#NephJC Chat

Tuesday May 24th, 2022 at 9 pm Eastern

Wednesday May 25th, 2022 at 9 pm Indian Standard Time, 4:30 pm BST

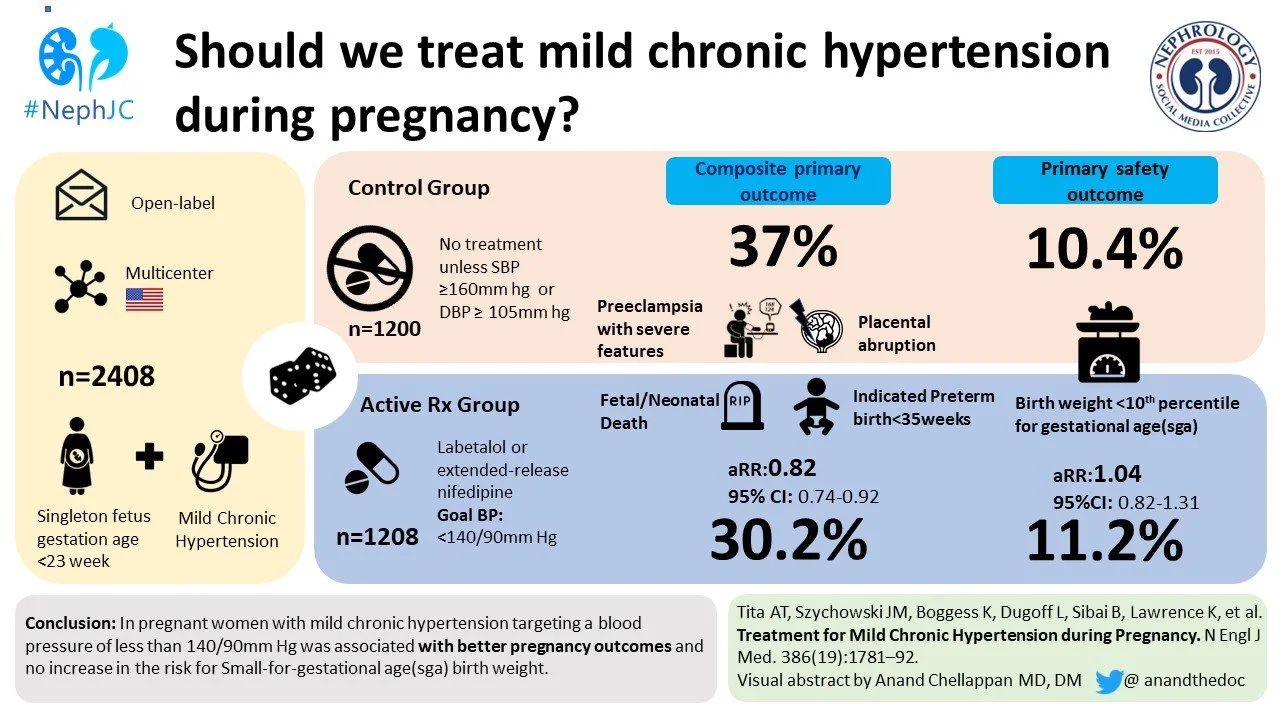

N Engl J Med. 2022 May 12;386(19):1781-1792.Doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2201295. Epub 2022 Apr 2.

Treatment for Mild Chronic Hypertension during Pregnancy

Alan T Tita, Jeff M Szychowski, Kim Boggess, Lorraine Dugoff, Baha Sibai, Kirsten Lawrence, Brenna L Hughes, Joseph Bell, Kjersti Aagaard, Rodney K Edwards, Kelly Gibson, David M Haas, Lauren Plante, Torri Metz, Brian Casey, Sean Esplin, Sherri Longo, Matthew Hoffman, George R Saade, Kara K Hoppe, Janelle Foroutan, Methodius Tuuli, Michelle Y Owens, Hyagriv N Simhan, Heather Frey, Todd Rosen, Anna Palatnik, Susan Baker, Phyllis August, Uma M Reddy, Wendy Kinzler, Emily Su, Iris Krishna, Nicki Nguyen, Mary E Norton, Daniel Skupski, Yasser Y El-Sayed, Dotum Ogunyemi, Zorina S Galis, Lorie Harper 1, Namasivayam Ambalavanan, Nancy L Geller, Suzanne Oparil, Gary R Cutter, William W Andrews; Chronic Hypertension and Pregnancy (CHAP) Trial Consortium

PMID: 35363951

Introduction

Given there will be more than 40 babies born worldwide by the time you finish reading this sentence, it is distressing that we still don't know what maternal blood pressure we should target. The evidence base is weak and conflicting, and therefore international guidelines vary widely (Figure 1). This becomes more mind-boggling when you realize that the incidence of hypertension in pregnancy has been steadily increasing (Ananth et al. Hypertension. 2019;74:1089–1095) & and is associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes (Bateman et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2012; 206:134.e1).

Figure 1: Summary of published guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of hypertension during pregnancy. From Garovic et al, Hypertension 2021.

In nephrology, we are watching blood pressure (BP) targets go lower and lower in a post-SPRINT world, but when patients are pregnant there is concern that lower targets could mean lower placental blood flow and cause adverse fetal outcomes. In addition, there’s been little evidence favoring active management of mild-to-moderate hypertension to protect maternal health in pregnancy. A 2018 Cochrane review of 31 randomized trials and 3,485 women looked at drug-treatment versus placebo or no-drug-treatment for mild-to-moderate hypertension, and did not demonstrate any protective effect for active treatment to prevent preeclampsia (Abalos et al, Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2001). A randomized controlled trial that enrolled 987 pregnant subjects who were randomized to less-tight control of blood pressure (target diastolic BP < 100 mmHg) versus tight control (target diastolic BP < 85 mmHg) also showed no significant between-group differences in the risk of pregnancy loss, high-level neonatal care, or overall maternal complications. (Magee LA et al. N Engl J Med 2015;372:407-417).

This was reviewed in an early edition of NephMadness (2015!)

The current study was planned prior to this publication and set out to be the largest RCT on the issue, specifically testing whether the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) guidance (Figure 1) was effective and safe.

The Study

Design

The Chronic Hypertension and Pregnancy (CHAP) Trial was a multicenter, pragmatic, open-label, randomized, controlled trial, conducted across 61 sites in the US.

Inclusion Criteria:

Pregnant women with a singleton pregnancy at < 23 weeks gestation

AND

New-onset chronic hypertension

or

Known chronic hypertension, if their BP at enrollment was >140/90

Patients without known hypertension who had elevated BP of 140/90 or higher on 2 separate occasions at least 4 hours apart were considered to have new-onset chronic hypertension. Anyone with documented elevated blood pressure in the past with previous or current use of antihypertensive therapy was considered to have known chronic hypertension.

The exclusion criteria were as follows:

Severe hypertension (>160/105)

Treatment with >1 antihypertensive at baseline

Known secondary hypertension

Multiple fetuses

High-risk comorbidities for which treatment may be indicated (e.g. diabetes mellitus with complications, CKD), cardiomyopathy, angina, CAD, prior stroke, retinopathy, sickle cell disease)

Obstetric complications that increased fetal risk

Contraindications to the use of first-line antihypertensive medications in pregnancy (e.g. known hypersensitivity to labetalol and nifedipine)

Current substance abuse or addiction

Eligible patients were randomized 1:1 into two groups:

Active Treatment - blood pressure goal <140/90 mmHg

Control - antihypertensive agents stopped at randomization, suspension continued unless severe hypertension developed (SBP ≥160 mmHg or DBP ≥105 mmHg)

Interestingly, the paper gives a goal of <140/90 for the control group if treatment becomes required for severe hypertension, but the supplementary materials states the goal was <160/105 mmHg (Supp appendix, p 11)

We know how important it is to accurately measure blood pressure, and the research staff provided training sessions, video teaching and then refreshers for the clinical staff tasked with taking the measurements, as well as remedial coaching as targeted by quality control monitoring. Staff were trained to include appropriate patient positioning, use of correct cuff size, appropriate waiting period of 5 minutes of rest prior to taking blood pressure, and to repeat blood pressure once more if initial SBP ≥ 140 and/or DBP ≥ 90 mmHg.

The first-line antihypertensives recommended were labetalol or extended-release nifedipine, though amlodipine or methyl-dopa were also acceptable according to patient/prescriber preference. Follow up visits were scheduled every 1-4 weeks based on the patient’s gestational-age and practices at the local center, at the discretion of the clinician. Antihypertensive dose was escalated to the maximum tolerated dose if target blood pressure was not achieved. The investigators examined adherence by using techniques such as questionnaires, interviews, and pill counting at each visit and before making any adjustments to the regimen.

Outcomes

The primary efficacy outcome was a composite of fetal or neonatal death, preeclampsia with severe features, medically indicated preterm birth before 35 weeks gestation, or placental abruption.

Preeclampsia with severe features was defined as:

Worsening hypertension ≥160/110 after 20 weeks’ gestation AND proteinuria,

OR

Worsening hypertension above prior baseline (≥140/90) without proteinuria AND one or more of the following:

Cerebral symptoms (including seizures or persistent headaches) or persistent visual symptoms

Thrombocytopenia <100K/µL

Creatinine > 1.2 mg/dL (or doubling from baseline)

2-fold elevated liver enzymes, HELLP syndrome, or persistent RUQ pain

Pulmonary edema (including oxygen desaturation < 90% requiring treatment with diuretics and oxygen)

The primary outcome was assessed in five pre-specified subgroups:

hypertension treatment status at baseline (newly diagnosed, diagnosed and receiving medication, or diagnosed but not receiving medication)

race or ethnic group (as reported by the patient or abstracted from records)

diabetes status

gestational age at enrollment

body-mass index

Poor fetal growth, defined as a birth weight measuring less than the 10th percentile for gestational age and infant sex, was the primary safety outcome. Data on various secondary outcomes was also obtained.

Secondary outcomes included maternal death or serious complications, preterm birth, and newborn/neonatal outcomes.

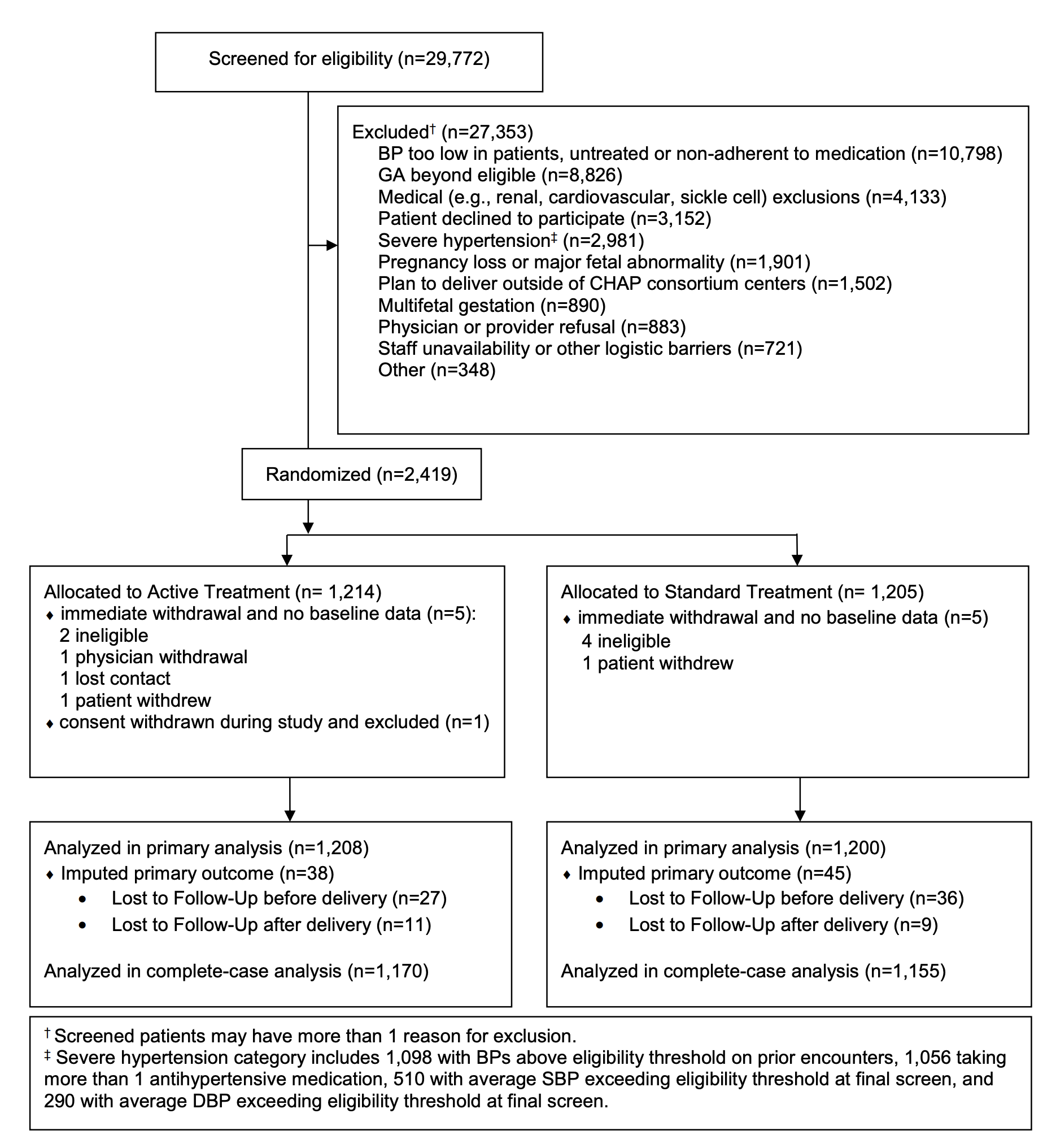

The original plan was to enroll 4,700 patients, which was based on the assumption of an approximate incidence of 16% in primary outcome events. However, a blinded assessment done after enrollment of initial 800 patients revealed that the incidence was at least 30%, after which it was determined that a sample size of 2,404 patients would be sufficient to detect relative effect sizes of 25% or more (which was adjusted down from a previous threshold of a 33% effect size).

Results

A total of 29,772 women were screened, out of which 2,419 were randomized. However, 11 patients were removed from the initial sample before recording any data, yielding a final sample size of 2,408. 1,208 were randomized to the treatment group and 1,200 to the control group.

Figure 2: Consort diagram from Supplementary Appendix of Tita et al, NEJM 2022.

The baseline characteristics of the two groups are shown in Table 1; more than half in each group (56%) had chronic hypertension and were already on antihypertensive medications, while 22% had known hypertension but were not taking medications; the rest (22%) were newly diagnosed. More than 16% of patients had diabetes, and more than 75% of patients in both cohorts had a BMI > 30. Black women constituted 48% of study participants.

Table 1: Characteristics of patients at baseline. From Tita et al, NEJM 2022.

Almost everyone who was treated, was treated with labetalol or nifedipine.

Table S4: Antihypertensive use at last blood pressure visit. From Supplementary Appendix of Tita et al, NEJM 2022.

Mean BP in the active treatment group was 129.5/79.1 mmHg vs 132.6/81.5 mmHg in the standard treatment group, for a difference of 3.1 mmHg in the systolic BP and 2.3 mmHg in the diastolic BP. The absolute difference in the BP wasn’t large, particularly at the end of the study, however Figure 3 below depicts that significant separation was achieved during the middle of the study. Also, note from Table S4 above that 88.9% patients in the active treatment group were receiving antihypertensive medications, as opposed to only 24.4% patients in the control group.

Figure 3: Mean blood pressure through the study period. From Tita et al, NEJM 2022.

Primary Outcome

A primary outcome event occurred in 30% patients in the active-treatment group, as opposed to 37% patients in the control group; adjusted risk ratio (aRR) for a primary outcome was 0.82 (95% confidence interval 0.73 to 0.92, p < 0.001), with a number-needed-to-treat (NNT) of 14.7.

Table 2: Primary and safety outcomes. From Tita et al, NEJM 2022.

The safety outcome was statistically not significant: 11.2% of newborns in the treatment group were under the 10th percentile of their gestational age, as opposed to 10.4% in the control group. The risk ratio similarly was not significant for newborns with reported birth weight of < 5th percentile. Analyses across the pre-specified subgroups were consistent with the overall results (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Risk of primary outcome in pre-specified subgroups. From Tita et al, NEJM 2022.

Secondary Outcomes

Secondary maternal outcomes (Table 3), including the composite cardiovascular complications, severe hypertension plus proteinuria, and incidence of cesarean delivery, did not differ significantly. However, the incidence of severe hypertension was significantly less in the active-treatment group versus control (36.1% vs 44.3%, respectively). Hypertension with end-organ damage was also lower in the active-treatment group (11.3% vs 15.1%), albeit hypertension with proteinuria was categorized separately which favored active-treatment group, but did not reach statistical significance.

Table 3: Maternal Outcomes. From Tita et al, NEJM 2022.

Neonatal outcomes, including the composite of severe neonatal complications, placental weight, bradycardia, and hypotension, did not differ significantly. Preterm births were significantly less in the active-treatment group (27.5% vs 31.4%) (Table 4).

Table 4: Neonatal Outcomes. From Tita et al, NEJM 2022.

Discussion

This trial addressed an important question and knowledge gap: is active treatment of mild-to-moderate hypertension in pregnancy safe for the fetus, and does it have any beneficial effects? And it showed that the answer to both, for the most part, is YES! Women in whom moderate hypertension was actively treated had lower incidence of primary outcome events including severe preeclampsia, premature birth, placental abruption or fetal or neonatal death.

Overall, it was a well-done trial with a large sample size and was conducted at 61 sites all over the US. For comparison, the Cochrane review that we mentioned earlier looked at 31 randomized trials, which had a combined sample size of 3485 patients. The CHAP trial alone had more than 2400 patients! Additionally, the high proportion of black and hispanic females included in the trial make the results generalizable across to patients of diverse backgrounds.

Looking at the inclusion criteria one does worry a patient with known chronic hypertension on one antihypertensive medication could come into the study with a systolic BP of, say, 155 mmHg (already not showing the usual dip in pregnancy), and then have their one antihypertensive stopped. Though this falls within the ACOG guidance at the time, it does look like a potential recipe for disaster. Indeed, in the sub-group analysis in Figure 2, it does appear that this “diagnosed, receiving medication” group drives the overall study outcome.

An important limitation to the generalizability of the study to the real world is that in the majority of settings BP measurement is not obtained following the standardized protocols with adequate rest time and training for staff. We’ve been here before when we discussed the 120 mmHg systolic target for patients with CKD - though we all agree how we should ideally be measuring BP, sadly in the office and on the wards, inconsistent measurement techniques persist due to resource constraints and lack of training.

Another thing that questions the quality of the study is the fact that the investigators failed to predict the incidence of the primary outcome event accurately; the incidence of 30% which was obtained after an initial blinded assessment was almost double that of the predicted outcome. This eventually led to a decrease in the required sample size. At the same time, they also decided to look for an effect size of 24% instead of previously decided 33%. The authors do not explain as to why the estimated and observed event rate are so different, and also we are unable to find any explanation for change in the effect size that they were looking for - so this is anybody’s guess. Lastly, as mentioned previously, there is a discrepancy between the target blood pressure goal if any patient in the control group developed severe hypertension; the paper mentions that their goal BP with treatment was <140/90, however in the supplemental material it states the goal BP was < 160/105.

One last thing to keep in mind regarding the study is that this study does not provide a target blood pressure for pregnant females with mild hypertension and without other major comorbidities, but rather offers a threshold at which to offer therapy (>140/90 mmHg). The mean difference between the treatment groups was small at 3.1 mmHg systolic, but the separation in proportions of women on an antihypertensive was substantial, and the results show this was sufficient to provide a clinically meaningful benefit.

Conclusion

Undoubtedly, this is one of those studies which can be classed as ’practice changing’, despite its limitations. It has filled an important knowledge gap, showing that active treatment of mild-to-moderate hypertension in pregnancy is safe for the fetus and beneficial for the mother. The American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology should be commended for providing a prompt Practice Advisory for the integration of findings from this well-done trial into immediate clinical practice, newly recommending BP of 140/90 mmHg as a threshold for initiation (or titration) of antihypertensive therapy.

Summary prepared by Bilal Sheikh

Shaukat Khanum Memorial Cancer Hospital, Lahore, Pakistan

NSMC Intern, Class of 2022

Reviewed by Jamie Willows and Jade Teakell