#NephJC Chat

Tuesday, January 27th, 2026, 9 pm Eastern on Bluesky

N Engl J Med. 2025 Nov 20;393(20):1979-1989. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2509542. Epub 2025 Aug 29.

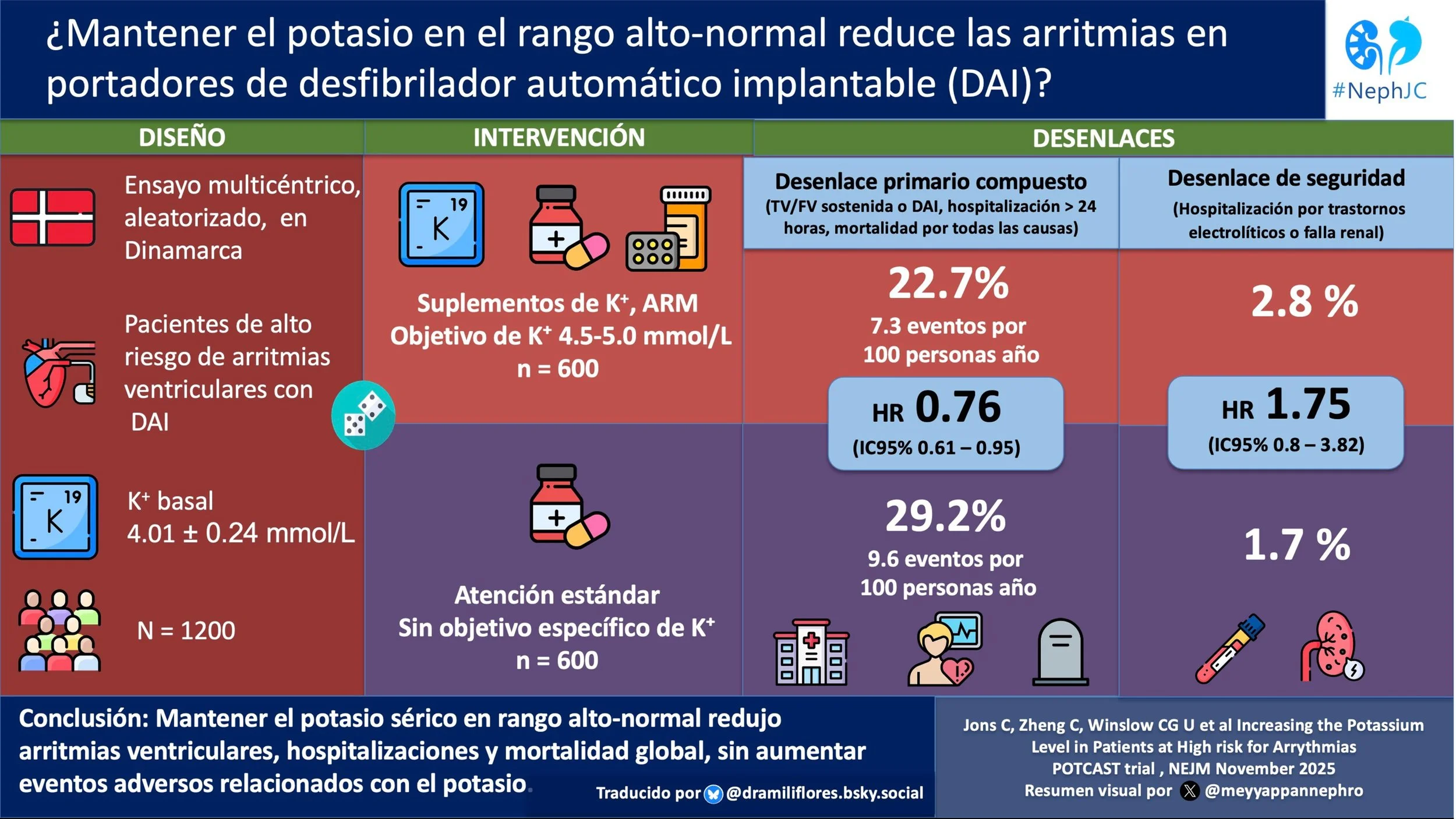

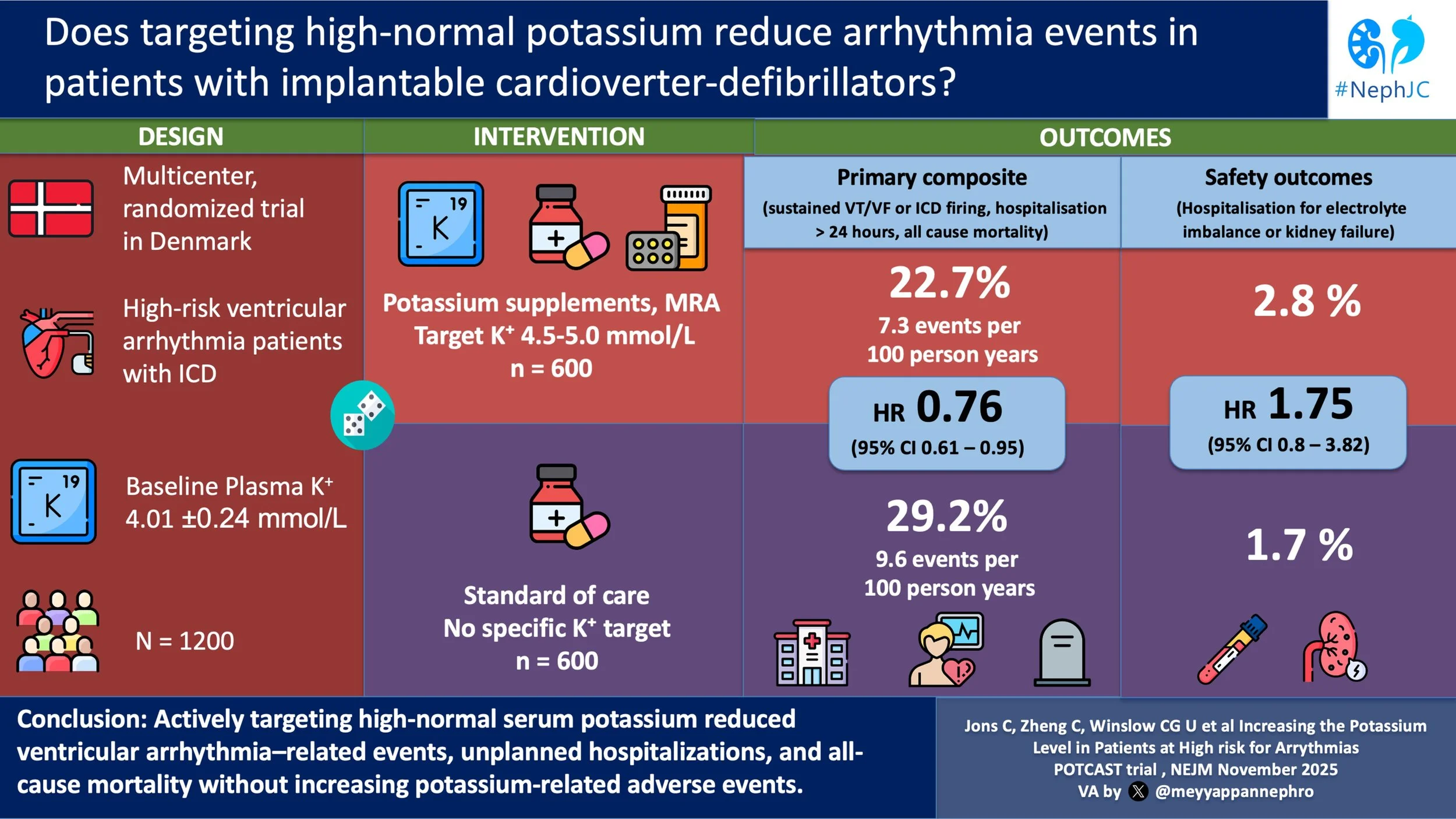

Increasing the Potassium Level in Patients at High Risk for Ventricular Arrhythmias

Christian Jøns, Chaoqun Zheng, Ulrik C G Winsløw, Elisabeth M Danielsen, Tharsika Sakthivel, Emil A Frandsen, Hillah Saffi, Sadjedeh S Vakilzadeh-Hashemi, Ketil J Haugan, Niels E Bruun, Kasper K Iversen, Helle S Bosselmann, Niels Risum, Henning Bundgaard; POTCAST Study Group

PMID: 40879429

Introduction

Hyperkalemia is flagged, paged, and protocolized - while hypokalemia often receives far less attention, as long as it remains within range. However, more and more data suggest that this lopsided angst may be detrimental. In patients with chronic heart failure, the relationship between potassium and mortality outcomes shows a U-shaped relationship. Observational data suggest that hypokalemia has a similar association with increased 60-day all-cause mortality as hyperkalemia. More strikingly, even potassium levels traditionally considered low-normal (3.5–4.0 mmol/L) appear to carry some risk. In contrast, potassium concentrations in the high-normal range of 4.5–5.0 mmol/L are associated with the lowest mortality. (Jønsson et al. Eur J Intern Med, 2023)

Figure 4. Standardized 60-day absolute risk of all-cause mortality. From Jønsson et al, Eur J Intern Med, 2023

Mechanistically, this makes sense. Hypokalemia reduces key repolarizing potassium currents and Na-K-ATPase activity, causing intracellular Na and Ca loading, CaMK activation, and a fertile substrate for early and delayed after-depolarizations, polymorphic VT, and VF. Hyperkalemia, for its part, depolarizes the resting membrane, shortens action potential duration, and slows conduction, predisposing to heart block and VF once levels are sufficiently high. (Weiss et al, Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol, 2017)

Cardiovascular disease is the dominant cause of death in patients with CKD and ESRD, accounting for up to 50% of mortality. (Stevens et al. Kid Int, 2007) At the same time, many of the therapies we prescribe for kidney protection: diuretics, renin–angiotensin system inhibitors, and mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists, alter potassium homeostasis. While cardiologists often aim for “normal” potassium (4.0 mmol/L), nephrologists often like to have a little room for dietary indiscretion. Notably, two pillars of both cardiology and nephrology CKD care, RASi (ACE inhibitors/ARBs) and mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists (MRAs), have been shown in studies to decrease mortality, including sudden cardiac death. (Domanski et al. J Am Coll Cardiol, 1999 and Solomon et al. Circulation, 2004) While these benefits are undoubtedly multifactorial, it is tempting to ask whether the accompanying rise in serum potassium is a key contributing mechanism.

More evidence in favor of potassium supplementation in patients with normal serum potassium levels comes out of China, where they completed a cluster-randomized trial with 600 villages (SSaSS Study| NephJC). A potassium-based salt substitute was administered, leading to a reduced rate of major cardiovascular events and stroke. (Neal et al. NEJM, 2021) The additional positive effect on blood pressure has even led to an inclusion in both the most recent American and European hypertension guidelines. It is unclear if decreased sodium or increased potassium intake was responsible for the findings.

So, a higher serum potassium and increased potassium in the diet may benefit certain populations. The question remains, is it OK to aim for a higher K+ in patients at risk for arrhythmia?

The Study

Methods

Study Design

POTCAST was an investigator-initiated, event-driven, open-label, 1:1 randomized, superiority trial. It was conducted in three ICD-implanting centers in Denmark.

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion criteria

Adults 18 years of age and older who had an ICD or a cardiac resynchronization therapy defibrillator and had a baseline plasma potassium level of 4.3 mmol/L or lower.

Exclusion criteria:

eGFR < 30 ml/min/1.73 m2 or pregnant.

Randomization

Participants were randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio to the ‘high-normal’ potassium group or standard of care. Randomization was computer-generated. There was no blinding of participants or treating clinicians.

Interventions

The high-normal potassium group aimed to achieve a plasma K of 4.5-5 mmoL/L. The components of the intervention were:

Written dietary counseling promoting potassium-rich diet

Mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist (max dose 100 mg for spironolactone or 50 mg for eplerenone, somewhat odd as eplerenone is less potent than spironolactone)

Oral potassium supplementation using potassium chloride 10 mmol tablets (max dose 4.5 g or ~60 mmol)

Reduction or discontinuation of loop or thiazide diuretics when possible.

Titration:

Visits every 2 weeks during the adjustment phase with measurement of potassium, creatinine, and blood pressure

Dose adjustments were based on potassium level, kidney function, blood pressure, and tolerance

Maintenance:

After stabilization, follow up every 6 months.

Treatment adjustment was done only if K >5 mmoL/L, or unacceptable side effects.

The standard of care group received guideline-directed medical therapy for the underlying cardiac condition. There was no protocol K supplementation or K target. The follow-up was biannual, with laboratory measurements identical to those of the intervention group.

Patients were followed from the point of randomization until the end of the trial (March 25, 2025) or upon study withdrawal or death.

The primary endpoint

Time-to-first event was a composite of:

Sustained ventricular tachycardia with a rate > 125 bpm lasting more than 30 seconds documented by ECG or ICD

Appropriate ICD therapy documented via ECG or ICD (e.g. any necessary shocks delivered)

Unplanned hospitalization for more than 24 hours for arrhythmia or heart failure which led to a change in medications or resulted in invasive treatment

Death from any cause during the trial period

Key secondary endpoints

Death from any cause

Hospitalization for heart failure, cardiac arrhythmias, kidney failure or electrolyte disturbances, or supraventricular arrhythmias

Any appropriate ICD therapy

Any inappropriate ICD therapy (in the absence of arrhythmia)

Safety outcomes

Hypokalemia and hyperkalemia (referred to ER for management if >6 mmol/L)

Changes in plasma creatinine levels

Hospitalization for other cardiovascular causes, noncardiovascular causes, or any cause

Composite of hospitalization for any cause or death

Statistical methods

It was assumed that increasing potassium levels to 4.5 - 5.0 mmol/L would result in fewer primary outcome events. It was also assumed that only 70% of participants randomized to the high-normal group would reach target potassium levels. Based on this, the trial was designed to have 80% power to detect a 28% lower risk of the primary end-point in the high-normal potassium group compared to the standard of care group. The assumption was also for ~ 16% event rate annually with standard care (and 11.5% in intervention). This required 291 events which resulted in the need to expand the initial projected enrollment number of 1000 to 1200 in the second half of the trial due to a lower than anticipated event rate. Time-to-first-event methods were used to analyze the primary endpoint in the intention-to-treat population. A Cox proportional-hazards model was used to assess for differences in risks between the groups. A two-sided P value of less than 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. No multiplicity correction was done beyond the primary endpoint.

Funding

The trial was funded by grants from the Independent Research Fund Denmark, the Danish Heart Foundation, and the Novo Nordisk Foundation. There is no clear link between Novo Nordisk products and the nature of this research. so there is no obvious evidence of potential funding bias.

Results

A total of 600 participants were randomized to the standard care group and 600 to the high-normal potassium group. Median follow-up was 39.6 months.

Figure S1. Consort diagram, from Jøns et al NEJM, 2025

Baseline characteristics can be seen in table below. Notably, at baseline, the mean plasma potassium level in both groups was 4.01 mmol/L. Additional details provided in the supplement reveal that ‘Kidney Failure’ was present in 10% of controls and 11% in the high-normal potassium group (definition not provided but we know they were stage G2-G3b given that eGFR < 30 ml/min/1.73m2 was an exclusion criteria) and 71% of both groups were taking an ACEi/ARB/ARNI at baseline.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics, from Jøns et al NEJM, 2025

Figure S2. Distribution of plasma potassium levels at baseline (blue bars) and at the end of the uptitration period (red bars) in the high-normal potassium group, from Jøns et al NEJM, 2025

Among the 572 in the high-normal potassium who completed the medication/supplement adjustment period (which lasted a median of 85 days), there was a mix of MRA use, potassium supplement use, both, or neither (Table S2).

Table S2. Categories of treatment groups in high-normal potassium group, from Jøns et al NEJM, 2025

Potassium Target Achievement

Only 41.5% (249 participants) of the original 600 randomized to the nigh-normal potassium group reached the target potassium level of 4.5 - 5.0 mmol/L (versus the 70% anticipated). Reasons for not meeting the target included reaching the maximum tolerated dose (146 participants), declining more medications (71 participants), reaching the maximum dose of the supplement/MRA allowed by the protocol (52 participants ), or other reasons (54 participants ).

Potassium levels increased from a mean of 4.01 mmol/L at baseline to 4.36 mmol/L after the dose adjustment period in the high-normal potassium group, as compared with an increase from a mean of 4.01 mmol/L at baseline to 4.05 mmol/L after 6 months in the standard care group.

Treatment Adherence

There were 67 participants in the high-normal potassium group who discontinued study medications at some point in the trial due to medication-related side effects (27% related to an MRA, 34% related to potassium supplements and 39% related to both). See the specific side effects reported below. (Table S3b)

Table SB2. Treatment side effects, from Jøns et al NEJM, 2025

Efficacy outcomes

Primary endpoint

The primary endpoint occurred in 22.7% of the high-normal potassium group participants, or 7.3 per 100 person-year. In the standard care group, 29.2% had a primary endpoint event, or 9.6 person-years. The difference was statistically significant, with a HR of 0.76 (CI 0.61 to 0.95; p = 0.01). Thus they observed a total of 311 events (versus 291 needed) with a 24% RR reduction - slightly lower than the expected 28%, but still pretty close, despite the lower proportion who achieved target potassium levels. When looking at the individual components of the composite outcome, the finding was driven primarily by a reduction in necessary ICD firing/ventricular tachycardia and hospitalization for cardiac arrhythmia. (Figure 1)

Figure 1A. Primary endpoint, from Jøns et al NEJM, 2025

Similar hazard ratios were seen when looking separately at those who received an MRA (HR 0.75, 0.58 to 0.97) and those who did not (HR 0.77, 0.56 to 1.00) and when looking at those who reached the target potassium level (n = 249; HR 0.84, 0.63 to 1.12) and those who did not (n = 351; HR 0.70, 0.53 to 0.92).

Secondary endpoints

Hospitalization for supraventricular arrhythmias was reduced in the high-normal potassium group compared to the standard-care group, while there was no difference between the groups for hospitalization for electrolyte abnormalities or kidney failure, ventricular arrhythmias or frequency of inappropriate ICD therapy. (Table 2)

Table 2. Primary, secondary, and safety endpoints, from Jøns et al NEJM, 2025

Safety endpoints

There were no differences between the groups for safety outcomes including hospitalization for other cardiovascular causes, non-cardiovascular causes, any cause or death (Table 2), apart from the side effects discussed above. Serum creatinine levels were higher in the high-normal potassium group, but only slightly (~0.1 - 0.2 µmol/L).

Discussion

Potassium has an atomic number of 19, but it is number one in most nephrologists’ hearts. Cardiac myocytes rely on a negative resting membrane potential to remain electrically stable between beats. The high intracellular concentration of potassium relative to the outside of the cell is the main determinant of this resting potential because K tends to diffuse out of the cell through potassium channels, leaving behind a negative charge inside. This gradient is maintained by the Na-K-ATPase pump. Without an appropriate potassium gradient (The Goldilocks Zone: not too high or too low), the cardiac cells can become more excitable and unstable, increasing the likelihood of aberrant electrical impulses. Cardiac potassium currents are the primary drivers of repolarization. They return the membrane potential toward baseline after each beat, allowing the heart to be ready for the next impulse. If K⁺ currents are reduced or dysfunctional, repolarization is delayed, increasing susceptibility to re-entrant circuits and early depolarizations. At least in observational studies, low serum potassium raises the risk of arrhythmias, including atrial fibrillation and life-threatening ventricular arrhythmias. Hypokalemia can prolong the action potential duration and increase myocardial excitability. (Podrid PJ. Am J Cardiol,1990) In addition, as we were all drilled as interns, hyperkalemia similarly can lead to prolongation of the QRS complex, slowing ventricular depolarization, and impairing cardiac conduction leading to ventricular fibrillation and asystole.

We have previously discussed these risks specifically in dialysis patients (ADAPT| NephJC). The ADAPT trial- a prospective, randomised, open-label crossover study- looked at the use of higher potassium baths (3.0 K+) in conjunction with potassium binding medications and the risk of arrhythmias in patients on hemodialysis. (Charytan et al. Kid Int, 2025) The hypothesis was that inter/intradialytic potassium homeostasis could be maintained and potassium flux minimized. Utilizing higher concentrations of dialysate potassium appeared to be an effective approach, when combined with intestinal potassium binders, to mitigate the risk of intra and post-dialytic hyperkalemia. The study concluded that at least in ESRD patients, preventing hypokalemia and greater potassium variability appeared to decrease the incidence of atrial fibrillation and “clinically significant cardiac arrhythmias”. However, following the ADAPT trial the subsequent DIALIZE-Outcomes trial, using the potassium binder sodium zirconium cyclosilicate in hemodialysis, failed to show similar arrhythmia benefits in dialysis patients despite serum potassium control. The DIALIZE trial did not use higher potassium baths and was stopped early due to a low event rate (Fishbane et al. Kid Int 2025)

The bigger issue in CKD, and non-dialysis patients in general, is how to maintain a serum potassium within a narrow therapeutic window? Medications and associated hypotension, CKD stage, diet and cellular shifts make this somewhat impractical in the clinical setting. Even in a study setting, the authors were unsuccessful at getting >50% of patients to a potassium target of 4.5-5 mmol/L. In a non-study clinical setting, without frequent point-of-care monitoring, this task seems daunting if not impossible. In addition, patient compliance with treatments to elevate potassium levels is an issue. It is important to note that even in this trial population, approximately 12% of patients declined taking more medication, or reached the maximum tolerated dose without reaching the potassium target. If we agree that high normal or even moderately elevated potassium levels are beneficial for patients at increased risk of arrhythmia, this study highlights the significant challenges of achieving and maintaining a patient's potassium at that goal. Finally, there were no safety differences between the groups, however, it was not reported how many patients (in either group) were referred to the emergency department for potassium management. The study only reports that there were ten “electrolyte or renal failure episodes” in the control group and seventeen in the high-potassium group leading to hospitalization for hyperkalemia or hypokalemia, about 1% of both groups. If we were to push the envelope of potassium supplementation, one would expect many more complications related to hyperkalemia (and perhaps they were managed in the ER and discharged?). In the end, there was only a 0.3 mmol/L difference in potassium levels between treatment and control patients, yet arrhythmia and hospitalization outcomes were better in the treatment group.

The benefits seen in this study occurred across all cardiovascular disease types and regardless of the method used (e.g., potassium supplementation or MRAs). The increased potassium seen with MRAs may not just be a simple side-effect, but may also be partly responsible for better outcomes for patients taking MRAs. Previous studies of non-potassium sparing diuretics in hypertensive patients suggest a higher incidence of hypokalemia and sudden cardiac death. (Hoes, et al. Drugs, 1994) There is a surprising lack of data comparing sudden cardiac death and arrhythmia in patients on potassium sparing versus non-potassium sparing diuretics. As for MRAs they have shown significant benefits over a series of studies spanning decades. The RALES trial showed a 30% reduction of death versus placebo in patients with severe heart failure. (Pitt et al. NEJM, 1999) Furthermore, in EPHESUS, eplerenone decreased the risk of CV mortality by 32% and sudden cardiac death by 37% following acute MI. (Pitt et al. J Am Coll Cardiol, 2005) Finally, in FIDELITY, finerenone lowered the incidence of sudden cardiac death by 25% in patients with type 2 diabetes and CKD. (Filippatos et al. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Pharmacother, 2023) One must seriously question, however, if the findings in POTCAST are really that different from other trials involving MRA/nsMRAs. This study does not separate the systemic effects of MRAs from high-normal potassium, however 30% of patients did not receive an MRA at all.

If arrhythmia is the question and potassium is the answer, particularly in high risk populations, then perhaps we should be redefining the upper and lower limits of potassium to increase awareness.

On the other hand, patients with significant CKD and ESRD, who are predisposed to hyperkalemia, do not seem to reap the benefits of elevated potassium on CV disease and sudden cardiac death. This is just one more study, from evidence gleaned from observations more than thirty years ago, to support the use of MRAs and potassium supplementation (in lew of sodium chloride) in patients who can tolerate them and are willing to be subjected to frequent monitoring.

Strengths of the study

Recruitment was strong and allowed for enough participants to achieve power. Any event that was classified as a potential component of the composite primary end point was adjudicated by an external adjudication committee, which adds validity to the findings.

Limitations of the study

The trial was only performed in one country, so generalizability to diverse populations is limited. The study included only patients with ICDs, so the results cannot be extrapolated to other patients with high CV risk. Important to our nephrology community, the trial excluded patients with eGFR < 30, which is disappointing given that this particular group of patients has the highest CV risk and may stand to gain the most if found to benefit. One of the main limitations is the difficulty in sorting out possible beneficial CV-related MRA effects unrelated to their potassium elevating effects. While hazard ratios within the high-normal potassium group were reported separately for those taking MRAs and those not, the study was not designed to investigate differences in impact of MRAs versus potassium supplements, so we can’t be sure that we aren’t seeing the impact of MRAs on the primary outcome rather than the impact of targeting a high-normal potassium level. Finally, less than half of participants reached the potassium target.

Conclusion

In this multicenter open-label study, patients with ICDs and mild to moderate CKD had fewer arrhythmias and cardiovascular hospitalizations when aiming for a potassium in the high-normal range. Generalizability of this study is limited by the specific characteristics of the studied participants and failure of the study to reach its planned potassium goal.

Summary by

Shellie Fravel, PharmD

Iowa City, IA

Clemens Weber, MD

University Hospital Mainz, Germany

Reviewed by

Milagros Flores, Brian Rifkin,

Joel Topf, Cristina Popa