whether APPEAR-C3G is remembered as the cornerstone of rational complement therapeutics in C3G, or just the first step.