#NephJC Chat

Tuesday January 11th, 2022 at 9 pm Eastern Standard Time

Wednesday January 12th, 2022 at 9 pm Indian Standard Time

J Am Soc Nephrol. 2022 Jan; 33(1): 238-252. doi:10.1681/ASN.2021060794. Epub 2021 Nov 3..

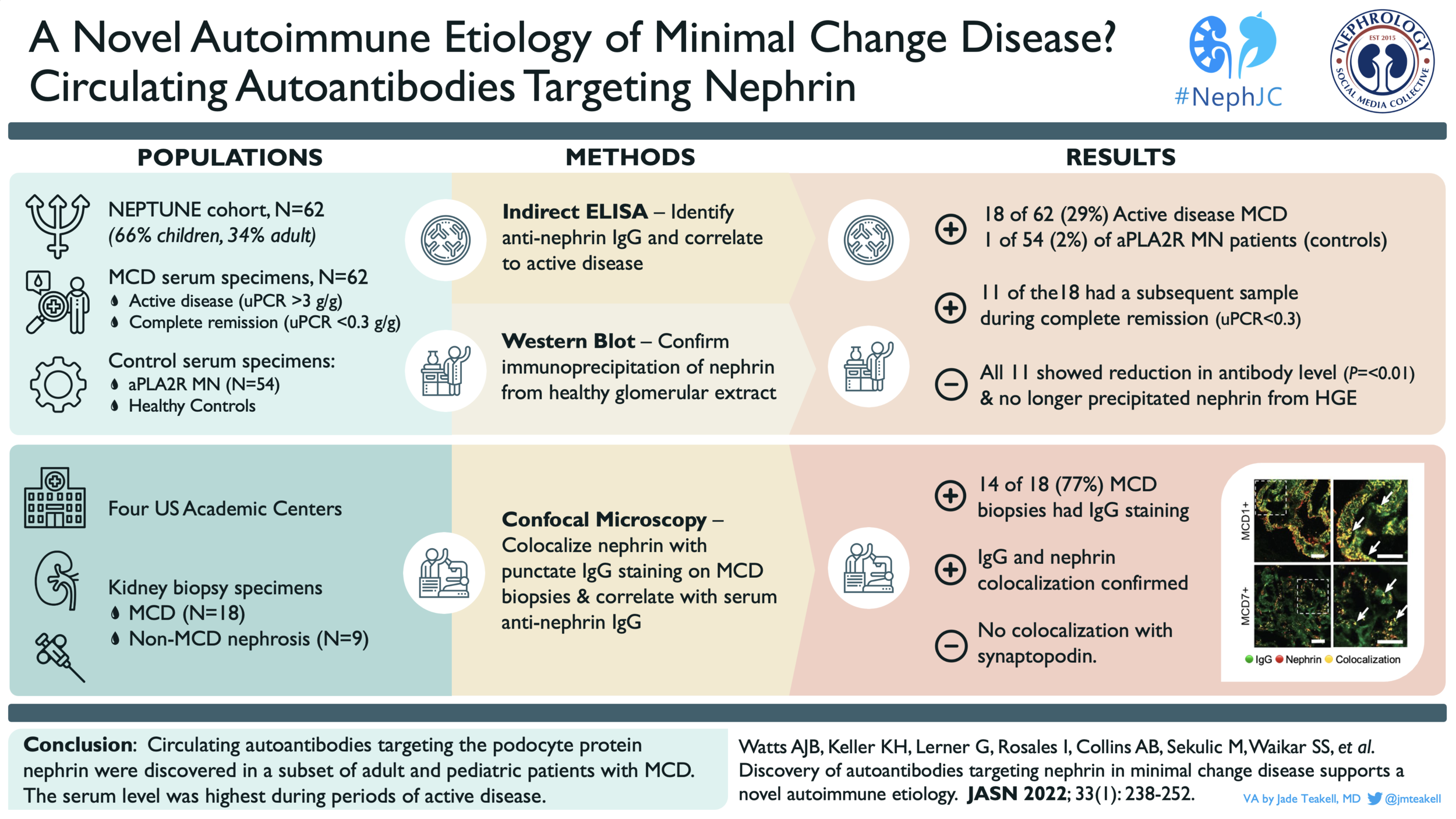

Discovery of Autoantibodies Targeting Nephrin in Minimal Change Disease Supports a Novel Autoimmune Etiology.

Andrew J.B. Watts, Keith H. Keller, Gabriel Lerner, Ivy Rosales, A. Bernard Collins, Miroslav Sekulic, Sushrut S. Waikar, Anil Chandraker, Leonardo V. Riella, Mariam P. Alexander, Jonathan P. Troost, Junbo Chen, Damian Fermin, Jennifer L. Yee, Matthew G. Sampson, Laurence H. Beck, Joel M. Henderson, Anna Greka, Helmut G. Rennke, and Astrid Weins.

PMID: 34732507

Introduction

In 1827 Richard Bright described an “uncoupling of kidney secretions'' by which “protein was lost in the urine water.” Bright’s test for the presence of albuminuria was heat coagulation – urine placed in an iron spoon was held over a candle, and when albumin was present, white streaks would appear. In his early case reports, he focused on the correlation of three phenomena, namely the presence of dropsy, albuminous urine, and depictable pathologic changes in the kidneys. (Keith, AMA Arch Intern Med 1954). (For those not up-to-date on 19th century medical terminology, “dropsy” was a catch-all term for many conditions that caused generalized edema, including nephrotic syndrome). As we now know, nephrotic syndrome (NS) comprises heavy proteinuria, hypoalbuminemia, and peripheral edema.

Minimal change disease (MCD), or diffuse podocytopathy with minimal changes, is the cause of nephrotic syndrome in 70-90% of children and 10-15% of adults (Vivarelli, CJASN 2017; Waldman, CJASN 2007). Classically, kidney biopsies from patients with MCD show normal glomeruli on light microscopy and negative immunofluorescence (IF), but have extensive glomerular podocyte foot process remodeling (effacement) without dense deposits on electron microscopy (EM).

There is debate on whether MCD and focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS) represent a spectrum of the same process or two distinct entities. As in an improv comedy class, the answer in this debate may be more of a “Yes, and…” In a 2018 NephJC commentary, Michelle Rheault described how recognizing outliers can guide clinicians and researchers. For example, rare cases of congenital nephrotic syndrome (e.g. “congenital nephrotic syndrome of the Finnish type” or CNF, which was first described in the 1950s) did not respond to treatment in the same way that “typical MCD” did. It wasn’t until 1998, that a gene mutation in NPHS1 that encodes the protein nephrin was identified as the cause of CNF (Kestilä, Mol Cell 1998). Nephrin is an essential structural component of the podocyte slit-diaphragms, and the severe proteinuria in MCD is now understood to result from disruption of the slit-diaphragm protein complexes that link the interdigitating foot processes of glomerular podocytes (Image 1). However, outside of genetic mutations in NPHS1, the exact process(es) causing this damage in pediatric and adult MCD has remained elusive.

Image 1, from Lennon, Front Endocrinol 2014: The molecular components of glomerular podocyte slit-diaphragms.

Previous work hinted that MCD might be caused by an antibody-mediated autoimmune process. Biopsy samples from patients with MCD typically have no complement or immunoglobulin deposits on IF microscopy; however, in a small subset of MCD patients, a subtle puntate IgG staining pattern (Image 2) has been observed (D’Agati VD, Atlas of Nontumor Pathology 2005). Additionally, observations that B-cell targeted therapies are effective in children and adults with relapsing or steroid-dependent MCD suggest a pathogenic role for circulating antibodies (Basu, JAMA Ped 2014; Fenoglio, Oncotarget 2018). Finally, antibodies against nephrin have been shown to induce massive proteinuria in animal models (Orikasa J Immunol 1988; Takeuchi, Nephron 2018) and have been identified after kidney transplant in patients with CNF who again develop proteinuria. The presence of a circulating factor that could increase glomerular membrane protein permeability has been hypothesized since the 1970s (Maas, NDT 2014), and it seems plausible that anti-nephrin antibodies could be a cause of MCD or an MCD-like disease in native kidneys.

Image 2, from Rennke HG, 2018 GlomCon Presentation: Example of a MCD biopsy that is IF negative but for a “fine dusting of IgG” over the podocytes.

Key Questions for the Study

Can anti-nephrin antibodies be identified in the serum of patients with MCD?

Do anti-nephrin antibodies correlate with MCD activity?

Do anti-nephrin antibodies colocalize with IgG staining pattern found in a subset of MCD biopsies?

The Study

Design/Methods

Observational Study, Clinical Research, Translational Research

Clinical samples

Evaluation of plasma/serum samples for presence of nephrin auto-antibodies

Indirect ELISA

Immunoprecipitation (and identification by Western blot) of the full-length nephrin protein from healthy glomerular extracts (HGE) or of the recombinant extracellular domain of human nephrin

Inspection of kidney biopsy tissue for podocyte-associated punctate IgG lesions that colocalize with nephrin

Confocal Microscopy, Immunofluorescence

Study population

Adult and pediatric patients with biopsy-proven MCD

Nephrotic Syndrome Study Network (NEPTUNE)

Serum samples

Four Institutions - Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston Medical Center and the Mayo Clinic Kidney Disease Biobank

Serum samples, biopsy tissue

Healthy controls

Partners Healthcare Biobank

MCD status definitions

Active disease = urine protein to creatinine ratio (uPCR) > 3 g/g

Complete remission (CR) = uPCR < 0.3 g/g

Partial remission (PR) = more than 50% reduction in proteinuria

Relapse = uPCR increased to >3 g/g after CR

Steroid-dependent = steroid-sensitive nephrotic syndrome with 2 or more relapses during tapering or within 14 days of stopping steroids

Funding

The authors and this clinical/translational research project were supported by several sources including NIH Training Fellowships, Harvard Medical School’s Eleanor Miles Shore Fellowship, NIH/NIDDK grants, NIH NEPTUNE Consortium, University of Michigan, NephCure Kidney International, and Halpin Foundation

Results

From the NEPTUNE cohort, a group of 62 patients (41 adults and 21 children) with biopsy-proven MCD were identified. These patients were selected, in part, due to availability of serum samples from before (active disease) and after treatment; serum samples from after treatment were taken from patients in either complete or partial remission. A group of 54 patients with membranous nephropathy positive for anti-PLA2R antibodies and a group of 30 healthy controls were used for comparison. The authors developed and used an indirect ELISA to identify nephrin-targeting autoantibodies in serum samples. The maximum detected level in the healthy controls was used as the positivity threshold (dotted line in Figure 1A). The specificity of these antibodies for nephrin was confirmed by their ability to precipitate nephrin specifically from healthy glomerular extract (HGE). The demographic and clinical information on the 62 patients with MCD is outlined in Table 1.

Table 1 from Watts et al. JASN 2022: Demographic and clinical data of the patients from the NEPTUNE cohort, grouped by anti-nephrin antibody status.

Of the 62 MCD samples from the period of active disease (uPCR >3 g/g), 18 (29%) were positive for anti-nephrin antibodies. In the anti-PLA2R+ group, anti-nephrin antibodies were detected in only 1 sample, suggesting that these antibodies are not a general feature of glomerular disease (Figure 1A). A subsequent serum sample (obtained during complete or partial remission) was available for 11 of the 18 patients who had MCD and were positive for anti-nephrin antibodies during their active disease. During remission, complete absence of or significant reduction in anti-nephrin antibodies was observed (Figure 1B) as well as loss of ability to immunoprecipitate nephrin from HGE (Figure 1C).

Figure 1 from Watts et al. JASN 2022: Anti-nephrin antibody levels detected in the cohorts (A); comparison of anti-nephrin antibody levels (B) and nephrin immunoprecipitation (C) in states of active disease vs. remission.

Next, the authors tried to determine if there were clinical differences between the clinical course of MCD with anti-nephrin antibodies and MCD without anti-nephrin antibodies. The median elapsed time from diagnosis to complete remission between the anti-nephrin antibody positive (4.4 months) and negative (5.4 months) groups was similar (P=0.72) (Figure 2A). The relapse-free period appears shorter in patients with anti-nephrin antibodies (6 months) than in patients without anti-nephrin antibodies negative group (21.6 months); however, this result does not reach statistical significance (P=0.09) (Figure 2B).

Figure 2 from Watts et al. JASN 2022: Kaplan-Meier curves for time to complete remission (A) and relapse-free period (B)

While the samples from the NEPTUNE database allowed the authors to analyze serum samples for anti-nephrin antibodies, they did not have access to kidney biopsy samples for these patients. The authors identified cases of MCD from their institutions in which they observed the punctate IgG positive staining pattern (MCD+) and compared them to biopsies that did not have the punctate staining pattern (MCD-). This punctate staining pattern for IgG is not thought to be an artifact of non-specific protein reabsorption as there is no colocalization of albumin (Figure 3).

Figure 3 (partial) from Watts et al. JASN 2022

Using high-resolution microscopy techniques, the authors found that IgG deposits colocalized with slit-diaphragm-associated nephrin in MCD+ samples, but not in MCD- biopsy samples (Figure 4A). This seemed to be a nephrin-specific colocalization; IgG did not colocalize with foot-process-associated synaptopodin (Figure 4B).

Figure 4 (partial, modified) from Watts et al. JASN 2022: Example confocal microscopy images from IgG-positive MCD (MCD# +) and IgG-negative MCD (MCD# -). The right panel is an enlargement of the boxed area in the corresponding left panel. Colocalization of IgG and nephrin is indicated by yellow luminescence (white arrows) in the MCD+ samples but not MCD- samples. There is clear spatial separation of IgG and synaptopodin staining (orange arrows).

The authors then validated their anti-nephrin antibody test on serum samples from patients whose biopsies they reviewed. Serum samples were available for 9 patients with MCD+ pathology, and all 9 were positive for the anti-nephrin antibodies. Zero out of 12 control samples (serum samples taken from patients with a variety of kidney disease pathologies) tested positive for anti-nephrin antibodies (Figure 5A, P=<0.001). Four MCD+ patients’ serum samples taken after treatment were available for anti-nephrin antibody testing, and, as in the post-treatment NEPTUNE samples, anti-nephrin antibodies could no longer be detected (Figure 5B).

Figure 5 from Watts et al. JASN 2022: Anti-nephrin antibody levels detected (A) and comparison of anti-nephrin antibody levels in active disease vs. remission (B).

As expected, biopsy samples from patients with nephrotic syndrome from membranous nephropathy and diabetic nephropathy did not show IF colocalization of IgG with nephrin on confocal microscopy (Figure S4).

Figure S4 (partial) from Watts et al. JASN 2022: Example confocal microscopy images from IgG-positive MCD (MCD# +), membranous nephropathy (MN1), and diabetic nephropathy (DN1). The right panel is an enlargement of the boxed area in the corresponding left panel. Colocalization of IgG and nephrin is indicated by yellow luminescence (white arrows) in the MCD+ samples but not MN or DN samples.

The authors also highlight a case of post-transplant nephrotic range proteinuria in a patient found to have high pre-transplant anti-nephrin antibody titer. The patient’s native kidney disease was caused by childhood-onset (but non-congenital), steroid-dependent MCD; 2 of the patient’s 4 native kidney biopsies showed an MCD+ staining pattern. Massive proteinuria occurred within days after transplant and responded to plasmapheresis and rituximab (Figure 6A). Although this case is consistent with an anti-nephrin antibody mediated MCD in the transplant kidney, the authors do not provide a description of a biopsy of the transplanted kidney.

Figure 6A from Watts et al. JASN 2022: (A) (B) (C)

Discussion

This study reports the first identification of anti-nephrin antibodies in patients with non-congenital minimal change disease, and it demonstrates a correlation between the presence of these antibodies and MCD disease activity. These findings identify at least one of the long sought-after circulating factors thought to cause the glomerular podocyte changes responsible for the nephrotic syndrome.

Clouding the picture had been the prevailing conclusion that, unlike other glomerular diseases, MCD has an absence of humoral (IgG and complement) deposition in the glomeruli. The authors focus on the slight granular pattern of IgG immunofluorescence staining seen in some patients with MCD, and suggest that this represents the in situ binding of anti-nephrin antibodies to their nephrin antigen(s). Furthermore, they speculate that this targeted nephrin binding may be sufficient to disrupt slit-diaphragm integrity and lead to the podocyte effacement that is characteristic of MCD.

This discovery highlights the heterogeneity of MCD and paves the way for new classifications or sub-types within NS and MCD. Nephrin is but one of the podocyte slit-diaphragm structural components; it is likely that other autoantibodies or circulating factors may also result in MCD-like glomerular disruption. Perhaps, like in membranous nephropathy, we are on the road to identifying more culprit antigens and potential treatment targets for minimal change disease. The prognostic significance of the presence of anti-nephrin autoantibodies remains to be seen, as there may be differences in long-term outcomes for nephrin-antibody positive vs negative MCD. But, these findings do provide a possible mechanistic explanation for the response of some patients to anti-B-cell therapy. Future studies should delve into whether anti-nephrin antibodies have utility for MCD diagnosis (perhaps when biopsy is not possible), can be used in treatment monitoring and/or prognosis, or have a role in pre-transplant evaluation.

Summary prepared by Jade Teakell, MD, PhD

Assistant Professor and Associate Program Director

Division of Renal Diseases and Hypertension,

McGovern Medical School, Houston, TX

NSMC Graduate 2021