#NephJC chat on March 15th 9 pm Eastern

March 16th 8 pm GMT, 4 pm Eastern and 1 pm Pacific

JAMA Intern Med. 2016 Feb 1;176(2):238-46. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.7193.

Proton Pump Inhibitor Use and the Risk of Chronic Kidney Disease.

Lazarus B, Chen Y, Wilson FP, Sang Y, Chang AR, Coresh J, Grams ME.

Toll free link courtesy of JAMA click here (will work until March 17th).

Summary below, also review this Renal Fellow Network blog post from Praveen Malavade and the editorial in JAMA

Pre-Chat Summary

Proton pump inhibitors (PPI) were first available by prescription in 1989 and represent one of the most widely prescribed medications worldwide (1). Their availability increased in 2003 after being approved by the Food and Drugs Administration (FDA) for ‘over-the-counter’ use (2). They are the most cost-effective treatment for GERD (3). PPIs act by binding to the H+/K+ ATPase pump on gastric parietal cells, reducing acid secretion into the gastro-intestinal tract (1).

There are increasing concerns regarding the long-term safety of PPIs (4). These relate to a potential increased risk of pneumonia, bone fractures and enteric infections (5). There is also anxiety regarding a possible interaction with clopidogrel (with a reduction in its anti-platelet effects), as well as reports of PPI-induced acute kidney injury (AKI), biopsy-proven acute interstitial nephritis (AIN), hyponatremia and hypomagesemia (1, 5, 6). To date, the FDA provides four PPI-specific alerts (7).

The subject of this week’s #NephJC is an article that tackles another PPI-related safety concern: a potential association between chronic kidney disease (CKD) and PPI use (8).

Methods

Study Design

This is an observational, prospective cohort study with two cohorts. The first is the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study, of which 10,482 participants were included. The second was the much larger Geisinger Health System Replication (GHSR) Cohort, with 248,751 participants.

Clinical outcomes and variables

ARIC cohort

Participants were followed-up through an annual telephone survey.

CKD and AKI were defined using diagnostic codes.

Details regarding prescribed medication were obtained at the baseline visit.

Information about ongoing or new PPI use was obtained through the telephone survey from 2006.

GHSR cohort

CKD was defined on the basis of a new eGFR result of <60ml/min/1.73m2.

Prescribed medication were obtained at the baseline visit.

Statistical analysis

The hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals used to estimate risk of CKD were calculated using cox proportional hazards regression.

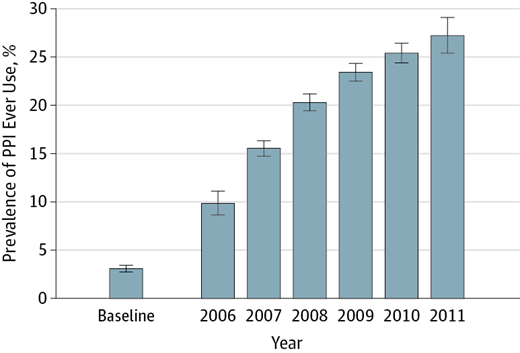

After PPI use was identified, it was assumed the participant was a permanent PPI user at all times thereafter (Fig. 1).

Figure 1 from Lazarus et al, JAMA 2016

Important sensitivity analyses:

Participants using either PPIs or H2 antagonists were compared with each other to evaluate their respective risk of developing kidney disease.

A propensity score-matched analysis was conducted to minimise confounding variables and identify whether baseline PPI use was associated with CKD.

Key results

PPI users in both cohorts were more likely to have a high BMI, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, and exhibit polypharmacy (with antihypertensives, aspirin, diuretics and statins).

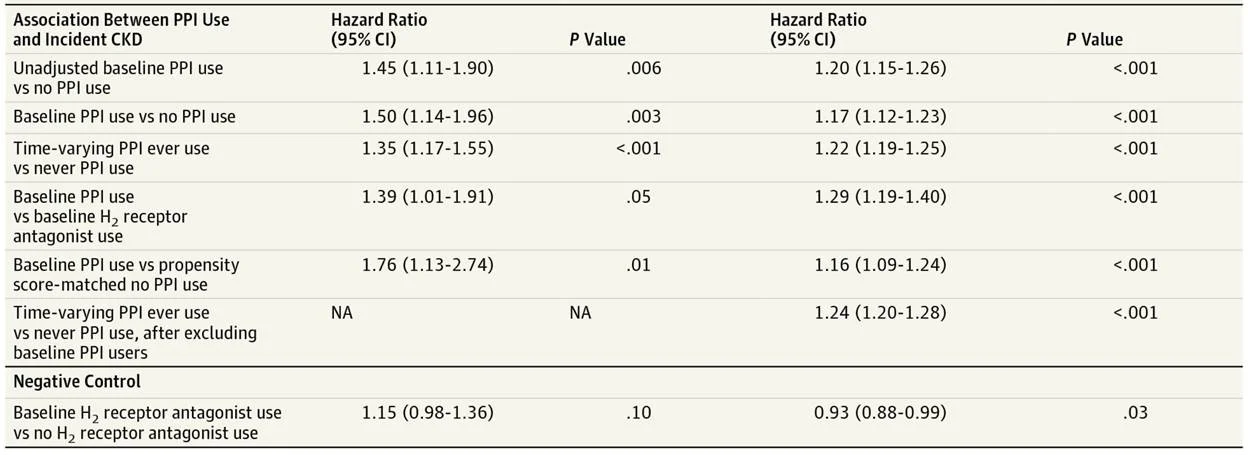

Table 2 from Lazarus et al, JAMA 2016

Similar findings were obtained for AKI

In the GHSR cohort, twice-daily PPI use was associated with an even greater risk of CKD (adjusted HR 1.46, 1.28-1.67) than once-daily schedules (adjusted HR 1.15, 1.09-1.21), suggesting a dose-dependent adverse effect

Discussion points

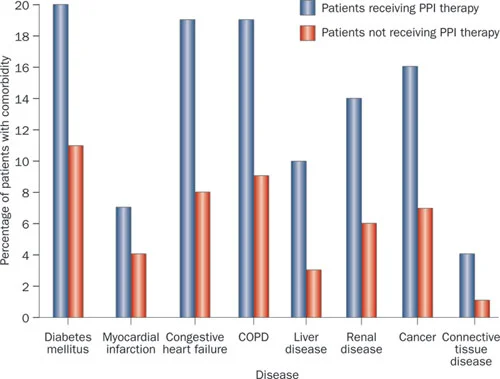

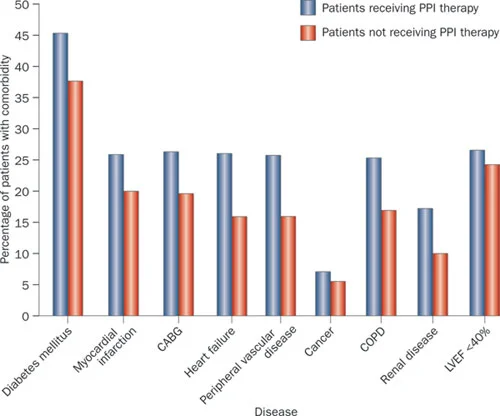

Co-morbidities: PPI users are consistently identified as having a greater burden of co-morbidity than non-PPI users. This is true in this study and in others (Figs.2&3) (5).

Fig 2 from Moayyedi et al, used with permission

Those given PPI therapy have more concurrent medical problems than those not prescribed these drugs.

Fig 3 from Moayyedi et al, used with permission

Those given PPI therapy had more concurrent medical problems than those not prescribed these drugs.

Observational studies vs. RCT: there remains a significant risk of residual bias in this study, even after correction for confounding variables.

The magnitude of residual bias in observational studies has now been identified as significant and likely to account for the ‘harmful’ effects supposedly observed in PPI users suffering bone fractures (9). Further discrediting a potential harmful effect of PPIs on bone, Itoh et al published the results of an RCT in 2013 (10). 180 women with low bone mineral density (BMD) were randomised to either ‘bisphosphonate-only’ or ‘bisphosphonate plus PPI’. After 9 months, the ‘bisphosphonate plus PPI’ group had significantly increased BMD compared to the ‘bisphosphonate-only’ group.

If we were to apply the above rationale to the other proposed adverse effects of PPIs, how would this change our interpretation of the evidence? (see Table below)

Table from editorial, by Schoenfield and Grady, JAMA 2016

Over-the-counter medications: Participants had easy access to common medications including NSAIDs, which are often associated with interstitial nephritis. This study was also unable to assess over-the-counter PPI use, and thus the potential exposure to PPIs in both groups may be underestimated.

Clinical data: what effect has the use of diagnostic codes rather than laboratory data had on this study’s results?

What is the mechanism for incident CKD in PPI users?

o Recurrent AKI or subacute AIN?

o Hypomagnesaemia?

My take

Whilst the size of the adverse effect observed in this large study is a concern, I do not believe we can justifiably change our practice and warn against the use of PPIs. There are enough biopsy-proven cases of PPI-induced AIN in the literature for me to accept PPI use as a (rare) cause of AKI. However, there simply remains too great a risk of significant residual bias in the present study for conclusions to be made about an association with CKD. Nonetheless, Lazarus et al do help us acknowledge a key point: that we are prescribing too many PPIs without due clinical indication.

Summary written by Peter Gallacher, Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh

#NephJC chat on March 15th 9 pm Eastern

March 16th 8 pm GMT, 3 pm Eastern and 12 noon Pacific