N Engl J Med. 2025 Nov 20;393(20):1990-2000. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2508157. Epub 2025 Aug 29.

Reduction of Antihypertensive Treatment in Nursing Home Residents

Athanase Benetos, Sylvie Gautier, Anne Freminet, Alice Metz, Carlos Labat, Ioannis Georgiopoulos, François Bertin-Hugault, Jean-Baptiste Beuscart, Olivier Hanon, Patrick Karcher, Patrick Manckoundia, Jean-Luc Novella, Abdourahmane Diallo, Eric Vicaut, Patrick Rossignol; RETREAT-FRAIL Study Group

PMID: 40879421

Why was this study done?

Goals for patients with hypertension have been extensively explored in the last decade. Studies including SPRINT, BPROAD, and ESPRIT have shown the MACE benefits of decreasing blood pressure to “near normal” values in a wide range of patients with varied comorbidities. However, all of these studies had a mean age below 70 years and excluded patients living in nursing homes. Though there was a benefit of intensive BP lowering in these patients who were older, even when analysed by frailty (e.g. Wang et al Circulation 2023), inherently these patients included in trials were not very ‘frail’. Standing BP < 110 and living in a nursing home were exclusions - and in those patients there exists an important evidence gap. We do know that blood pressure declines in the last few years before death, when viewed through a retroscope (Delgado et al, JAMA IM 2018).

Figure 1 from Delgado et al, JAMA IM 2018 Estimated Mean Systolic Blood Pressure (SBP) in the 20 Years Prior to Death, by Age at Death (60-69, 70-79, 80-89, ≥90 Years)

This is not entirely surprising - after all it would not be unusual that BP would go down with heart failure, advanced cancer and malnutrition, infections etc. This does make it a good opportunity to deprescribe BP lowering drugs - if not anything else, to at least reduce pill burden and polypharmacy, and possibly reduce risk of hypotension, falls, and syncope. There have been some attempts at deprescribing trials. OPTIMISE was a 12 week trial which included > 80 year old patients from primary care with BP < 150 mm Hg and on 2 or more BP lowering drugs (Sheppard et al JAMA 2020). Participants were enrolled to getting one drug deprescribed, with an outcome of having SBP remain < 150 mm Hg at 12 weeks. This was a non-inferiority design with a margin of 0.90, and the trial did report non-inferiority (adjusted RR, 0.98 [97.5% 1-sided CI, 0.92 to ∞]). But medication reduction was only sustained in 2/3rds of the participants at 12 weeks, and mean change in SBP was 3.4 mm Hg higher in the intervention group. The serious adverse events were not significant (4.3% participants in the intervention group and 2.4% in the control group) though this was admittedly too short a follow up period. Would that 3.4 mm Hg higher SBP translate into a worse CV outcome profile over a longer time? We do not want to reduce pill burden and hasten a few extra strokes at the end of life.

So, in octogenarians with hypertension, what are the risks and benefits of discontinuing anti-hypertensive medications? Does individualizing blood pressure management, and allowing for higher blood pressure targets as suggested by guidelines, lead to decreased morbidity and mortality?

Table 1. Comparing 2017 AHA/ACC guidelines (Whelton et al Hypertension 2017) with 2023 ESH Guidelines (Mancia et. al J. Hypertens. 2023) and the 2024 ESC guidelines (McEvoy et al EHJ 2024)

How was the trial done, and what did it show?

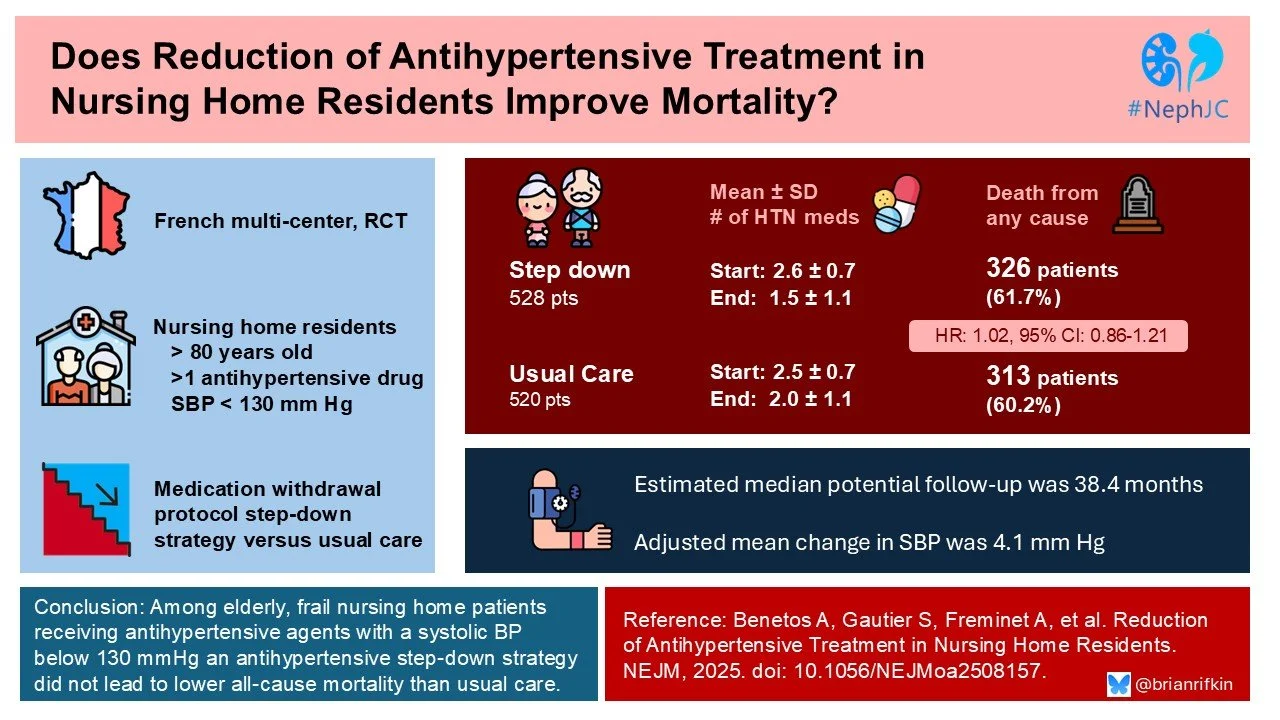

RETREAT-FRAIL (Reduction of Antihypertensive Treatment in Frail Patients) was a pragmatic, interventional, randomized trial that evaluated the effect of a protocol-driven strategy of progressive reduction of antihypertensive therapies as compared with usual care on all-cause mortality. The study included nursing home residents who were 80 years of age or older and had frailty, had a systolic blood pressure of less than 130 mm Hg, and were receiving at least two anti-hypertensive agents.

Methods

The study participants included patients in 108 nursing homes in France. A coordinating team provided online training regarding standardized blood-pressure measurements to the physicians caring for patients enrolled in the trial. Patients were randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio to a protocol-driven strategy of progressive discontinuation of anti-hypertensive drugs (step-down group) or usual care (control group). Follow-up was for up to 4 years after enrollment. Patients underwent a complete clinical evaluation, which included assessment of Activities of Daily Living, Mini–Mental State Examination, muscular force with a hand-grip strength test, mobility with a walk test, and the Short Physical Performance Battery. Assessment of quality of life was accomplished with the European Quality of Life 5-Dimension 3-Level (EQ-5D-3L) questionnaire. The level of frailty was assessed with an algorithm that calculated a composite score.

The protocol-driven reduction of anti-hypertensive medications began immediately after randomization in all the patients in the step-down group. Subsequent discontinuation of treatments occurred during visits at 3 and 6 months and then every 6 months thereafter if the systolic blood pressure remained below 130 mm Hg in the absence of an acute medical illness. Only one medication could be discontinued at each visit. In the case of beta-blockers, treatment was first reduced to a half dose and then withdrawn 1 week later if the systolic blood pressure remained below 130 mm Hg; the same approach was used with loop diuretics unless these drugs were being used at low doses. All other drugs were discontinued without a reduction in dose. If the patient’s systolic blood pressure increased to 160 mm Hg or greater after treatment reduction, treatment with the last discontinued drug was reintroduced at a half dose.

Figure S2. Protocol for reintroduction of medication in patients of the intervention group presenting systolic blood pressure (SBP) ≥160 mmHg after drug reduction. Benetos A, et al. NEJM 2025.

End points

The primary end point was death from any cause. The assumption was that lowering BP meds would reduce mortality by a whopping 25% with a 30% event rate in the control group. This was based on an observational study (PARTAGE Benetos et al JAMA IM 2015) which reported ~ 80% higher mortality in those with low SBP and on BP lowering medications. This was a traditional superiority design, unlike the non-inferiority design of OPTIMISE. Secondary end points included a composite of major adverse cardiovascular events as assessed by an independent adjudication committee, death from noncardiovascular causes, the change from baseline in systolic and diastolic blood pressure, the change from baseline in functional capacity (the score on the ADL, the score on the SPPB, and the peak force on the hand-grip test) assessed as the area under the curve (AUC), the change from baseline in the score on the MMSE assessed as the AUC, the number of fractures, the number of falls, the change from baseline to the last trial visit in the total number of medications, the change from baseline to the last trial visit in the number of anti-hypertensive drugs, the change from baseline in the score on the EQ-5D-3L questionnaire as assessed as the AUC, and death from coronavirus disease 2019 (Covid-19).

Results

A total of 1048 residents from 108 nursing homes underwent randomization: 528 to the step-down group and 520 to the usual-care group. The patients underwent randomization from April 15, 2019 through July 1, 2022. Follow-up visits ended in July 2024, 24 months after the last patient had undergone randomization. The median follow-up was 38 months. The mean age of the patients was 90 years, and 81% were women. The mean systolic blood pressure was 113 mm Hg in the step-down group and 114 mm Hg in the usual-care group; the mean diastolic blood pressure was 65 mm Hg in both groups.

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics. Benetos A, et al. NEJM 2025.

At baseline, the mean number of anti-hypertensive medications being taken by the patients was 2.5, of which 1.8 were “list 1” medications (could potentially be discontinued) and 0.7 were “list 2” medications (could not be discontinued due to compelling indication).

Figure S1. Drug discontinue algorithm. Benetos A, et al. NEJM 2025.

Table 2. Baseline Medications. Benetos A, et al. NEJM 2025.

End points and safety

The adjusted mean between-group difference in the change in systolic blood pressure was 4.1 mm Hg (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.9 to 5.7); the adjusted mean between-group difference in the change in diastolic blood pressure was 1.8 mm Hg (95% CI, 0.5 to 3.0). Drug reintroduction because of an increase in systolic blood pressure to 160 mm Hg or higher occurred in 7 patients in the step-down group. The mean number of antihypertensive drugs (list 1 plus list 2) being used decreased from 2.6 at baseline to 1.5 at the last trial visit in the step-down group and from 2.5 to 2.0 in the usual-care group.

Figure S4. SBP over time, least square means. Benetos A, et al. NEJM 2025.

Death from any cause (primary end point) occurred in 326 patients (61.7%) in the step-down group and in 313 (60.2%) in the usual-care group (adjusted hazard ratio, 1.02; 95% CI, 0.86 to 1.21; P=0.78). Death from noncardiovascular causes occurred in 284 patients (53.8%) in the step-down group and in 278 (53.5%) in the usual-care group. An equal percentage of both groups (50%) experienced a fall. A fracture occurred in 41 patients (7.8%) in the step-down group and in 48 (9.2%) in the usual-care group.

A composite of major adverse cardiovascular events occurred in 102 patients (19.3%) in the step-down group and in 90 (17.3%) in the usual-care group (hazard ratio, 1.15; 95% CI, 0.84 to 1.56). Serious adverse events other than those included in definitions of the primary and secondary end points occurred in 132 patients in the step-down group and in 128 patients in the usual-care group and were generally similar in the two groups.

Table 3. Primary and secondary endpoints. Benetos A, et al. NEJM 2025.

What are the implications?

Like most guidelines that are based upon expert opinion and observational studies, it is always best to get additional RCT data if possible to reinforce “common sense” recommendations. Unfortunately, this study failed to show any significant differences in death, heart failure, MACE, falls or fractures for those randomized to less intense blood pressure control in a frail, elderly population. If we are to take this as a “glass half-full” scenario, it is at least reassuring that decreasing a patient’s pill burden had few negative consequences (and fewer medications means fewer potential drug-drug interactions). In the end, because this was a pragmatic trial, the overall number of medications only differed by 0.5 pills at last follow-up, and the adjusted mean square difference in systolic blood pressure was fairly small (4 mm Hg). The authors noted a decrease from baseline to the last follow-up visit in the mean number of antihypertensive medications being taken in the usual-care group. This finding suggests that physicians may routinely reduce hypertension treatments as patients become older and frailer, understandably out of caution. But this demonstrates that the study design was incorrect - to draw this conclusion (reducing BP medications does not cause harm) the authors should have undertaken a non-inferiority design and then clearly demonstrated non-inferiority (see NephJC stats post on non-inferiority). The 95% CI for the primary outcome was 0.86 to 1.21 for ITT and 0.87 to 1.23 for per protocol (which may be preferred in NI designs); with a non-inferiority margin of 15 or 20%, this trial would have failed the non-inferiority test (possibly because it may have underpowered for this result).

Figure S5. Number of anti-hypertensive drugs interrupted. Benetos A, et al. NEJM 2025.

Conclusion

Among elderly, frail nursing home residents, with well controlled hypertension (<130 mmHg), a step-down strategy of anti-hypertensive medications did not lead to a change in mortality.